This post is comprised of different sections

Take a look at our review of Hegel’s Holiday!

Learn more about Hegelian dialectic! Or check out the full explanation Hegel’s Holiday Explained!

This post is comprised of different sections

Take a look at our review of Hegel’s Holiday!

Learn more about Hegelian dialectic! Or check out the full explanation Hegel’s Holiday Explained!

Artist: René Magritte

Year: 1958

Medium: Oil on canvas

Location: Private coleccion

Dimensions: 61 cm x 50 cm

Original Title: Les vacances de Hegel

Our rating

Your rating

I’ve been dreading the day I’d have to discuss Hegel’s philosophy.

Well, with Hegel’s Holiday, that day has come!

It should be obvious with this introduction that I’m no big fan of Hegel’s writings. But who is anyway???

Just to be clear, I’m not questioning Hegel’s genius in whatever he had to say. I don’t even doubt his exceptional skills as a writer, orator and educator.

But – and this is a big but – if you have something important to say that you wish commoners to understand and take seriously, isn’t it for your best interest to make it accessible?!?

Hegel apparently didn’t think so. His works are so, so obscure, so hard to decode, so boring, so … arghhhh… extremely frustrating to read!

You see, Hegel’s texts are so inaccessible that even nowadays experts do not seem to come to a consensus on the messages he was trying to get across.

And that was pretty clear when I set my mind on learning Hegel’s philosophy. I searched and looked everywhere: youtube videos, lectures, books, podcasts, you name it. But, at the end of the way, I realised that his texts have been interpreted differently by different scholars.

Granted, I’m no philosopher (and one could argue even not very intelligent), but come on…, why would someone write something supposedly important in such cryptic language for it to be likely misunderstood, is simply beyond me.

So, there you have it! I wanted to rant on a bit about Hegel (as if there wasn’t enough of that around) and get it all out of my system before embarking on the epic adventure (or is it more like a ride to hell?) that will be learning Hegel’s philosophy.

Hegel’s holiday is a painting by Belgian surrealist painter Rene Magritte. This relatively simple painting shows a glass filled with water standing on top of an open umbrella on a reddish background.

Frankly, I wouldn’t call Hegel’s holiday a superb work of art. Amusing, yes, but not so much a grandiose achievement. And I believe that wasn’t Magritte’s purpose with this painting anyway.

Technically, the painting is neither peculiar nor spectacular. It’s clean, nicely finished and accurate. The background has a dull, monotonous reddish colour, and the two objects represented are ordinary and uninteresting.

Even though the reflection of the glass, as well as the shadows on the umbrella panel, suggest the presence of some light source, there are no shadows being cast on the wall. So, overall, the painting looks quite static and has the feeling of being more like a postcard than an actual painting.

The title Hegel’s Holiday naturally hints at the work of the philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, who is notoriously famous for writing unduly complicated texts.

Magritte was a huge fan of Hegel, and grasping Hegel’s philosophy at a time when the Internet did not exist, is, by itself, a tremendous achievement for someone who hadn’t been formally educated in Philosophy.

Magritte probably spent days, weeks, months reading the original texts (yuck!) of Hegel’s most famous works.

Respect!

The title of the painting is subtle but clever. As a philosophy buff and a huge admirer of Hegel, Magritte most probably excelled in the readings of the German’s philosophy texts.

Being equipped with a deep understanding of Hegel, and with creativity on his side, Magritte was able to, once again (see our analysis of Not to Be Reproduced, also by Rene Magritte), encourage viewers to feel the mystery.

Our star rating is heavily weighted towards the fact that Magritte chose Hegel, out of all philosophers, as an inspiration for this work. This was a decidedly brave decision, considering how incredibly unfathomable Hegel’s philosophy is.

So, here, at Mindlybiz, Hegel’s Holiday gets a star rating of 2.5.

Well, it’s a picture of a glass on top of an open umbrella. An odd pairing of objects for sure, but not weird in the sense that you struggle to understand what you are viewing.

Magritte even discloses the idea behind the conception of this work, as the letter to his friend and critic Suzi Gablik makes clear (see below).

For those reasons, Hegel’s holiday gets a Bizarrometer score of 1.

The title should be a dead giveaway.

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel was a philosopher of the XVIII century who earned the reputation for being one of the hardest philosophers to read. Hegel is infamous for writing overly complicated texts that probably no one but himself would be able to fully decode.

