This post is comprised of different sections

Take a look at our review of The Elephant Celebes!

Learn more about free-association and the Activation-Synthesis Theory!

This post is comprised of different sections

Take a look at our review of The Elephant Celebes!

Learn more about free-association and the Activation-Synthesis Theory!

Artist: Max Ernst

Year: 1921

Medium: Oil on canvas

Location: Tate Modern, London, UK

Dimensions: 125.4 cm x 107.9 cm

Original Title: Celebes

Our rating

Your rating

Although I consider myself an ardent fan of surrealism, I’m ashamed to admit I only came across Max Ernst’s works in a not so distant past.

And that is quite embarrassing.

After all, and despite lacking the fame of a Salvador Dali or Pablo Picasso, Max Ernst is indisputably a central figure in the surrealist movement.

In this article, I will analyse one of Ernst’s paintings which has become, arguably, the face of surrealistic art: The Elephant Celebes.

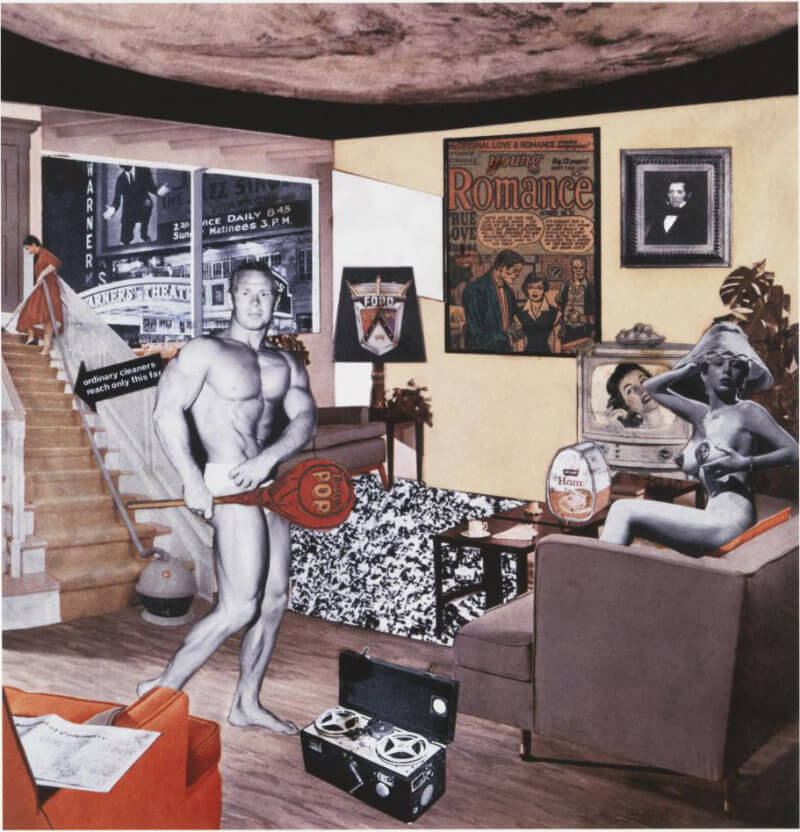

The Elephant Celebes was painted by German surrealist artist Max Ernst in 1921.

The composition is made up of several seemingly unrelated elements. The most obvious one is a central mechanical monster with an appendage with horns at the end. On the right of the monster, we see a decapitated female mannequin wearing a surgical rubber glove, a totem-like sculpture and a circular gold object. There are two vertical poles on the left of the monster, and at least two flying fish at the top left corner.

The background looks something between water and sky, and the presence of the fish has led some to suggest the setting is underwater.

The work as a whole looks and feels quite surrealistic, and it is indeed considered one of the earliest examples of surrealistic painting.

At the time Ernst painted The Elephant Celebes, surrealism had yet to be invented. However, proto-surrealistic movements had already been founded.

