This post is comprised of different sections

Take a look at our review of Guernica!

Learn more about the Spanish Civil War and "The Consequences of War" by Peter Paul Rubens! Or check out the full explanation Guernica Explained!

This post is comprised of different sections

Take a look at our review of Guernica!

Learn more about the Spanish Civil War and "The Consequences of War" by Peter Paul Rubens! Or check out the full explanation Guernica Explained!

Artist: Pablo Picasso

Year: 1935

Medium: Oil on canvas

Location: Museo Reina Sofía, Madrid, Spain

Dimensions: 349.3 cm x 776.6 cm

Our rating

Your rating

Pablo Picasso needs no introduction. The prolific Spanish painter produced over 50.000 works, including paintings, drawings and sculptures. Not only that, he co-founded an avant-garde movement that was to have a monumental impact in the art world, and which we have all heard at some point: Cubism.

Cubism was an artistic movement pioneered by Picasso and his friend Georges Braque in the early 20th century. It consists of decomposing three-dimensional subjects into a two-dimensional form, achieved by 1) reducing the subject to its bare-bone geometric shapes, 2) using multiple perspectives to show simultaneous points of view and 3) restrict the amount of shading in order to mingle foreground and background together.

Alas, no matter how much I force myself into appreciating cubist artworks, I fail to understand the hype in seeing distorted, childish figures. To me, they have always felt amateurish and aesthetically unpleasant.

You are probably thinking that I’m missing the point, since Cubism arose as a response to realistic painting that, granted, was becoming old school. So, cubists decided to break up the subject and reassemble it in a way that would give the viewer a more real experience and better understanding of the subject.

But take a look at Picasso’s painting “The Weeping Woman” above. Does that show you how a weeping woman really is, and what it should really look like (what Cubists purport to show with their art)?

Of course, Picasso’s intention all along was to shock people, by showing them a reality in a completely new level of abstraction, and got famous for it.

Art is subjective after all. An artwork doesn’t have to be beautiful, done with effort or have any meaning at all. Still, I end up questioning myself about the very meaning of art, if a new field that goes beyond traditional values automatically becomes something to value. Have you heard of “poop art”?

Anyway, let’s start reviewing and analysing Guernica, arguably the most famous Cubist artwork of all time.

In early 1937, the Spanish Republican government commissioned Picasso to produce a mural for the Spanish pavilion at the upcoming 1937 Paris World’s Fair.

After weeks having an “art block”, Picasso heard about the bombing of Guernica that had happened on the 26th of April of 1937 (a few weeks before the Paris World’s Fair), and immediately found his subject.

Within a bit over three weeks he had completed the job. That’s pretty impressive considering that the mural measures almost 3 meters high and 8 meters long and consists of a single canvas (as opposed to several smaller sewn canvas).

Guernica is now the most famous anti-war painting in the world, and with good reason. The emotional context assocatiated with this anti-war message is without a doubt very potent. The despair of the portrayed figures is quite expressive and the mood is unquestionably poignant. The immensely large dimensions of the painting together with the chaotic organisation of its elements was meant to dazzle viewers. And dazzled they are.

But I’ll be blunt – Guernica looks like a sloppy work to me. Picasso apparently completed Guernica in a little over three weeks, and one notices that it was a rush job (e.g., there are noticeable splashes, for example, between the teeth and jaw of the horse).

The monochromatic colour scheme employed by Picasso (technically, Picasso also used light pigments of blue and red, but most of the painting consists of grey and black) makes Guernica look quite dull to me.

I should point out that I have nothing against monochromatic paintings, quite the contrary! But seeing other (almost always colourful) cubist paintings from Picasso, it feels odd that he would miss the opportunity to go wild with Guernica.

Perhaps it was Picasso’s intention. Some suggest the use of black and grey was meant to convey pain, chaos and suffering. But, surely, wouldn’t even moderate tones of red have made the painting much more dramatic and interesting? Maybe Picasso did not wish to manipulate the viewers emotions by adding colours, as it has been proposed, but that seems a bit of a post hoc explanation.

Moreover, Guernica was allegedly based on “The Consequences of War” by Rubens (and possibly others, although they won’t be covered here), a work Picasso never fully acknowledged (read more on that below).

Of course, it might be a purely gigantic coincidence that the two paintings share numerous details. However, Picasso had an allegedly encyclopedic knowledge of art, and, to make the case stronger, Rubens was one of his favourite painters! Now, how on earth would he miss the obvious similarities with the Horrors of War? Again, it might all be just a coincidence, I guess we will never know.

Lastly, you may have already figured out that that I’m no big fan of Cubism. The problem is that I find the ideas of Cubism paradoxical. Cubists thought realism was not accurate enough as a way to show how things really are. So, bye-bye perspective and graded shading, and hello distortion and disfiguration?!?

And I know Picasso was a terrific painter, that’s not the point. I’ve been to both the Museu Picasso in Barcelona and the Museo Picasso in Malaga, and I was really impressed with some of the lesser-known works from Picasso. In fact, I was surprised that they are not given as much credit as Guernica.