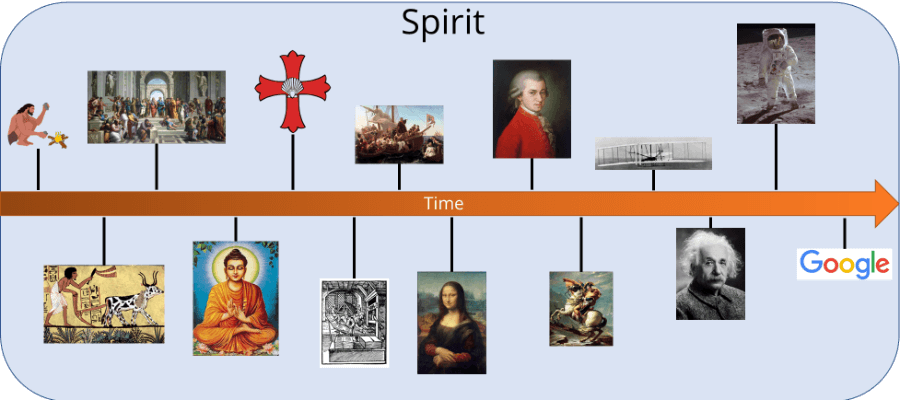

In a nutshell, Hegel noticed that the world was always in a constant flux and in a state of development and progress (e.g., 2.5 million years ago humans lived in caves, 10000 years ago we invented agriculture, and today we are able to build rockets to probe outer space).

Hegel believed that every idea had a logical contradiction of that idea. It was the tension between the original idea and its contradiction that promoted change, which could then elevate the original idea to a higher level.

Over the course of human history, humanity has been faced with ideas and their contradictions, and their sublation has, according to Hegel, brought us closer to the Absolute Truth (or Spirit, or Knowledge, or God – there are many names for it).

This is Hegelian dialectic in action – a system that opposes an idea with its contradiction, and which has the end objective to refine the original idea.

Science is a perfect example of this dialectic process in action. A researcher specifies an hypothesis about a particular phenomenon, runs an experiment, looks at the results, and sees if the results contradict the hypothesis. If they do, then the researcher updates his theory on the basis of previous findings. With each new iteration, the researcher gets a step closer to the truth about that phenomenon.

For Hegel, this dialectic process happens everywhere and all the time, ever since humanity exists. I gave the example with science above, but dialectics, according to Hegel, occurs in the realm of ideas, which brings me back to Magritte’s painting.

An umbrella is an object that repels water, whereas the glass is an object that admits water. The seemingly contradictory functions of the objects is supposed to be a tribute to Hegelian dialectics.

OK, great, but why is Hegel on holiday?

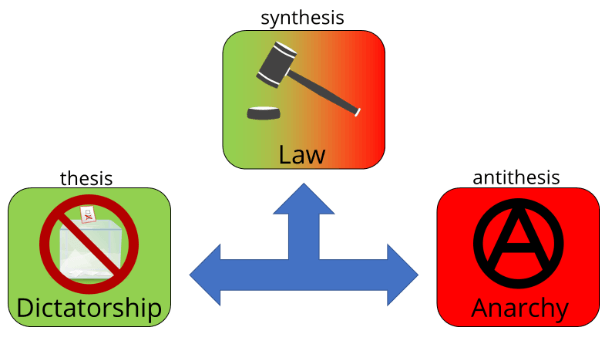

Well, if you think about it, an umbrella and a glass are not really contradictory, are they? When Hegel speaks of contradiction, he meant a literal contradiction. For example, a country might be ruled by a dictatorship, and the need for freedom might motivate the people to get rid of any form of government (i.e., anarchy). But by combining elements of both, we reach law and democracy (see the section below for additional examples of Hegelian dialectic in practice).

But the objects in Hegel’s Holiday, the umbrella and the glass, serve completely different functions. They are not contradictory. At most, we are seeing a contrast between objects, they might, in fact, be complementary.

And that is the reason why Hegel is on holiday. No need for a painstakingly analysis of logic, no need for proofs and demonstrations, no need for lengthy debates. The only purpose of this painting is for the amusement of the viewer.

According to Hegel, all phenomena (e.g., consciousness, political institutions, tradition, culture, etc) are all aspects of an entity that he calls Spirit (Geist in German).

As I understand it, Spirit is essentially the sum of everything that has to do with humanity, including human expressions, thoughts, desires, language, goals and so on. These are grouped under a single overarching term: ideas or mind.

To Hegel, ideas are never fixed, they are constantly changing. This is clear when you look at world history; language, science, law, social institutions, attitudes, traditions have been changing throughout the course of history.

So, what we experience as history is nothing more than Spirit moving through time, driving things forward, and keeping the world in a constant flux.

Spirit’s end goal is actualising itself. That just means that, through human activity, Spirit gradually becomes more self-conscious, it evolves into what Hegel calls the Absolute Spirit (more on that below), where things get more collective and unified.

The way Spirit self-actualises is through a process called the dialectic.

Dialectic comes from the Ancient Greek word diá which means “through” and lektikós, which means good at speaking, able to speak, the art of speaking. So, putting together diá and lektikós gives us more or less this translation: (something can be attained) via the ability to speak well”.