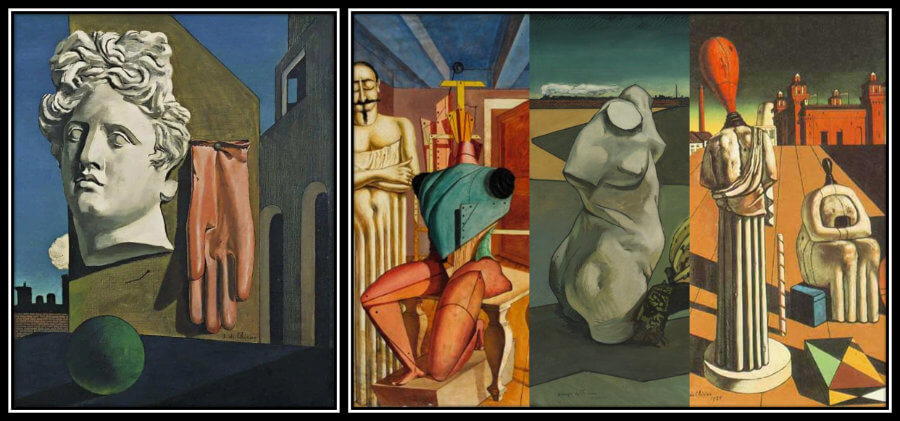

For example, Ernst was greatly inspired by the works of Italian painter Giorgio de Chirico, who invented metaphysical painting, a precursor of surrealism. That inspiration is seen in the way Ernst depicted various unrelated objects occupying the same space, as well as the way Ernst employed neutral colours with hardly any bright areas.

De Chirico’s influence is also directly seen in certain elements used, such as the bust and the surgical/rubber glove, common thematic elements in de Chirico’s paintings.

Ernst himself was pioneer in the art movement Dadaism, which had a tremendous influence in later surrealists. In short, Dadaism used humour and absurdity to mock social and conventional artistic values.

One of Dadaists’ favourite methods was that of collage – the usage of different materials such as paper, photographs or cloth arranged onto a single surface. Collage proved to be a useful tool for Dadaism because of its potential to create random works.

Despite using a single medium (oil on canvas), Ernst attempted to simulate different materials so as to give it a collage effect in The Elephant Celebes.

Cubism was also another movement that predated surrealism and greatly influenced it. Cubist motifs are present in the Elephant Celebes as seen, for example, in the “head” of the monster.

Ernst’s stature as one of the founders of surrealism is unquestionable. He surely had the talent and creativity that places him among the greatest surrealists of the 20th century.

Unfortunately, I’m not very excited about this particular work.

As you will notice from my analysis below, The Elephant Celebes is a tad too much “random” for my taste. Ernst rarely elaborated on the meaning of his paintings, and the viewer is left piecing together an impossible narrative.

In my opinion, when presenting an extreme bizarre artwork it is often beneficial to include at least an element that links different aspects of the composition.

This usually gives the viewer a sense of completion and self-containment. Even if the viewer cannot consciously pinpoint what that central element is, I wholeheartedly believe that this is a process that can also operate at an unconscious level.

With The Elephant Celebes I feel that central link is lacking, and the result is an absurd and unfathomable composition.

Here at Mindlybiz, The Elephant Celebes gets a rating of 2.5.

Weird! Definetely weird!

The possibility that Ernst let his mind wander and paint whatever cropped up in his mind via free-association and dream imagery can really only lead to one result: bizarre!

The combination of elements don’t make any sense and there isn’t a common thread connecting the disparate elements of the painting. It is difficult for me to imagine a weirder artwork.

The Elephant Celebes gets a bizarrometer score of 5.

When analysing an extremely bizarre work of art one of the things I do first is to get a gist of the message of the painting by looking at connecting features among the different elements. The Elephant Celebes has none.

As already mentioned in the Review section, Ernst was one of the founders of an art movement called Dadaism. Dadaism encouraged things like spontaneity, chance and randomness when producing an artwork, such that the end-result would defy formal and traditional artistic values.

It is likely that Ernst stayed true to this principle with The Elephant Celebes.

First, even though the work consists of a single medium (oil on paint), the collage effect often employed by Dadaists is clearly visible. This is a first indication that the work in question is mostly the result of chance encounters.

Second, having been influenced by the works of Freud, it is a possibility that Ernst let his mind wander freely, as the psychoanalytical technique of free-association dictates. Not only that, but dreams were a recurrent source of artistic creativity during the 1920s, so it is not unlikely that Ernst attempted to free-associate using his own dreams.

If we combine these two random aspects of artistic creation, we get a result which is just that: a random narrative. I believe there is no link that chains the disparate elements of the painting.

There could be allusions to the war (e.g., flying fish, smoke) and to the psychoanalytical theories of Freud (e.g., totem-like sculpture, round hole on the mechanical monster), but it isn’t clear if Ernst intended for these ideas to be related at all. Probably not.

This is even truer if we consider dreams as reflecting random activity in the brain. What do I mean by that?

Keep on reading to find out.

During the early years of psychoanalysis, psychoanalysts were in search of a therapy that could potentially treat many of the known psychological ailments at the time.

One of these therapies was hypnosis. Put simply, hypnosis consisted of ensuring the patient remained silent and focused, while the psychoanalyst whispered words and used gentle movements to soothe any symptoms that caused pain in the patient.

Now, hypnosis had many setbacks.

First, it wasn’t really generalisable. In fact, its effectiveness was very much restricted to the treatment of neurosis, which was what Freud devoted most of his time with.

Second, not everyone was equally suggestible, so hypnosis would not work for everyone.