On a positive note, I do like certain aspects of the painting. For example, Picasso requested a specific kind of paint that would have the least amount of gloss possible. The result it that the brighter parts of the painting are very luminous, whereas the blacks are matte black.

It is also interesting that there are actually no references to the actual bombing of Guernica: there are no identifiable landmarks, or images evoking bombing, no allusions to politics or to the Spanish Civil War. Only the title suggests a connection with the wrecked town.

It is as though Picasso wished the painting to symbolise the suffering caused by any war.

I have to say that I feel very uncomfortable giving a low score to a work of art that has been praised worldwide for decades, and which is considered to be a masterpiece by many art experts.

Nevertheless, I have to stay true to my beliefs, and Guernica simply doesn’t do it for me. As described above, the distorted and graceless figures, tedious palette of black and grey and the absence of a proper acknowledgment of works that most likely inspired Picasso, really takes my enthusiasm for this work.

Here at mindlybiz I’m giving Guernica a rating of 2.

Even though Guernica is often considered to be a cubist surrealistic painting, the theme of the composition as a whole is not hard to decipher: the devastation and suffering caused by war.

There are a few oddities here and there such as the lightbulb or the woman carrying a torch, which definitely require interpretation. However, even these elements can be easily framed within the general theme of war.

For these reasons, Guernica gets a Bizarrometer score of 2.5.

In order to make sense of Guernica, it’s critical to learn about the political and historical context in which Picasso was living, in particular the Spanish Civil War.

In January 1937 the Spanish Republic commissioned Picasso to produce a large mural to be exhibited in the Spanish Pavilion at the 1937 Paris World’s Fair.

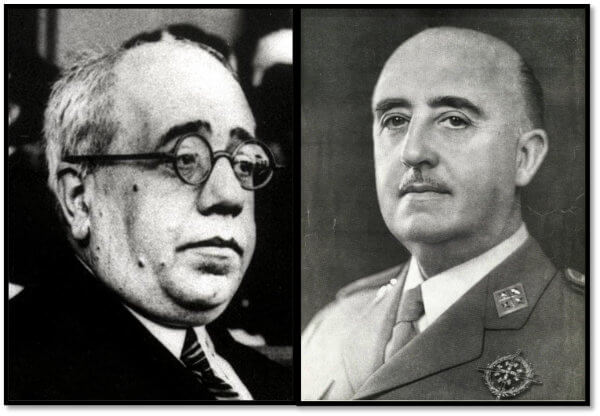

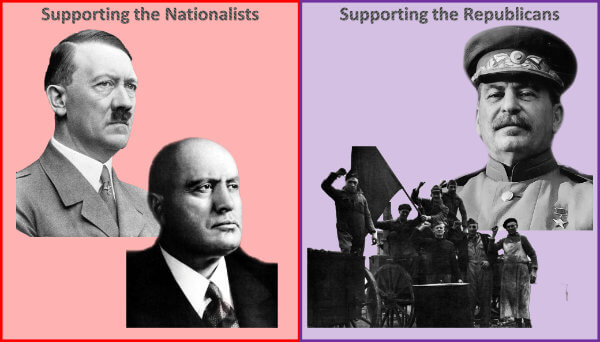

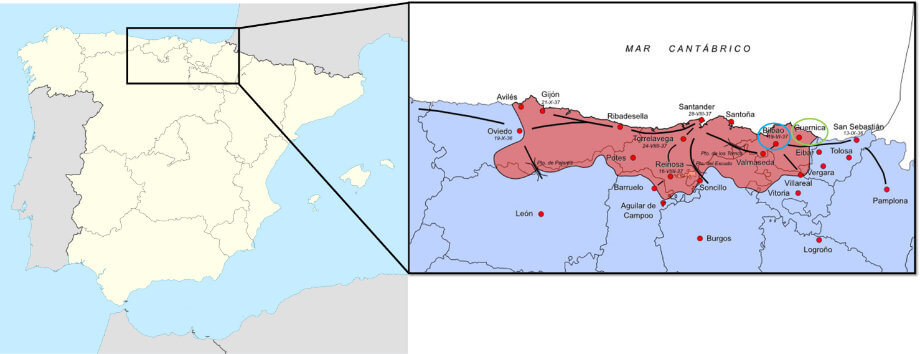

The Spanish Republic had been at war with the Nationalists led by Francisco Franco and his allies, Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. The Republicans, on the other hand, counted with the help of Russia and volunteers from all over the world.

By early 1937 most of industrial north of Spain was under Republican control. Franco decided to bomb the town of Guernica, which he believed would facilitate the take over of Bilbao and eventually the entire northern region.

Picasso, a fervent anti-fascist, applauded the efforts of the Republicans in fighting off the rebels, but he was somewhat reluctant to get involved into politics and worked disheartened on the mural during the initial months. The bombing of Guernica changed that.

The horrific photos of the bombing on the newspapers galvanised Picasso into action, and he completed the work in less than a month.

The painting as a whole is rather chaotic, the figures are almost juxtaposed on one another and we see destruction and suffering everywhere. This was of course intentional, as Picasso wished to shock the viewer with depictions of chaos and destruction caused by war.