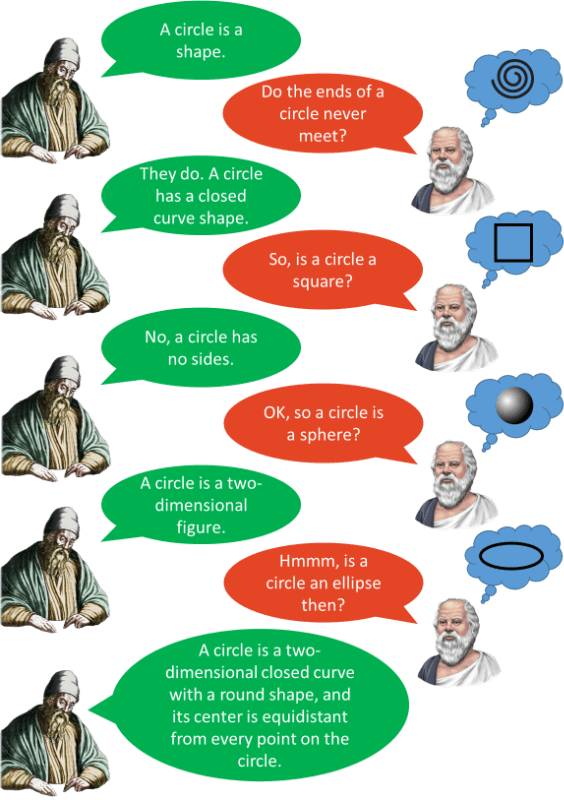

Dialectics had already been in use since Plato. Plato believed that people could achieve knowledge by engaging in conversations. He exemplifies his dialectic method by imagining Socrates asking a series of methodical questions to his interlocutors, mostly pointing out any flaws or incongruities in their reasoning. Socrates’ oppositions are an attempt to establish the truth on the topic being discussed.

So, the dialectic is really just a method in which ideas are opposed to each other, with the aim to gain truer knowledge.

Hegel’s dialectic is shaped around the idea that everything that exists, including an object, a person, a consciousness, a government, an idea, contains within itself a contradiction (or negation).

Think of a contradiction as an action or an idea that causes the original object to transform itself.

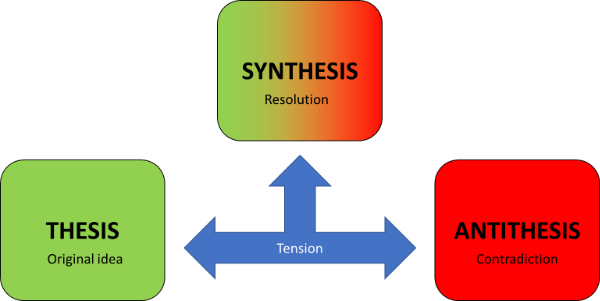

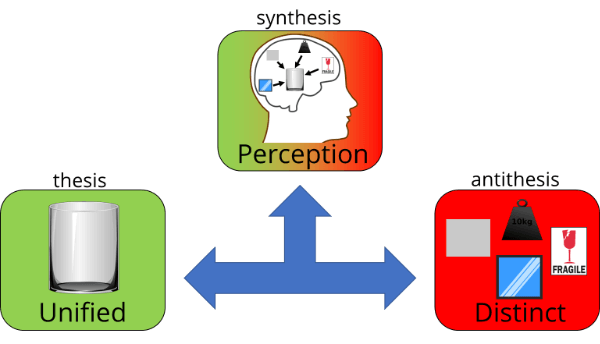

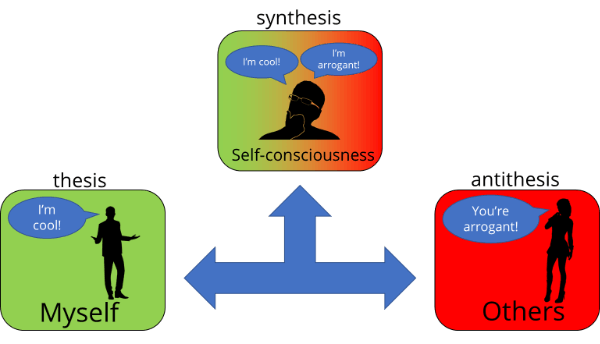

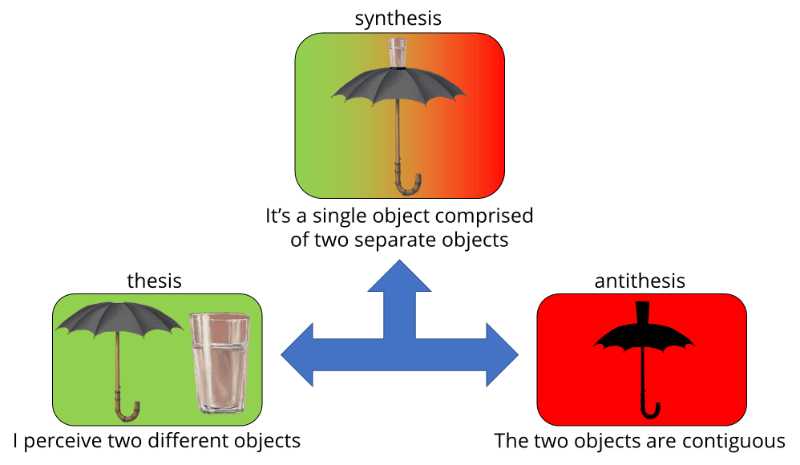

Hegel’s logic starts with two notions that are mutually incompatible. For every notion (or thesis) there is a contradiction (an antithesis). The tension between thesis and antithesis is resolved by the emergence of a higher-level stage (synthesis – Aufhebung or sublation).