Third, even if the patient could be hypnotised, the suggestions simply did not stick. For example, the therapist might have been able to calm down a patient suffering from anxiety using hypnosis in his office, but an emotional trigger could revert the patient back to the pre-hypnosis anxious state.

Freud was aware of the limitations of hypnosis, and was determined to find a more suitable alternative.

His idea was to find a technique with which he could access patients’ mental conflicts in a more direct and stable way.

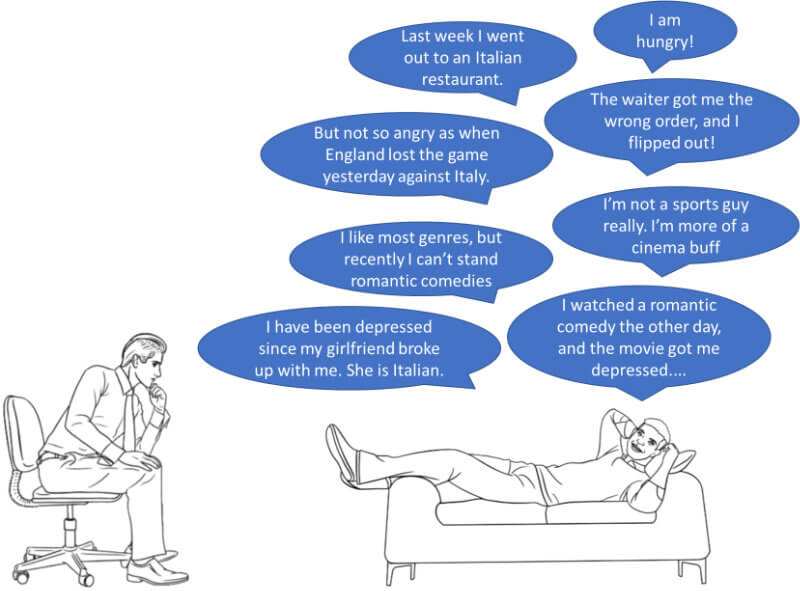

By mostly trial-and-error, Freud came up with the free-association technique.

The free-association technique consisted of asking the patient to narrate the initial experiences that the patient could immediately associate with the appearance of the symptoms.

Next, the therapist would ask the patient to say whatever spontaneous thoughts came into his/her head.

Importantly, the patients were told they shouldn’t think about or rationalise the thoughts. They should simply say out loud whatever images or words appeared in their minds.

Little by little, a trained psychoanalyst would be able to piece together these seemingly random thoughts into a (more or less) coherent past history of the patient.

Freud considered that every mental process must obey reason. So, if the patient tried to avoid a particular association (e.g., she corrected herself), it probably meant that this was the result of consciousness trying to prevent disturbing unconscious thoughts from emerging.

As soon as the psychoanalyst became aware of that resistance, he/she would intervene and investigate the reason for avoiding that particular association – for example, by asking further questions regarding that association.

It was the therapist’s task to successfully knock down the barriers of resistance, in order to bring the obscure content to consciousness. Only once this content was consciously exposed, could the patient manage the true wishes, emotions and desires related to the traumatic content.

It should be stressed that Freud subjected himself to the free-association technique he invented. In fact, he was his very first patient, and always reserved an hour or two per day for this activity, until his death.

So, in summary, free-association technique is nothing more than allowing the patient to quickly voice any thoughts, words or images that appear in his mind without deliberation, no matter how incoherent they may appear.

Even though free-association was invented as a means to treat disease, it can be applied more generally as a way to peak into the unconscious mind.

Free-association can also be used on dreams. Instead of directly asking patients what they think their dreams meant, they are encouraged to tell the analyst whatever comes to mind in relation to their dreams, regardless of how embarrassing and unpleasant these thoughts may appear.

To Freud, the free-association technique on dreams was indispensable for unravelling the true meaning of the dream.

But what if dreams have no meaning? What if the contents of your dream are nothing more than the by-product of erratic brain activity occurring during sleep?

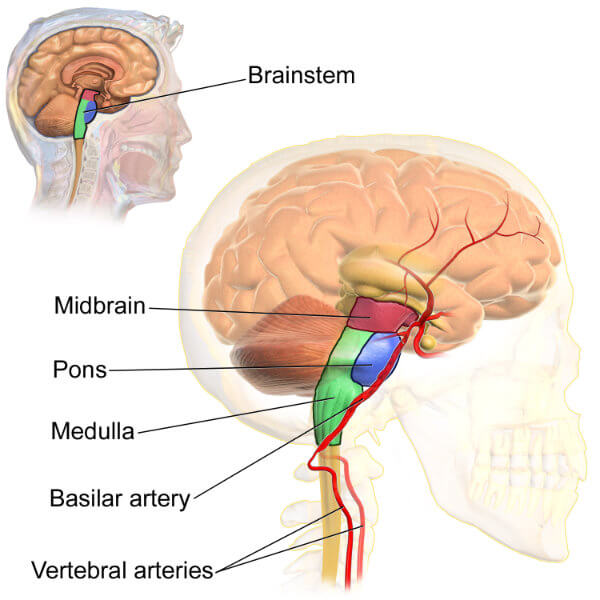

In the 70s, late American psychiatrists and dream researchers Dr. John Allan-Hobson and Dr. Robert McCarley of Harvard University put forward a neurobiological theory of dreams called “activation-synthesis hypothesis”.

