This post is comprised of different sections

Take a look at our review of Not to Be Reproduced!

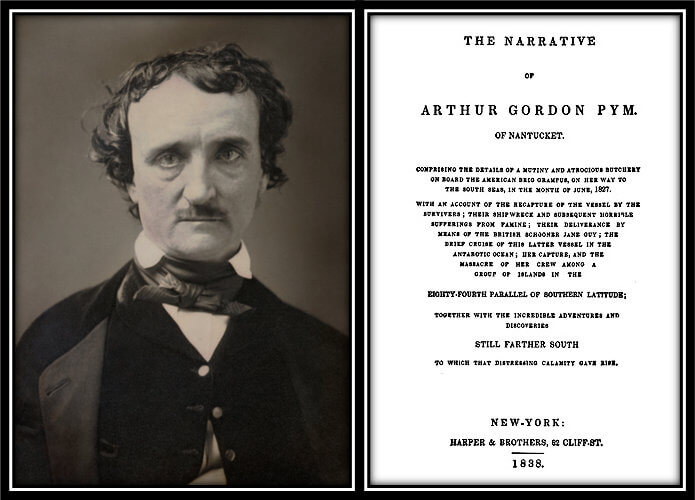

Learn more about Edgar Allan Poe’s "The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket"!

This post is comprised of different sections

Take a look at our review of Not to Be Reproduced!

Learn more about Edgar Allan Poe’s "The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket"!

Artist: René Magritte

Year: 1937

Medium: Oil on canvas

Location: Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, Netherlands

Dimensions: 81.3 cm x 65 cm

Our rating

Your rating

Very few would disagree with the statement that René Magritte was one of the most talented and peculiar surrealistic painters that ever existed.

Magritte was a painter:

Magritte was a philosopher:

You can wonder about what is imagined and what is real. Is it about the reality of appearances or the appearance of reality? What really is inside, and what is outside? What do we have here: reality, or a dream? If a dream is a revelation of waking life, waking life is also a revelation of a dream.

René Magritte

Magritte was a poet:

The function of painting is to make poetry visible.

René Magritte

A painter, a poet and a philosopher – what a combo!

I dare say that Magritte’s paintings lack the vivacity of a Dali or the drama of a Max Ernst, but they are surely the more philosophical of the bunch.

Luckily, this alone, gives me plenty of material to analyse :).

Not to Be Reproduced is one of my favourite paintings by Magritte, and will be the topic of the present article.