Note that the antithesis doesn’t necessarily need to be the exact opposite of a thesis – it just needs to put the thesis into question. Hegel believed that it usually takes three moves for the resolve to be found.

If you go to youtube and check Hegellian dialectic video explainers, chances are that you will come across a video lauching a tirade of criticism against the use of the thesis-antithesis-synthesis triad as an explanation for Hegel’s dialectic.

It’s true that Hegel never used that formulation to describe his dialectical method. The thesis-antithesis-synthesis triad was originally proposed by Immanuel Kant and further refined by Johann Gottlieb Fichte and Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling.

Critics might evoke several reasons such as the meaning of the word synthesis bringing to mind the idea of combining or mixing things together. Hegel was careful to point out that the end result of his dialectical method is not a compromise of two things, or even their merging. Rather, the end result should be something greater, something that is elevated above and beyond the original notions.

Fair enough. However, Hegel’s ideas are already pretty complicated as they are, and opened to interpretation. Therefore, I don’t see the issue in trying to simplify some of these concepts, as long as we are aware of the limitations of using such nomencleture.

Frankly, I have yet to see a better explanation of Hegellian dialectic that does not employ the use of the thesis-antithesis-synthesis triad.

In fact, Hegel’s pundits often use terms such as Abstract-Negative-Concrete, which, in my opinion, are not only completely non-intuitive and vague, but you could even argue that using these terms is just as debatable. Hegel wrote in German, and the German words he used were “die abstrakte/verständige” (abstract/understand), “die dialektische/negativ-vernünftige” (dialectic/negative reason), “die spekulative/positiv-vernünftige” (speculative/positive reason), for Abstract, Negative, and Concrete, respectively.

So, unless a compelling argument can be made for employing particular English words as opposed to others, I believe we are caught up in semantics, which, for a newbie in Hegellian philosophy like myself, is a deterrent to the understanding.

Also, making sense of Hegel’s texts likely requires a PhD in Philosophy. But for the rest of us, we can surely benefit from the thesis-antithesis-synthesis idea, which has proven to be a good heuristic for learning Hegel’s dialectic, and also the preferred method of teaching Hegellian dialectic by reputable scholars.

Hegellian purists might completely disagree with me but, in my opinion, if the thesis-antithesis-synthesis triad not only provides a more intutive grasp of the Hegellian dialectic, but also proves to be didactically superior, then I think it’s only reasonable to make use of it.

It’s important to remember that the dialectics does not happen on an occasional and disjointed basis.

In fact, it takes place all the time whenever two objects (and by that I mean two ideas within an individual, two individuals, an individual and a rock, two institutions, two religions, etc) interact and create tension.

And when a synthesis is generated, it becomes the new thesis which gets contradicted and develops into a synthesis and so on and so forth.

Note that the original thesis and antithesis are not destroyed. Rather, these oppositions are preserved at a higher level. Indeed, when sublation is successful, two things occur: negation and preservation. The tension between opposites is both negated and preserved. It has a partial truth to it which exists within the superseded notion.

It’s important to realise that the synthesis isn’t simply mutating things together. It’s not like we are trying to find a compromise between a thing and its opposite (by the way, I believe this is the reason why people often avoid talking about a synthesis-antithesis-synthesis when discussing Hegel).

So, we are not looking for a compromise. When we start with a notion (thesis), apply a contradiction (antithesis), the resulting notion (synthesis) should be an elevated form of the original notion.

In addition, the synthesis is not something from the outside that resolves the apparent contradiction. The synthesis emerges from the original notion and its contradiction, so it is really one aspect of a three-part notion (thesis-antithesis-synthesis). That means that old notions have the potentiality already in them, and the synthesis is simply the actualisation of that potentiality.

Likewise, the contradiction of the idea is internal to the original idea itself. To illustrate this, think of the concept of freedom. Few people would disagree that freedom is essential and should be pursued by every human being. However, even freedom can be abused, as in the case of land/business owners calling upon their “freedom” to exploit and oppress their employees. So freedom has within itself a contradiction – oppression.

The successful transformation of a seed to an oak tree requires several factors such as sunlight, water, and adequate soil. However, if the seed is not yet ready to contradict (or transform) itself, it will remain a seed, regardless of the conditions in its environment. So, the transformation (contradiction) of the seed is totally internal to the seed, and not due to external factors – this is what Hegel means by everything that exists is contradictory in itself.