According to this hypothesis, the genesis of a dream takes place in a location called the pontine reticular formation (PRF) situated in a part of the brain stem called the Pons (see figure above).

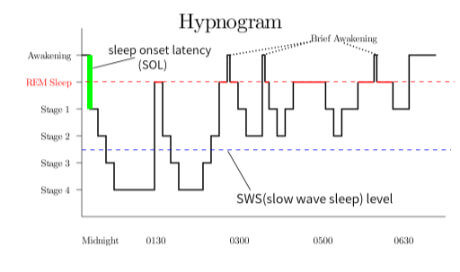

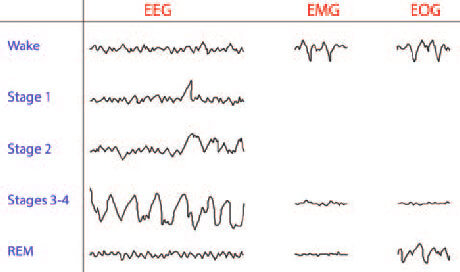

Research has shown that the firing of PRF neurons generates very distinct rapid-eye-movements (REM) while we are sleeping. It just happens that it is in this REM sleep stage when most (but not all) of our dreams take place (see Sleep Stages).

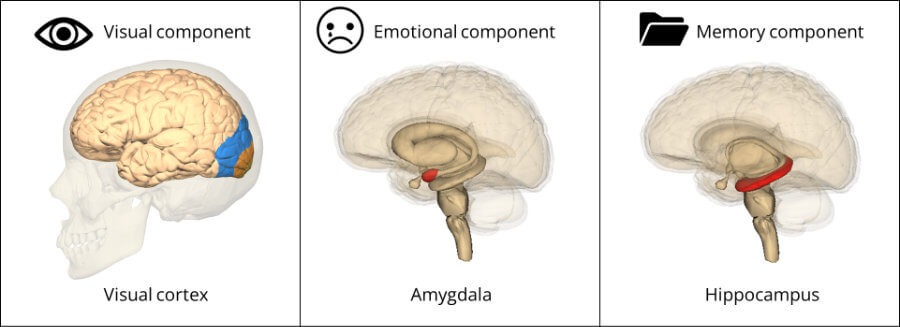

The activation of the PRF propagates to several brain areas of the cerebral cortex.

For example, it stimulates the visual regions (e.g., occipital cortex), explaining why our dreams are so visual.

It also stimulates the limbic system, a set of brain structures that are involved in emotion and memory processing (e.g., amygdala, hippocampus). The involvement of the limbic system during dreaming explains why our dreams can be so emotional-laden and why they often include known events, people and past experiences.

The brain is wired to process information. While we are awake, the brain interprets the information from our senses. For example, if we pick up our baby everything connected to that experienced (the touch, the smell, the baby’s laugh, the baby’s physical appearance, how we are feeling, etc.) is processed (or synthesised) by our brain to form an impression of that moment.

When we are dreaming, however, all the information the brain receives is generated internally (via this spontaneous and largely random firing from the PRF neurons).

Nevertheless, the brain is hard-coded to process that information. In the absence of external stimuli, the brain tries to synthethise the best it can these random signals from every part of the brain into a coherent narrative. Using the words of Hobson and McCarley:

“the forebrain may be making the best of a bad job in producing even partially coherent dream imagery from the relatively noisy signals sent up to it from the brain stem“

So, to recap, the activation part of the “activation-synthesis hypothesis” is really just the (mostly random) neuronal activation within the brain stem. The interpretation of these random signals from the brain stem by the cerebral cortex is the synthesis part of the “activation-synthesis hypothesis”.

As with most surrealists in the early and mid 20th century, Ernst had a penchant for psychoanalysis. Thus, it isn’t a stretch to believe that he made use of techniques that had been developed by Freud and his followers.

The free-association technique seems like a good candidate. You can do it on yourself, it is relatively easy to employ, you can get quick results, and, more importantly for the present article, you can use it as a means to interpret dreams.