This suffering is pretty evident in the figures’ facial expressions and body postures, particularly the horse, which has a priveleged position at the center of the canvas, and which evinces excruciating pain.

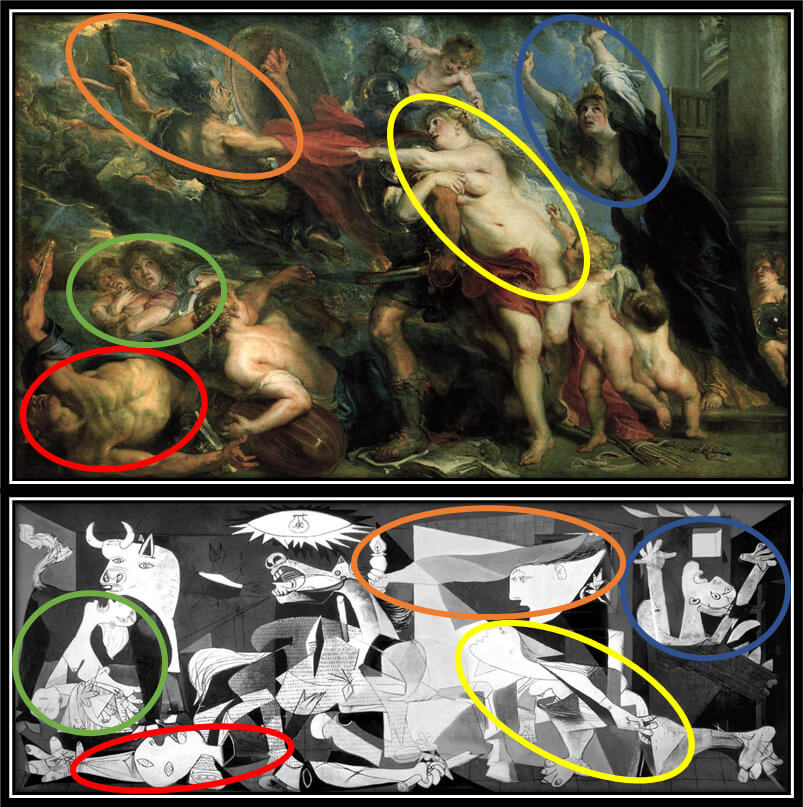

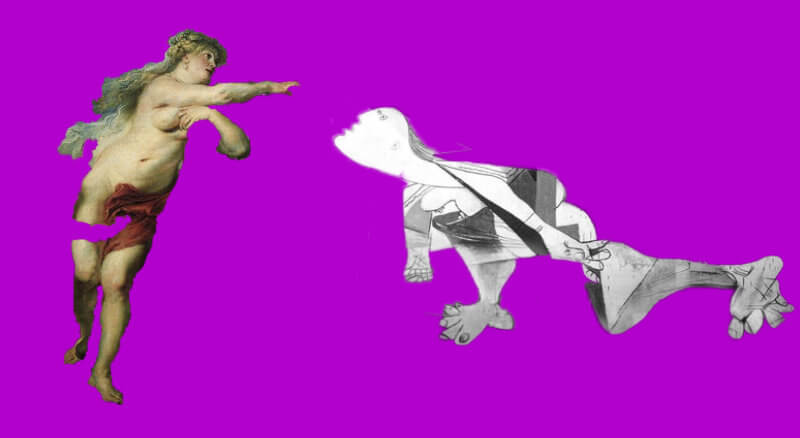

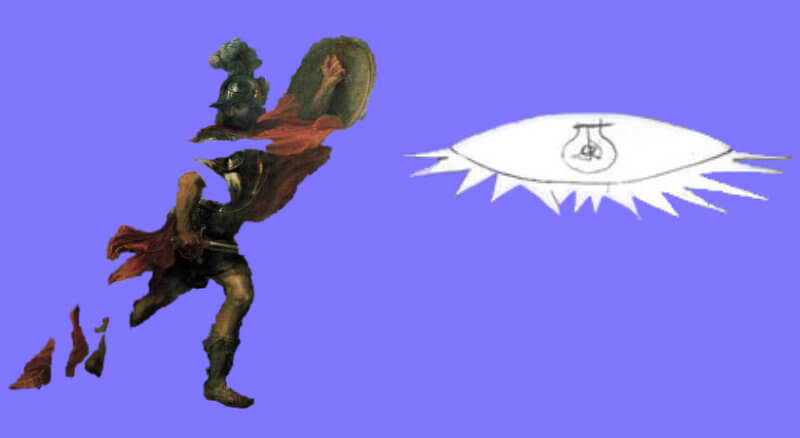

In her book “Picasso’s Guernica after Rubens’s Horrors of War”, Alice Doumanian Tankard proposed that Guernica may be based on a mirror-image of Rubens’ 1888 painting “The Consequences of War”.

This can be most easily seen if we flip Rubens’ painting horizontally as I did above.

Hopefully you can see what made Tankard advance her hypothesis. Many of the figures in Rubens’ work appear to have a homologous version in Picasso’s work: For example, a woman with her arms stretched up, a woman holding a dead child in her arms, an unconscious man on the ground, a woman leaning towards the center, a woman carrying a torch, all appear in both paintings.