Unfortunately, practical examples of Hegel’s dialectics are relatively scarce. But I like to work with practical examples, so I’ll give my best shot.

Let’s think of the case of a dictatorship (thesis). People are often discontent with this kind of government, so it generates the need for freedom. The dictatorship could get opposed by a form of government with total political freedom – anarchy (antithesis). Now, if you combine an element of dictatorship with an element of anarchy you create law and a democratic government (synthesis), which is, by most accounts, a superior form of government.

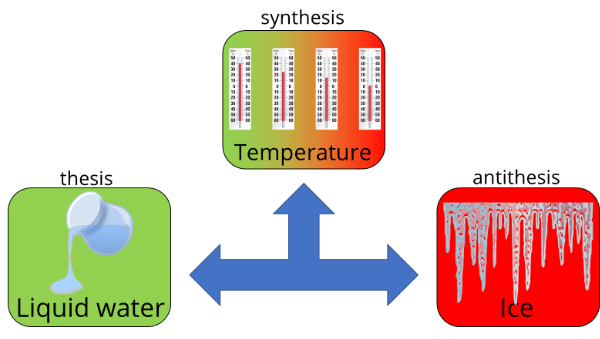

Let’s say you run an experiment and the results tell you that water is a liquid (thesis). However, additional experimentation reveals that water can be solid as well (antithesis). By reasoning (combining elements of both the thesis and antithesis), you reach the conclusion that water can be both liquid and solid, depending on the temperature (synthesis). So, based on observation and experimentation, you reached a conclusion that is more accurate.

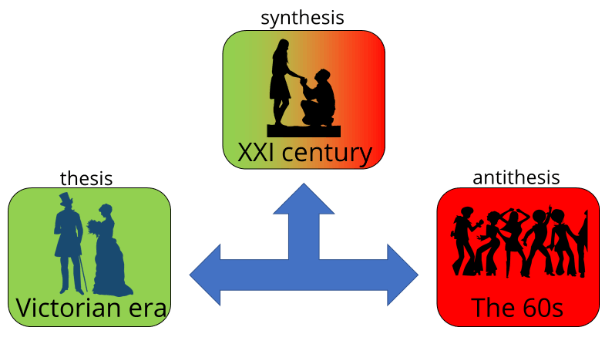

The Victorian era was famous for its puritanical and repressive attitude towards sexuality (thesis). This led to a natural increase in sexual freedom, which resulted in the extreme liberal stance on sex of the 1960s (antithesis). A balance has been restored in our current decade (synthesis), since we now have sexual freedom but (most of us) restrict its use to intimate settings.

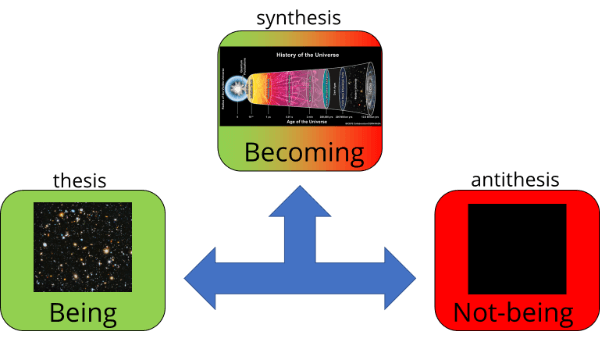

Hegel put forth the notion of “being” (thesis). This concept however contains a contradiction, because something that exists will not exist and has not existed forever. So, to grasp the notion of being requires the idea of nothingness, or not-being (antithesis). How is this contradiction resolved? The concepts of “being” and “not-being” are two aspects of a superseded concept: becoming. That is, the state of “not-being” moves to (or becomes) a state of “being”.

When I see a glass on a table, I perceive the glass in its entirety, as a single entity (thesis). However, my wife points out that the glass isn’t a unified object. It actually contains different properties such as shape, colour, transparency, weight, texture and so on (antithesis). True, but despite the many properties of the glass, our human brain is hardwired to perceive the glass as one single entity (synthesis).

Let’s say I feel like I’m a very confident person (thesis). However, I interact with other people in this world, and they will have formed an opinion about myself, maybe that I’m arrogant (antithesis). So, in order to gain a better understanding of myself, I should try to see how others see me, without, of course, loosing sight of what I think about myself. If I allow this tension to play out (the tension between what I believe I am, and how others see me), it’s just possible that I’ll become closer to understand who I’m truly are, and reach self-consciousness (synthesis).