Remember, The Elephant Celebes is considered one of the earliest examples of surrealistic painting. His predecessor, Giorgio de Chirico, began painting empty and dreamlike city squares with strange combinations of objects. De Chirico is often quoted as one of Ernst’s greatest influences, and we can easily see that influence in The Elephant Celebes.

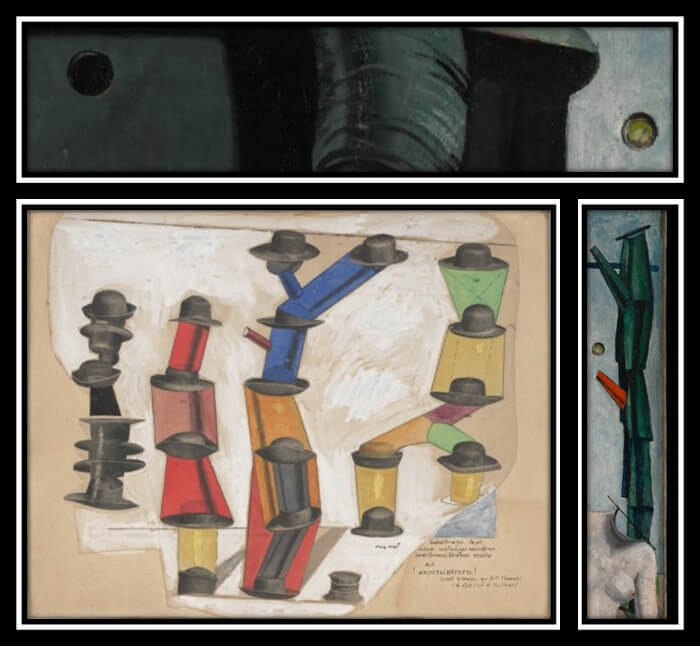

For starters, the bust of the decapitated female mannequin is reminiscent of de Chirico’s faceless or headless mannequins (see right figure above). Likewise, the surgical glove is a recurring element in surrealistic art, and is also depicted in de Chirico’s paintings (e.g., The Song of Love; see left figure above), where it has been interpreted as symbolising human absence.

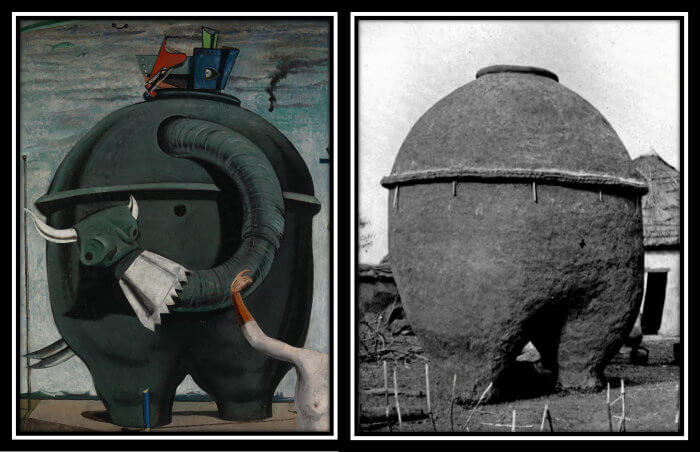

For the primary central element of the painting, the mechanical monster, Ernst drew inspiration from a photograph of a clay corn bin (a barrel used for storing corn) from the southern Sudanese Konkombwa people that he had come across in an anthropological journal (see figure above).

Art experts often mention at least two possibilities for the identity of the monster: an elephant, given the trunk-like appendage, or a bull, given the horns at the end of the trunk.

You might think that since the composition is called The Elephant Celebes, it is reasonable to assume it is an elephant.

However, the title comes from an old German satirical verse:

| German text (original) | English text (translation) |

|---|---|

| Der Elefant von Celebes hat hinten was Gelebes | The elephant from Celebes has something yellow on his buttocks |

| Der Elefant von Borneo, der hat dasselbe vorneo. | The elephant from Borneo has the same thing in front. |

| Der Elephant von Sumatra, der vögelt seine Großmama. | The elephant from Sumatra always shags his grandma |

| Der Elefant von Indien, der kann nicht das Loch findien. | The elephant from India can never find the hole. |