Picasso admired Rubens so it’s not a stretch to imagine that Rubens’ painting could have influenced Picasso. In fact, just as “The Consequences of War” was painted as a response to the Thirty Years War, so was Guernica painted as a response to the Spanish Civil War.

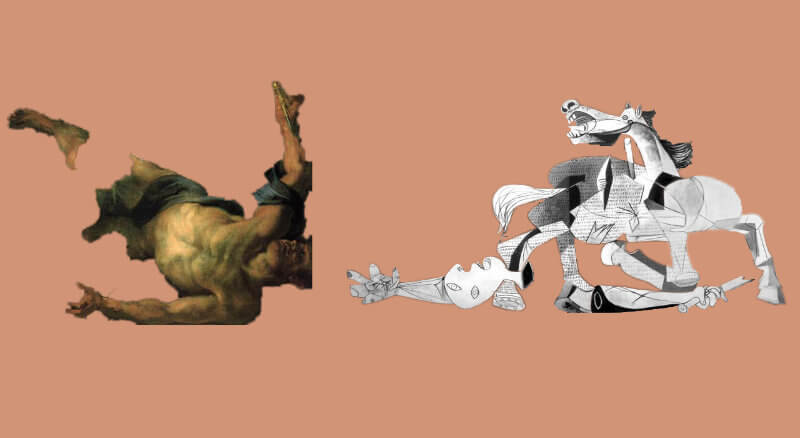

Obviously, differences between the Rubens’ and Picasso’s work exist. The most obvious one is the absence of Rubens’ Mars depicted at the center of his painting. Picasso chose to place the wounded horse at the center of the canvas, perhaps wishing to accentuate the agony that the Spanish civilians were experiencing in this war.

Before expounding on this analysis, as always, let me share with you some facts I learned while researching Guernica, which will be helpful in the interpretation of Picasso’s work.

After the World War I, Spain was a deeply polarised country. Opposition to the monarchy grew stronger after a series of debacles that saw King Alphonso losing the majority support of his army. The financial gap between the wealthy and the middle class also began to widen by the day, drawing both social classes to political extremist ideas.

In 1931 local elections were held that saw the opposition party, the Republicans – a conglomerate of political movements including communists, socialists, anarchists and syndicalists (all very anti-monarchy) – victorious. As a result the King was sent into exile, and a democratic republic was declared.

Although many reforms were initially planned, they were controversial and slow to put to practice, which alienated both the left and right. Several strikes erupted across Spain, eventually cracking down the government. At the General Elections of 1933, CEDA, a Catholic conservative political party with fascist ideologies, won the majority of the seats.

Unhappy with the prospect of a conservative regime in power far-left political factions rose up and took over the province Asturias by force. As a response, the army sent a loyal monarchist general called Francisco Franco, to quell the revolution, which he did with appalling brutality.

The left-wing parties realised that the only way to regain power and defeat the far-right would be to cooperate. And so they formed a coalition, the Popular Front, which stood against CEDA at the General Elections of 1936. The Popular Front won narrowly.

Fearing that the land would plunge into communism, a far-right military faction within the Spanish army launched a coup shortly after the elections.

Mutiny first erupted in Spain’s colony in Morocco. Franco joined them and formed the Nationalist movement – a movement which, he believed, would save Spain from the threat of communism.

But there Franco faced a problem: in order to get the fearsome army of Africa to mainland Spain, he would need to cross the strait of Gilbratar, which, at the time, was controlled by the Republicans-sided navy.

So Franco decided to ask for help from Adolph Hitler and Benito Mussolini. And both agreed.

Hitler’s decision to get involved in Spain’s war and side with the Nationalists was largely motivated by the prospect of having a state friendly to Nazi-Germany and, at the same time, inimical to France. Also, this involvement would provide a distraction from German rearmament, as well as a testing ground for Germany’s latest military technology and fighting tactics.

And so, Hitler sent Luftwaffe airplanes, tanks and thousands of troops to Spain. Mussolini, in turn, sent about 50.000 men and hundreds of aircraft.

Once Franco and his army of Africa arrived in continental Spain, the Nationalists immediately began pushing north towards Madrid. The advance was particularly fierce – a sort of Iberian blitzkrieg. With the help of their German and Italian allies, the ruthless and extremely disciplined army of Africa pushed through connecting the southern with the northern front.

The Republicans turned to Britain, France and the Soviet Union, which, fearing that their intervention would initiate an European war, declared a policy of non-intervention. Both Gemany and Italy also agreed to this policy, but blatantly ignored it.

The leader of the Soviet Union, Joseph Stalin, realising that Germany ignored the pact, decided to help the Republicans by providing tanks and fighter aircraft along with miliaray advisors. Not out of kindness, one must say. In fact, Stalin saw it rather advantagous to have a communist-friendly country in Europe. In addition, a Spanish war would keep Germany and Italy occupied, which would give Stalin precious time to build Soviet Union’s own military strength.

The Republicans also counted with the help of thousands of left-wing British, French, German and American volunteers (the so-called International Brigades).