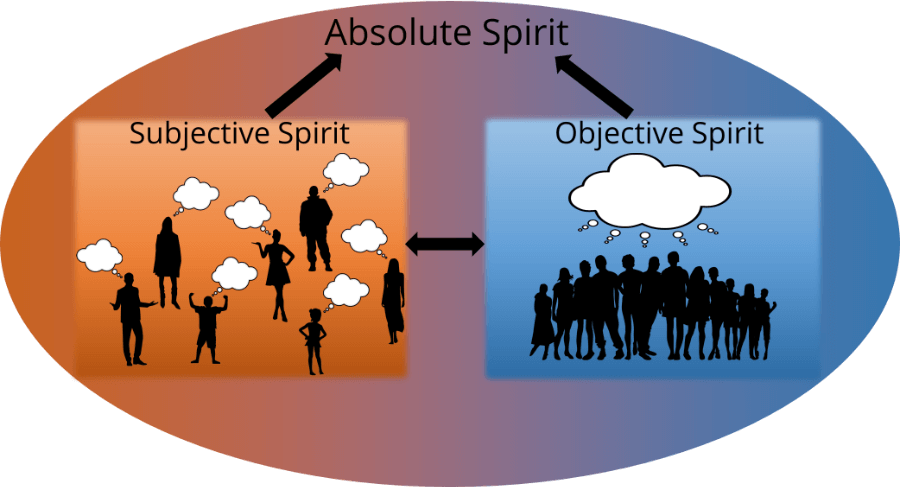

The dialectic begins with individuals gaining self-consciousness, that is, being aware of himself/herself as an individual among other people (see example 5 above). This is Subjective Spirit, according to Hegel, and happens within the mind of an individual (hence subjective).

You can think of subjective Spirit as the individual interests, desires and objectives in life. When you try to fulfill those desires and goals you are contributing to the self-actualisation of Spirit

The dialectic evolves to encompass the consciousness of social and political groups, tradition and culture. Hegel calls this the Objective Spirit.

The objective Spirit is, thus, ideas that are shared among all people. For example, humans seem to possess concepts such as tradition, culture and society, regardless of the environment they were brought in. As such, tradition, culture and society are all aspects of the Objective Spirit.

And it is objective Spirit (ideas shared among people) that end up shaping our own individual perception of reality. Thus, we interact and engage with the world around us through ideas that are shared among human beings (i.e., objective Spirit).

To Hegel, the dialectical process on both the Subjective and Objective Spirit continues in this way, always refining itself, with the aim to reach an end point. That end point is the Absolute Spirit, the reconciliation of Subjective with Objective Spirit (the totality).

The Absolute Spirit is a kind of consciousness that belongs to reality as a whole (and not to any single individual). When Spirit reaches this stage, we can say that knowledge is complete. I believe this means that humanity reached a sort of nirvana, where societies flourish in peace and humans behave completely rationally.

If there is something that drives me mad is the sort of tricky phrases that explain concepts in riddles. Why really?!?

For a long time, the phrase negation of a negation looked like one of them, but I will try to break it down and show it to you that it isn’t really that bad (provided, of course, I’m getting the concept right myself).

To explain what the negation of a negation in Hegel’s philosophy means, let me give you an example using science (thanks to Alison Adams, for a great explanation here).

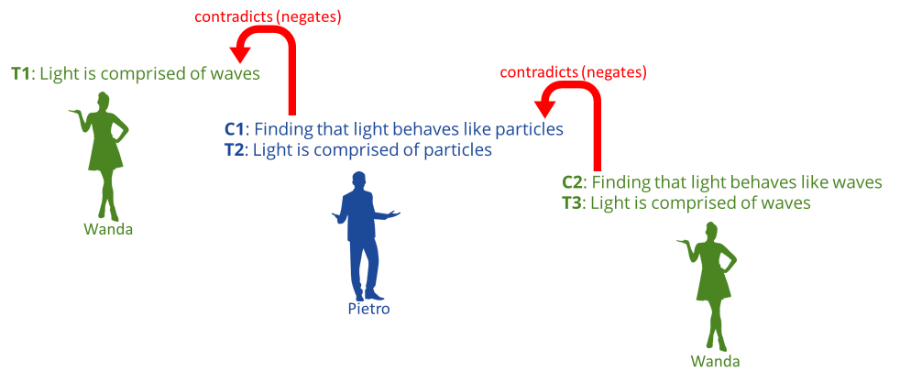

The way science develops is through a continual dialectic: scientists come up with a reasonable theory (thesis), which is confronted with a contradiction (antithesis), that results in a new theory (synthesis). That theory (now itself a thesis) gets contradicted again (antithesis), creating a new theory (synthesis) and so on and so forth.

Hegel’s fabulous insight was that these contradictions do not simply update the original ideas; contradictions are actually the agent that allow the original ideas to develop into a higher level.

Imagine that a scientist called Wanda has a hunch that light is comprised of waves. Let’s call that theory 1 (or T1).

Then, another scientist, Pietro, carries out an experiment and finds that light behaves like tiny particles, and so, this finding contradicts T1 (let’s call that contradiction C1). So, Pietro proposes a new theory that states that light is made of tiny particles instead (T2).

However, Wanda decides to devise an experiment herself, which turns out to contradict the idea that light behaves like particles (this is C2). Then, she revives her previous theory that suggests that light really behaves like waves (T3).