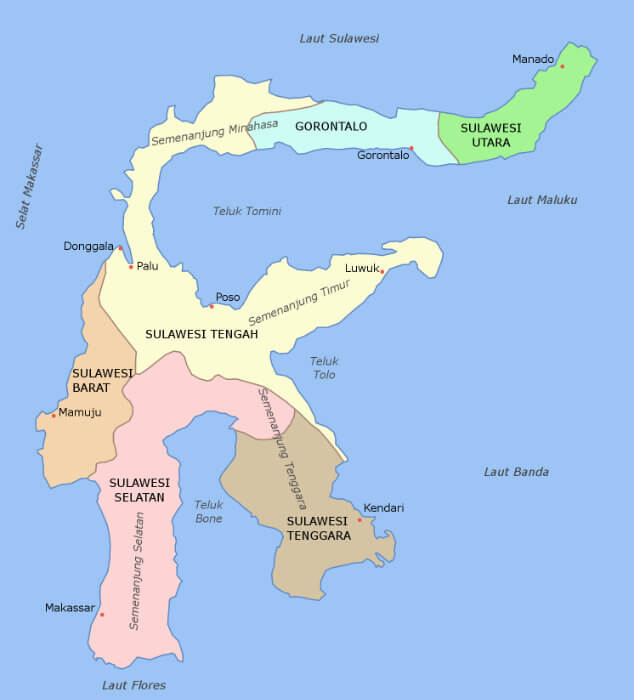

There is also an Indonesian island called Sulawesi which is also known as Celebes and has the shape of an elephant when viewed from above (see figure above).

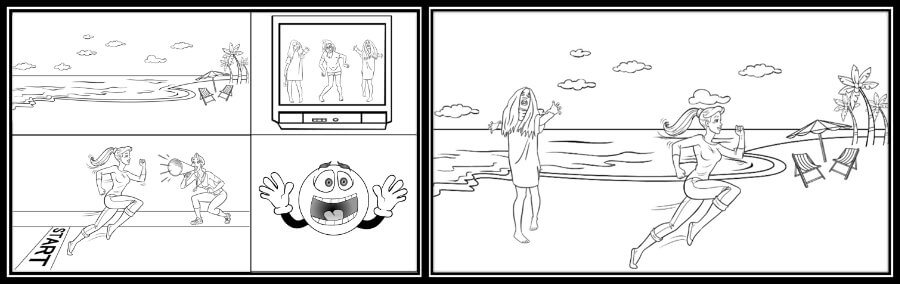

From then on, Ernst may have relied on free-association from his own dream(s), as the painting is notoriously hard to decipher. For instance, he could have dreamed about planes that looked like fish, crashed in the desert where a totem-like sculpture had been erected.

Psychoanalysts employ the free-association technique to explore associations that reveal the inner workings of their patients’ (unconscious) minds. In reality, however, what Ernst put on the canvas is most likely only fragments of the contents of his dreams.

Therefore, a complete psycho-dynamic interpretation of his work would probably turn out to be a fool’s errand, even for the most skilled analyst.

I spent a great deal of time explaining the activation-synthesis hypothesis, which essentially proposes that dreams images are simply the brain trying to make sense of erratic (and mostly random) activity emanating from the brain stem during REM sleep (see section Dreaming as random thoughts).

You may find it weird that, out of all dream theories, I chose one which completely disregards dream content. After all, most dream analysts are fervent believers that dreams cannot be random, they must contain messages from the unconscious, they must have meaning.

Allan Hobson, one of the proponents of activation-synthesis hypothesis, was very critical of Freud and his theory of dreams, coining phrases such as “Freud was 50% right and 100% wrong”.

Now, how is this relevant in interpreting the Elephant Celebes?

If the activation-synthesis hypothesis is correct (and there is evidence to suggest it is), then the idea that there is an unconscious message in our dreams is utter nonsense.

There is no hidden message.

Fragments of the dream can indicate some current emotional states because brain activity resulting from the random firing of the neuronal populations in the brain stem propagates to the emotional and memory centers of the brain.

However, the often illogical stories we dream are simply our brains’ attempt to piece together activity that happened to come from this or that area of the brain.

Consequently, according to the activation-synthesis hypothesis, doing free-association on dreams will logically lead to a random story, which by definition is uninterpretable.

Since Ernst probably used free-association in combination with dream imagery, the end result may have been something so outlandish and random that there is no point in trying to link the different elements of the Elephant Celebes into a logical narrative.

Not the analysis you were looking for, I know.

However, I’d like to point out that it is a real possibility that dreams may not mean anything at all, as the activation-synthesis hypothesis seems to suggest.

In my view, psychoanalysis will still need to convincingly be able to rebut this hypothesis. If it turns out it cannot, then making sense of a painting (or any other work for that matter) solely based on the artist’s dreams would be a rather futile task.

I would not want to end this article leaving you disappointed and without a “proper” interpretation of Ernst’s most famous work. I have to admit though that I’m not particularly convinced by any of the following interpretations, but here it goes anyway.

If we assume that the end of the trunk of the mechanical monster is indeed a bull, then the mannequin could represent princess Europa.

According to Greek mythology, Zeus, infatuated by Europa, decides to transform itself into a white bull. One day, Europa sees the bull and mounts on it. Zeus runs away with her on top, and later reveals his true identity to Europa, who then became the first queen of Crete.