However, the number of volunteers fighting for the Republicans was modest compared to the assistance Franco had received. As brave as the Republicans were, most volunteers were under-equipped and lacked proper military training. They were no match for the professional soldiers under the leadership of Franco (particularly the disciplined army of Africa), as well as the ultra-modern weaponry provided by Germany and Italy.

After seizing key cities in southern Spain, Franco and his Nationalist troops concentrated their efforts on the northern front.

Even though northern Spain was mostly under the control of the Nationalists, the Basque country, which included the city of Bilbao (a major industrial centre in Spain), was still under Republican control. The Nationalists believed that taking over the city would put a quick end to the war in northern Spain, and potentially decide the course of the war.

Guernica, a small village of 7000 inhabitants and only 30 kilometers from Bilbao, was what stood between the Nationalist advance and the capture of Bilbao. In addition, Guernica served as a retreat point for Republicans fleeing, and was the location of a weapons factory.

By this time, Germany had reorganised its existing military units in Spain, and formed a new legion called the Condor Legion, which consisted of modern bombers and fighters. In April 1937, under Franco’s orders, the Condor Legion as well as Italian bombers were deployed to Guernica.

The attack on Guernica was gruesome. Prior to the attack, bridges and roads had been completely destroyed to restrict the movement of Republican troops, and effectively lock everyone inside the town.

The Condor Legion employed a combined tactic involving both explosive and incendiary bombs, as well as indiscriminate machine gunning of unarmed civilians.

Over 3000 bombs were dropped on the town, which resulted in the destruction of about 75% of the buildings. Although estimates vary, it is believed that about 200-300 people were killed on that day, and many more were severely wounded. Most victims were children and women, since men were away fighting for the Republicans.

The defender’s morale dropped to its lowest, and any will to resist was crushed. Nationalists had no trouble taking complete control of the town.

A few months after the bombing of Guernica, Bilbao fell to the Nationalists, paving the way for Franco’s victory over the Republicans and complete domination of the country.

Peter Paul Rubens was a Flemish painter from the XVII century.

He lived during a period called the Thirty-years war. This conflict, which spanned 30 years (1618-1648), was one of the most destructive events in the history of Europe, and responsible for the deaths of millions of people, with some territories seeing a staggering decline in population.

Looting and setting fields on fire was in the order of the day; famine and disease were rampant.

Sometime between 1637-1638, Artist Justus Sustermans commissioned Rubens to produce “The Consequences of War” (sometimes also named “The Horrors of War”).

Rubens was deeply affected by how war had been ravaging his native land, and “The Consequences of War” serves a commentary showing the destruction in Europe caused by this devastating war.

“The Consequences of War” is an allegory. That is, the characters and events depicted in the painting are merely symbols representing moral, political or religious ideas.

Below, I’ll briefly describe some of the major elements in this painting and their putative meaning.

In Ancient Rome, the temple of Janus was a small temple located in Rome. During times of peace, the doors of the temple would remain closed, whereas during periods of war, the temple’s doors would be opened.

Janus is the god of beginnings and passages and is often portrayed as two heads facing away from each other (see figure above).

In Ruben’s painting, we can see the temple of Janus located at the far left, flanked by two enormous columns. A sculpture of Janus (with its distinctive two faces placed in opposite directions) can also be seen above the gates of the temple. The gates are open, indicating war.

The warrior at the centre of the composition is Mars, the Roman god of War. His red cape emphasises his identity as the god of War.

In the painting, Mars appears to have burst out of the temple of Janus, unleashing terror. He is carrying a shield and a bloodied sword, threatening the people around him.

In Roman mythology, Mars revels in fighting, and was believed to be the protector of Rome.

The female figure grasping Mars’ right arm is Venus, the Roman goddess of love and Mars’ mistress.

Venus is futilely attempting to restrain Mars’ attack with caresses and embraces. She counts with the help of Cupid and Amors in her endeavor to placate Mars and maintain peace.

Notice how Venus is much brighter than the rest of the painting. Most of the canvas has a darker tonality, therefore depicting discord, destruction, sadness.

Venus and her helpers, on the other hand, are much brighter, and represent the love, beauty and rays of hope that still linger among humans in spite of this devastating war.

In Greek mythology, furies are goddesses of vengeance. Alecto is one of the three furies and personifies anger.

According to myth, Alecto was recruited by Juno to set off the Trojan War. After King Turnus mocked her persuasion attempts at igniting the war against the Trojans, Alecto used a burning torch to bring King Turnus’ blood to “boil with passion for war”.

In Rubens’ painting, Alecto is galvanising Mars into action. She has a terrifying look in her eyes and is waving her torch above Mars, inciting him to wreak havoc.

The two monsters at the upper right corner of the canvas symbolise pestilence and famine, terrible consequences of war.

On the right side of the painting we can see a terrified woman carrying a (possibly dead) child in her arms.

According to Rubens, these two figures represent the bruise that war causes on fecundity, procreation and charity.

The woman lying on the floor with a lute and her back towards us personifies Harmony.

The neck of the lute is broken, symbolising that even music is not left unscathed by the destruction caused by war.

On the right corner a man has been thrown to the ground. He is an architect, as suggested by the instruments he is still holding in his hands such as a compass.