So, one could conclude that T1 = T3 since they both claim that light consists of waves. If so, we should also conclude that if C1 contradicts T1, then C1 should also contradict T3 (since T1 and T3 are equivalent). This means you could simply apply C1 to whatever further claim that light behaves like waves.

But that clearly won’t work. C1 was already contradicted by C2, and, thus, C1 does not have the potential to modify the state of T3.

So what is going on here? What makes T1 and T3 different?

They differ in that T3 is the result of a historical progress. T3 contains in itself a history, in which C1 and C2 became parts of it. T1 does not have this history, and that is the key.

This is actually very relevant in my example. Light can actually behave both as a wave and as a particle, depending on the experimental set-up you use to detect it.

T3 has synthethised all the previous findings, so Wanda can forge a new theory that suggests that light can behave both like particles or like waves, depending on the type of experiment that is carried out.

In other words, T3 contains both thesis (T1 and T2) and antithesis (C1 and C2) and incorporates that information, that history, into itself, whereas T1 does not. That is the difference between T1 and T3.

Now we are in a good position to understand what a negation of a negation means.

Remember that C1 (the finding that light does not behave like a wave) is the negation of T1 (the theory that proposes that light behaves like a wave). On the other hand, C2 (the finding that proves that light behaves like a wave) is the logical negation of C1 (the finding that light does not behave like a wave).

So, if C2 is the negation of C1, and C1 is the negation of T1, then C2 is a negation of a negation.

C2 (which leads to T3) is essentially the synthesis of this whole story. So, the synthesis is the negation of a negation.

Pheeww…

OK, that’s enough of Hegel for today (and probably for years to come)!

If you read the previous section of Hegel’s philosophy, thinking that this analysis will be indeed very deep, I’m afraid I will have to disappoint you.

This is because Magritte did not employ the sort of rigorous logic demonstrations that any philosopher would readily go through.

To see why, here’s a letter written by Magritte to the art critic Suzi Gablik explaining the origin of the painting:

My latest painting began with the question: how to show a glass of water in a painting in such a way that it would not be indifferent? Or whimsical, or arbitrary, or weak – but, allow us to use the word, with genius? (Without false modesty.) I began by drawing many glasses of water, always with a linear mark on the glass. This line, after the 100th or 150th drawing, widened out and finally took the form of an umbrella. The umbrella was then put into the glass, and to conclude, underneath the glass. Which is the exact solution to the initial question: how to paint a glass of water with genius. I then thought that Hegel (another genius) would have been very sensitive to this object which has two opposing functions: at the same time not to admit any water (repelling it) and to admit it (containing it). He would have been delighted, I think, or amused (as on vacation), and I call the painting Hegel’s Holiday.

René Magritte

According to Hegel, every object is contradictory in itself. Every idea presupposes a tripartite division which involves the formation of a thesis, its antithesis and the resulting synthesis.

A simplistic reading of this painting could be that the two objects are a kind of negation of a negation (check out the section Negation of a negation). The umbrella is negating water (by repelling it), whereas the glass is negating the function of the umbrella (which is negating water).

So, you could think of the function of the glass as a negation of the negation, which is often interpreted as the synthesis in the context of the thesis-antithesis-synthesis triad.

But should we really think of the glass as a synthesis? Synthesis of what? What is the original idea that forms the thesis? Naively, we could think of the umbrella as a thesis. But if so, what is the contradiction, or antithesis? And even if an antithesis were formulated, why would a glass be the synthesis of the original idea, which is the umbrella?

Remember, the synthesis should incorporate the original idea, and elevate it to a higher stage of development.

These type of questions are the reason that the title reads Hegel’s Holiday and not Hegel’s at Work. Hegel would have find the painting of objects having contrasting functions amusing, but surely not worthy of a serious philosophical analysis.

That’s the reason why most analysis of this work refer to the two objects as contrasts, rather than contradictions. The umbrella that repels water is contrasted with the glass that admits water.

Fair enough. But let’s dissect this painting a little further.

You see, my initial mistake when I first looked at this painting was assuming that I was looking at two different objects: 1) a glass of water and 2) an umbrella.

But in Magritte’s letter to critic Suzi Gablik he writes: “I then thought that Hegel (another genius) would have been very sensitive to this object which has two opposing functions: at the same time not to admit any water (repelling it) and to admit it (containing it).”

I emphasised Magritte’s usage of the word “this object”, so that you notice that he is not referring to the umbrella and glass as two separate objects. He’s referring to the contents of the painting as an “object which has two opposing functions”.

So, the painting depicts an object which looks like a glass on top of an umbrella, an umbrella-glass object, if you like.

We established above that there is no contradiction really. The glass is not contradicting the function of the umbrella.

In fact, the composite object, which consists of an object (glass) which function is to admit water, and an object (the umbrella) which function is to repel water, is not contradictory. It’s actually complementary, and could, thus, be viewed as a synthesised object.