In classical art, Europa is often depicted naked (or semi-naked) with one raised arm, just as the mannequin in Ernst’s work.

The flying fish could be easily mistaken by planes. The smoke could indicate the smoke emanated from a downed plane.

The Elephant Celebes was painted not long after the end of World War I, a war that Ernst fought as a soldier for four years. This experience was very traumatic to him, so some art analysts have suggested that these two elements may represent an allusion to war.

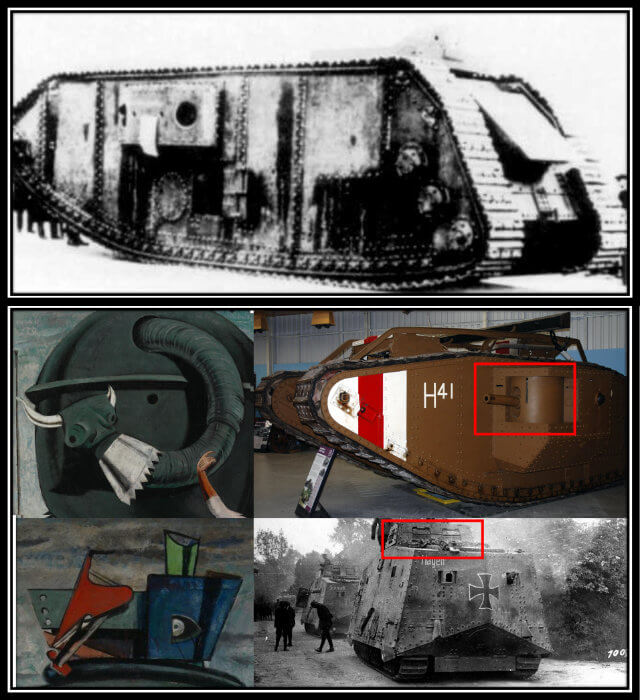

Moreover, one could probably see the similarities of the mechanical elephant with a military tank. For example, the round circular opening could indicate the same opening seen in some WWI tanks (see above), the trunk of the elephant could represent the tank gun, and the head of the elephant the periscope (what is used to observe the surroundings; see figure above).

Also, note how the decapitated mannequin seems to be inviting the mechanical monster. Maybe the decapitation is another allusion to the war – sadly, a sighting Ernst probably witnessed often in the battlefield.

All in all, those two aspects (Zeus’ abduction of Europa and the WWI symbolisation) could indicate Ernst’s wish to represent death and destruction with this painting.

There is also no shortage of psychoanalytical analysis of certain elements in the painting.

For example, some suggest that the totem-like sculpture is a phallic symbol (erected penises perhaps?). This sculpture resembles the towers from another of Ernst’s paintings, The Hat Makes the Man, where Ernst clipped and pasted illustrations from advertisements on the painted towers (see figure above).

Because The Hat Makes the Man had clearly been inspired by Freud’s work (who thought the hat was a symbol of male genitalia), it is reasonable to conclude that the same inspiration was at work in The Elephant Celebes.

Finally, there is also a sort of a coin next to the red branch of the tree sculpture. I have read a suggestion that maybe the coin is supposed to be pushed into the hole of the mechanical elephant’s circular opening with the vertical pole – perhaps symbolic copulation?

The Elephant Celebes appears to reflect both active thinking and random imagery. For instance, Ernst appears to have used actual photos for the mechanical monster, and there are a few obvious connections with other surrealistic works (such as de Chichiro’s The Song of Love). However, the combination of elements are so nonsensical that they defy interpretation, so most of the painting remains undecipherable.

Some of you will feel my analysis unsatisfying. Some will try to assign meaning to each and every element of the composition (I mention some of these meanings in the section Some interpretations).

But, let’s be honest. Every single one of us could come up with a justification for why Ernst painted this element like one or the other way. Maybe the flying fish represent planes? Maybe Ernst really liked to eat fish? Maybe he was fishing, and that gave him the idea to paint the fish? Maybe the fish symbolise phalluses? Maybe the two fish represent Ernst and his father? I could go on…

My point is, without a linking theme that connects the different elements, trying to interpret those elements is pointless, as they can have a multitude of interpretations.

Alas, Ernst gave no clues whatsoever what those elements may represent, which led me to conclude that he simply couldn’t, since the work is mostly the result of random thoughts and images.

One aspect seems consensual though. Like most of his contemporary surrealists, Ernst appears to have explored with dream imagery, probably even his own. Indeed, doing free-association using dreams would seem like a seductive approach in the early 20th century, when Freud theories were in vogue (and controversial).

Playing the devil’s advocate, if dreams are nothing but our brain’s attempt to interpret random signals from the brain stem, as some empirical evidence suggests, then doing free-association on this information can only result in a meaningless, jumbled-up narrative.