With it, Rubens wanted to convey the idea that war destroys everything of beauty that man is able to create at times of peace.

The woman on the left of the painting with her arms stretched up and a look of despair on her face symbolises Europe.

Although a crown is visible on her head, she has been robbed of all her jewels and ornaments. This means that Europe’s wealth (not just material wealth, but also stability) has been stripped away. She has dropped a globe (a defining attribute of Europe), which has been caught by one of the Amores.

This figure clearly represents the continent of Europe, which, at the time, was being ravaged by destruction and chaos caused by the Thirty Years war.

The arrows on the ground bundled together with a leather band are supposed to symbolise Concord (a symbol of unity and agreement in a society). The band that held the arrows together has been loosened however, suggesting discord among people.

Next to the arrows is a cauduceus, a symbol of peace.

Both of these objects appear to have been neglected and tossed aside. Rubens clearly wished to depict how qualities such as friendship, unity, agreement, have all been contaminated and now only disunity and discord reign.

Also, note how Mars is stepping on a book and a drawing on a paper, a clear suggestion of war’s pernicious effects on the arts and letters (and a society’s culture in general).

Likewise, Harmony’s broken lute and the unconscious Architect holding a compass could symbolise the destruction of music and architecture.

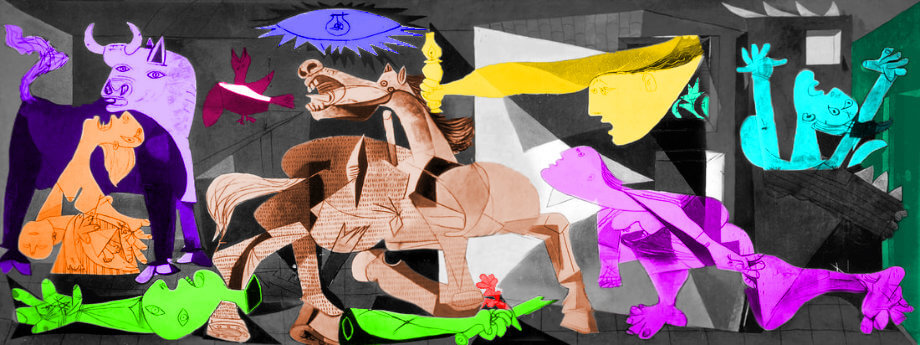

In this analysis, I decided to dissect Guernica into its main constituents and draw a parallel to Rubens’ characters in his “The Consequences of War”. Even though most of the ideas in this article are based on the book “Picasso’s Guernica after Rubens’s Horrors of War” by Alice Doumanian Tankard, some of my interpretations will differ from Tankard’s.

It’s interesting that Picasso initially placed most characters in the position the characters in Rubens’ work appear. For example, the woman with stretched arms, who appears to be the equivalent of Europe in Rubens’ painting, was initially drawn on the left side of the canvas.

Later Picasso decided to flip their positions in the canvas, the reasons for which are not entirely clear. Did Picasso intend to make the link between Guernica and “The Consequences of War” less conspicuous?

In the sections below, the titles will indicate a character in Rubens’ painting on the left side of the hyphen, and the homologous element in Picasso’s work on the right side of the hyphen (e.g., Mars – Light bulb).

The Venus in Rubens’ painting bears many similarities with the bent woman on the right of Picasso’s work (see images above).

Both are mostly nude, their hairs are pushed back, a veil is visible on their backs, and both are striding towards the centre of the painting.

In Rubens’ work, Venus is looking at, and leaning on, Mars. In Picasso’s painting, the woman is looking in the direction of the light bulb, which, as I’ll argue below, is a symbolic war figure just as Rubens’ Mars.

Another interesting parallel is that both women are showing grit and determination in ending the war. Just as Venus in Rubens’ work tries to put an end to Mars’ rampage, so is Picasso’s woman pursuing the destructive light bulb despite her injured leg, as if intent to put a stop to the devastation the bulb (war) is causing.

In Picasso’s painting, the female figure with stretched arms is likely the analogous of Rubens’ Europe. In both works, her heads are flung back, arms stretched up, eyes rolled up and mouth agape.

It’s just about visible tears forming in Rubens’ Europe. In Picasso’s work the woman with arms strechted up has eyes in the shape of tears.

Furthermore, in Picasso’s work, this woman has a kind of hat on her head, mimicking the crown worn by Rubens’ Europe.

Also, note the shape of the right hand of Picasso’s “Europe”. It appears to be an airplane, perhaps Picasso’s subtle clue that links this painting to the Nazi bombers that destroyed Guernica.

Finally, it is interesting that Picasso chose “Europe” to be one of the most shocking elements of the painting (a woman being burned alive). Picasso was probably foreseeing the terrible consequences fascism would have on much of Europe.

Rubens painted a Cupid above Venus, trying desperately to help her in her efforts to appease Mars. In Picasso’s painting, there is no Cupid, but Picasso drew a wounded dove between the horse and the bull.

In classical art, the dove symbolises the holy spirit as well as a symbol of peace. With this detail, Picasso meant that peace is all but destroyed by war, just as Cupid ultimately fails to halt Mars’ turmoil and maintain peace.