So, let’s go down a different route, and think how Hegel’s idea of contradiction can be applied to this synthesised object.

People look at Hegel’s Holiday and see two objects: a glass and an umbrella. You see two objects because they look dissimilar, and your daily experience with these objects tells you that they serve different purposes.

So that can be your thesis: “I perceive two different objects with contrasting functions”.

However, one could argue that maybe this is an artwork, maybe the two objects are supposed to be contiguous in space, meaning that they are really one single object – that would be the antithesis.

In fact, even though they are clearly two distinct objects, they are actually comprise one single entity (an umbrella-glass object), which provides two functions: repel and contain water. We have reached our synthesis (this is similar to Example 4 – Abstract ideas I mentioned above).

Note how this idea adheres to Hegel’s logic (check the section Spirit and the Hegelian dialectic):

1) we have an initial notion (they are two distinct objects) and its contradiction (they are one single object)

2) the contradiction is a logical negation of the initial notion

3) the synthesis (the umbrella-glass is both one and many) resolves the contradiction and elevates the original notion.

Now you say, “Ahhhh, why would we need such a thing as an umbrella-glass. That’s all made up!”

Yes, of course it’s made up. Still, the point I’m trying to convey is that any notion has a contradiction that is inherent to itself (in this case, that it is a single object, but also multiple objects), and this can be resolved by proper analysis of the initial notion.

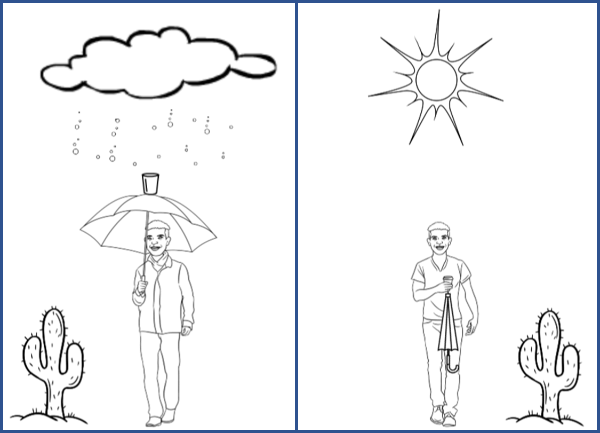

One could even rationalise the reason one might need an umbrella-glass object (other than for the purpose of art).

Imagine a situation in which someone is lost in the desert. Let’s also pretend that that someone has a condition in which his skin is extremely sensitive to water. However, he is still human and needs to drink water to survive. He sights far away a rare agglomeration of clouds forming, and he in a conundrum: there is nowhere to take cover, but when it rains, he doesn’t want the water to pour down on him. However, this will probably be her last chance to collect water to survive.

Fortunately, he had forestalled her problem and brought along his unfailing umbrella-glass object: he takes cover under the umbrella, and the glass placed on top of the umbrella collects the water, which he drinks once the rain stops.

Of course, this is a silly example, but consider that if this idea was indeed useful, it would become part of our culture, part of world history. Perhaps even play a significant role in the development devices that, in the far future, could have a greater impact in the history of mankind.

Spirit manifests itself even in the smallest of ideas, because, ultimately, everything is connected through the dialectical process.

And this is what the Hegel’s dialectic is all about: elevating ideas above and beyond their original notions by use of contradictions and towards the ultimate goal of Absolute Knowledge.

Together with The Treachery of Images (the famous “this is not a pipe” painting), Hegel’s Holiday is one of the “entertaining” works by Magritte.

He imagined meeting with Hegel and showing him this painting, which Magritte believed would amuse the philosopher.

Hegel was famous for his dialectical method, which, simply put, deals with the constant contradiction of an idea, with the aim to reach truer knowledge.

But even though Magritte was an avid reader of Hegel, I don’t think he devoted an awful lot of time in logic analysis. In contrast to other Magritte paintings (e.g., Not to Be Reproduced), Hegel’s Holiday was meant to be humorous, rather than philosophical.

And so, keeping in line with the theme of the painting, I put forth a rather whimsical (if not silly) interpretation of Hegel’s Holiday in the context of the Hegellian dialectical method. Despite our experience telling us that the umbrella and glass are two separate objects with contrasting functions, they actually form a single entity (an umbrella-glass object), which could be thought of as a synthesised idea.

I think Hegel would have definitely enjoyed his holiday!

If, by any chance, I gave the impression of being dismissive of Hegel’s work, it couldn’t be further from the truth.

I actually think Hegel had a phenomenal insight with this idea of humans being inherently historical and that the progression of history is nothing more than the panning out of an extremely complex interaction of ideas (i.e., the dialectical process).

I have to admit though that in trying to understand Hegel I feel like it took a toll on my brain cells, so it might take a while to recover… 😀

See you in the next article!

Leave a comment

Add Your Recommendations

Popular Tags