To me, The Elephant Celebes is really just that: a jumbled-up narrative.

It should be noted that psychoanalysts tend to reject theories of dreaming that discard any sort of meaning to the contents of dreams.

Since Ernst was a devout fan of psychoanalysis, you may find peculiar I decided to base the analysis of The Elephant Celebes on a purely neurobiological dream theory, especially since I have discussed psychoanalytical theories of dreaming in previous articles (see here and here).

However, I once had the privilege to attend a talk by Hobson (one of the founders of the activation-synthesis hypothesis I explained above), in which quite a few passionate psychoanalysts were present and who were fierce critics of Hobson’s theory. They were adamant that dreams had to have meaning and that that meaning was indeed close to Freud’s original ideas.

I have to say they did not come out on top.

You see, Hobson was in possession of actual scientific evidence, whereas the psychoanalysts could only report their beliefs, opinions and subjective experiences with their patients.

In fact, Hobson really only had to say: “OK, show me the evidence!” (he did literally say that when the psychoanalysts confronted him with questions at the end of his talk).

That said, the activation-synthesis hypothesis is by no means exempt from criticism, even in the form of scientific evidence. But the hypothesis is surely evolving as new data comes into light (see, for example, AIM).

The question is: will psychoanalysis be able to keep up?

See you in the next article!

This painting from Max Ernst is a masterpiece. Yes, Max used borrowed elements from other paintings but that should not confuse anyone as to what the painting is about. The painting was about how Europe after having experienced the first industrialized war in humanities history should have been doing everything in their power to never revisit such destruction and horror. This he had witnessed first hand as a soldier in WW1 for 4 years. Instead just 3 years after such a horror – Europe began lumbering towards an even more mechanized industrial conflict. Hitler and the other Fascists had after all moved from political rants and grumblings in beer halls in 1921 to a shooting revolution just 2 short years later (Beer Hall Putsch). Therefore Ernst paints the sky as apocalyptic in prediction of the future which he felt in his bones or perhaps subconscious was coming. The confusion of Europe and particularly Wiemar Germany and the decapitated Austrian Hungarian Empire where women were then permitted to have some rights is represented as a nude beheaded manikin leading the lumbering industrial war machine (Celebes).

I found this site looking for an image of the back of the Elephant Celebes for a sketch I am working on for a different composition. Therefore to understand why this painting is as important as Starry Night must be understood from the perspective of WW1 and the defeated Axis nations. Hyper inflation was raging in the ragged economies Axis economies. In 1921 the German currency became so inflated a US dollar was equal to 4,210,500,000,000 marks in 1921. Yes that was trillions of Marks to a single US dollar. Therefore surreal yes but within a very surreal existence for Max and most others at that time.

Hi Leo,

Thank you for your comment and analysis of the painting!

I briefly linked some of the elements of the painting to WWI but, honestly, felt that the more parsimonious explanation of being the product of free-association more likely.

For example, the idea for the mechanical monster appears to have been taken from an anthropological magazine, and it seems unlikely that Ernst based the idea of the elephant from his war experiences (a horse would have been more fitting, for example). More likely, Ernst found the idea of an elephant amusing, either in connection to the German satirical verse, to the elephant-shaped Indonesian island called Celebes, or simply to the shape of the clay corn bin.

Also, Ernst’s interest in Freudian theories, particularly the free-association technique, and their increasing relevance to the surrealists of the time might also indicate Ernst’s work mode. The decapitated nude female and the surgical glove are most likely influences from de Chirico, given the recurrence of these elements in the latter’s works (Ernst was also a great admirer of de Chirico’s paintings).

So, given these points, and a lack of analysis of the work by Ernst himself, I saw The Elephant of Celebes more as an experimental creation in the very early surrealistic movement rather than a homogenous symbolic artwork.

Of course, it’s just my interpretation. As you said, there is the possibility that Ernst’s “random” ideas may have been used within the scaffold of a larger and more meaningful idea, which Ernst remained silent about. It was that scaffold linking these seemingly random elements that I tried to identify in my analysis, but, in the end, I wasn’t convinced I’d found it…

Outstanding

Elephant Celebes

Okay, let’s break down “The Elephant Celebes,” which Ernst cooked up in 1921. Imagine stepping into a dream where nothing makes total sense, but it’s intriguing as heck. In the center, there’s this funky-looking elephant creature, all twisted up and wearing strange stuff. Around it are these mysterious shapes and structures, like something out of a surreal fairy tale.

Many thanks for your review!

Indeed, I agree that the entire painting looks as though we are viewing someone’s macabre dream, full of weird surrealistic elements.

You rated it 4.5 stars, is there any particular aspect of the painting that you consider exceptional?