In Rubens’ painting the temple of Janus is just visible behind Europe. In Guernica, “Europe” is also standing behind what it looks like an open door.

Above the gate of the temple, Rubens painted a niche containing the two-faced bust of Janus. In Guernica, a small window is shown at the left of the door, although no bust is present.

In Guernica, we see a woman with her left side of her face turned towards the viewer, her mouth is agape, eyebrows are raised, eyes wide open, just like Rubens’ Alecto. Also, the hair streams of Picasso’s figure resemble the chaotic hairs of Rubens’ Alecto.

Interestingly, the woman in Picasso’s painting isn’t inciting violence, which stands in stark contrast to Rubens’ Alecto, who is egging on Mars. Instead, she comes through a window into the battle, and her facial expression is of shock and horror by what she is witnessing.

There have been suggestions that this woman may represent Russia, mostly because the signs just under her neck resemble a hammer and sickle, a well-known communist symbol. The kerosene lamp would, then, symbolise the help Russia provided the Republicans.

By transforming Alecto from a vengeful and instigator figure into a compassionate and full of hope character, Picasso perhaps hoped that the war would come to an end, and the Republicans would come out victorious.

In both Picasso’s and Rubens’ works, there is a woman carrying a child on her arms. Both mothers have their mouths wide opened, while their faces are turned upwards in horror. Furthermore, the child appears to be dead, or unconscious, in both Rubens’ and Picasso’s paintings.

This figure is perhaps the most dramatic of the entire painting, and at the same time, the most pertinent. The bombing of Guernica was a brutal attack on unarmed civilians, most of whom were women and children, as men were fighting away for the Republicans.

With this element, Picasso wished to depict the suffering of women and children from the horrors of the bombing.

In Rubens’ painting, the monsters of Pestilence and Famine appear behind the woman carrying a child. In Picasso’s painting, a bull is shown behind the woman with the child.

As with many of the other figures, the Bull is positioned in mirror image to Rubens’ Pestilence. Both monsters in Rubens’ painting have their mouths opened in a threatening pose, just as the Bull in Picasso’s painting.

Pestilence is often depicted as a hybrid creature: half human, half animal. It’s interesting to note that Picasso drew a hybrid creature with a human face and a body of a bull in early drawings of Guernica.

Picasso once mentioned that the Bull represents darkness, coldness and cruelty. Perhaps Picasso intended it to be a representation of Fascism, or of Francisco Franco himself.

Also, play close attention to its tail. It’s giving off smoke, perhaps a symbolism of the smoke emanated from the fires caused by the bombings.

Moreover, in some sketches Picasso made of Guernica, the Bull is depicted raping the female figure, indicating that the Bull is a representation of evil.

Picasso reserved the center of his painting to the horse. The horse is severely wounded (a deep cut is visible on its body). The mouth is opened wide and the tongue is sticking out, suggesting that it is experiencing extreme pain.

The fallen soldier with a severed arm is holding a broken sword on his right hand. There is an obvious parallel here with the Architect in Rubens’ painting. Both are lying on the ground, eyes are opened but empty, as if unconscious. Their left hands are empty, but their right hands are holding the instrument of their profession (the architect, a compass; the soldier, a sword).

Both the horse and its soldier likely represent the Republicans, and their courage to put a stop to the madness of war. Note how the horse is turning his head towards and shrieking at the impassive bull, as if it were the last sacrifice. Also, note how the sword has been broken in half, perhaps a representation of defencelessness.

It is also important to consider the relationship between the Bull, the soldier and the horse. Bullfighting was (and still is) a typical Spanish tradition. The soldier with a broken sword could represent a matador. But whereas bull fighting usually ends with a victorious matador, in Guernica it is the matador and his horse who are slaughtered.

Perhaps, with this twist, Picasso wished to shake viewers up, making them aware of the desecration Franco and his fascist allies were commiting in Spain.

In Ruben’s painting, between the Architect and Venus, we can see Harmony lying on the ground, holding a broken lute. Harmony is the goddess of, well, harmony and concord.

In Picasso’s work, we can see a poppy between the fallen soldier and the woman with an injured leg. Why a poppy, out of all things?

Well, white poppies are flowers that came to symbolise peace. In fact, this symbolism was beginning to emerge at pretty much about the time Picasso was working on Guernica.

So, Picasso’s poppy represents a ray of hope that not all is lost, and peace (concord) is still attainable.

There is no male figure in Picasso’s painting that can be directly related to that of Rubens’ Mars.

However, I would like to draw your attention to the light bulb at the top of the painting. This is one of the most intriguing elements in Guernica, which has received at least two contrasting interpretations.

First, because it has a shape of an eye, many art experts interpreted it as the eye of God looking down on the horrors of the war. The reason for this is that, classically, whenever light was present, it would usually represent the presence of God.

The second interpretation of the light bulb is that it represents the destructive technological weaponry used in the war. The word for bulb in Spanish is “Bombilla” which is similar in sound to the word “Bomba” (bomb in English).

Rather than thinking of the light bulb in terms of either the first or second interpretation as it’s often done, I believe that the two interpretations are not mutually exclusive. Perhaps a case could be made that the light bulb is the universal engine of war, prepared to run amok in the places it visits. In other words, Mars.

As noted by Tankard in her book, Picasso placed a directional arrow in more or less the same position where a set of arrows are located in Rubens painting. “Flecha” is the spanish word for arrow, and just as the English word, “flecha” can be used in both contexts: for shooting arrows (as in Rubens’ painting) and as directional arrows (as in Picasso’s painting).

The smoke that permeates the background of Rubens’ painting has been replaced by flames in Picasso’s painting.

Guernica’s anti-war message is very potent, and the painting has, deservedly, become an icon in anti-war movements across the world.

In this article, I focused on the similarities to Rubens’ “The Consequences of War”, showing how almost every figure in Picasso’s work has a potentially corresponding element in the allegorical work of Rubens.

Rubens’ Mars and Picasso’s lightbulb as the engine of War; Rubens’ Venus and Picasso’s injured woman courageously attempting to stop war; Rubens’ Europe and Picasso’s woman in the burning building as a symbolism of the devastation caused by war; Rubens’ fallen architect and Picasso’s fallen soldier, as brave martyrs of the war; Rubens’ Harmony and Picasso’s poppy as longing for peace; Rubens’ monsters and Picasso’s Bull as the scourge of war.

Indeed, just as Rubens’ “The Consequences of War” was produced as a response to the Thirty Years War that caused so much affliction in Europe, Guernica is the contemporaneous response of a tragic event that caused so much suffering and decided the course of the Spanish Civil War.

Unfortunately, apart from the message, not much more excites me about this painting. Aesthetically, I find Guernica lacklustre. Its impressive dimensions cannot conceal the fact that it was a rush job, and the lack of proper references to works that most likely influenced Picasso is regrettable (although, to be fair, there is no proof that Picasso really based his painting on “The Consequences of War”, or any other painting for that matter).

No doubt Picasso was a terrific painter who had mastered classical techniques from a very early age. I find some of his earlier works impressive, but Guernica… I feel the hype has more to do with Picasso’s exceptional ability to self-promote.

Notwithstanding the striking similarity between Rubens’ “The Consequences of War” and Picasso’s Guernica, it would be naive to conclude that Rubens’ work served as the only inspiration for Picasso’s painting.

In fact, Guernica was likely inspired by a many great deal of paintings, among which The Consequences of War would just be one of them. For example, Goya’s “El tres de Mayo”, Michelangelos Pieta, Rafael’s The Fire of the Borgo, Caravaggio’s Conversion of St. Paul, just to name a few, have all been proposed as precursors of Guernica.

A compendious analysis of all these works and their relationship to Guernica would probably require several volumes, so my efforts centered on Rubens’ work, which I believe reverberates more strongly in Guernica.

See you in the next article!

Books

Tankard, Alice Doumanian. Picasso’s Guernica after Rubens’s Horrors of War.

Documentaries

World War II in HD Colour – episode “The Gathering Storm”

Youtube

About Picasso’s Guernica

About Rubens’ “The Consequences of War”

About the Spanish Civil War

Only with a simply contrast b/w lenguage, that a child can easily undrestand, if you are a human(not you in this case).

With primeval figures in their desperation and most dramatic moments in their life and dead.

Almost like graffiti artists do in the same size today.

He brings us “The Horror of War”, but he is also warning to us.

A different war is coming.

The Spanish Civil War was reported by important journalists of the time.

This picture alerted and made the world aware of the pain and suffering that this new type of war brought with it, the so-called aerial bombardment of the civilian population.

Europe will experience it later in World War II.

For the painter it was a way of giving voice to his people and his message.

The press of those years was in b/w and the cinema too, except for some blockbusters with a very high budget.

In order to spread and raise funds for the Republican side (Defenders of democracy), against the Nationals (Franco dictatorship).

He presented his work at the Universal Exhibition in Paris in 1937.

Obtaining recognition and impact at a global level.

Those pioneers of graphic journalism of the time, in a photograph of the painting in b/w or without color.

They managed to convey the message of the painting to their readers, and after the passing of the years, it still retains the strength of its original genesis.

Whoever you are and regardless of who you are.

Thanks for your comment Cris! I think you have nicely summarised Picasso’s intentions with Guernica and the impact it had on the audience with this comment.

I admit I could have given more focus on Picasso’s sentiment towards the war, which naturally needs to be taken into account in any analysis of Guernica. I mentioned it in passing at the end of the Review section, but I should have probably elaborated on it.

I fully acknowledge Guernica’s potentiality as an anti-war symbol and this, by itself, is noteworthy; it is in fact one of the aspects of the painting that fascinates me. Unfortunately, reviewing the work as a whole, I do not think the quality of the painting is on par with the message it embodies.

lacklustre?

Inspired to inspire your deadclock imagine

Hi Cris. Yes, perhaps “lacklustre” was a poor choice of a word. But I was refering to the visual elements of the mural. To me, they simply don’t do justice to the intrinsic message of the painting, which I find profound.

However, art is subjective, and my opinion is really just that, an opinion. I tend to lean more towards classical art than abstract/cubist art, and my article likely reflects this inclination.