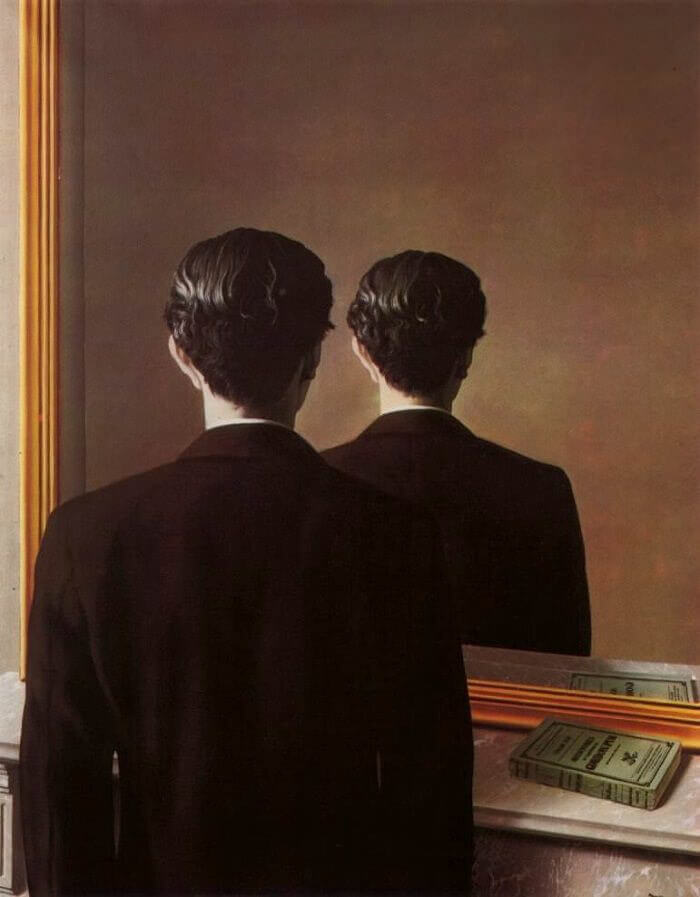

Not to Be Reproduced (original title: La reproduction interdite) is a 1937 oil painting by Belgium artist René Magritte.

It shows a man standing and looking into a mirror. Contrary to our expectation, the image in the mirror shows the reflection of the man’s back, as opposed to the frontal part of his body and his face.

The man depicted is likely British poet Edward James, who commissioned the work from Magritte.

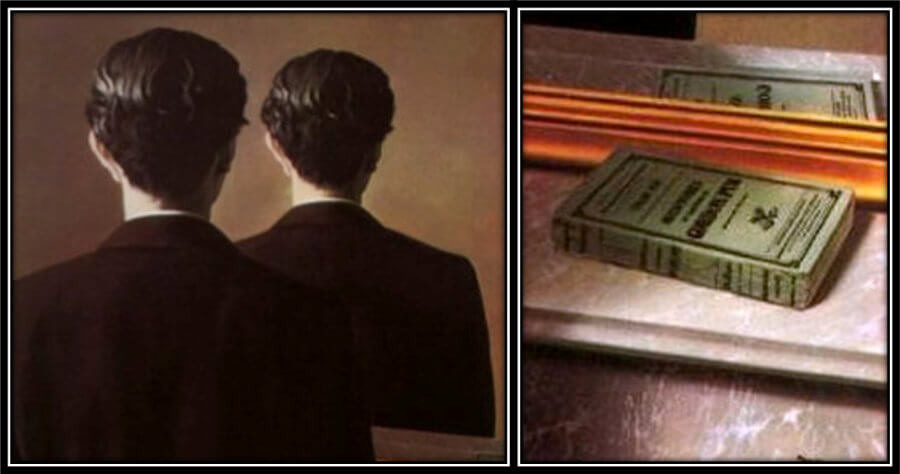

A French copy of the book The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket (Les aventures d’Arthur Gordon Pym) by Edgar Allan Poe is visible on the mantelpiece on the lower right corner. Contrary to the man’s reflection, the reflection of the book in the mirror is correct.

Behind the reflection of the man we see a bland brown/dark orange wall, which takes up about half the painting. It is probably a reflection, suggesting that the room in which the man is in is mostly empty.

An interesting aspect of this painting is that even though the man’s reflection is clearly impossible within our physical world, there are other elements that mimic reality as we know it (e.g., the correct reflection of the book in the mirror).

Magritte reveled in such contradictions because they confronted viewers with two incompatible manifestations, forcing viewers to face this contradiction and reflect upon it (see also our article on Hegel’s Holiday).

As we will see, this has very much in common with the story of the novel on the mantelpiece, which, in my opinion, plays a much central role in the meaning of the painting than most analyses I read appear to suggest.

I find the execution of this painting formidable. Look closely how well Magritte applied contrast to make the hair look shiniest closest to the light source; how the man’s shadow covers half of the book, which is also surgically reflected on its reflection in the mirror; how the creases of the man’s suit jacket are carefully positioned; how the marmoreal polish of the fireplace looks almost photographic.

The ambiguity of the painting causes a slight discomfort in the viewer. One expects to see the frontal part of the body and the face, but is presented instead with a duplicate of the man’s back. This ambiguity, coupled Magritte’s use of dull colours and largely empty room, gives this painting a slight sinister look.

And let’s be honest. Not to Be Reproduced isn’t lavish. You could even argue that it is ordinary and static.

But making flamboyant art was never Magritte’s aim as an artist. Being the philosopher and the poet he was, Magritte attached more importance to the thought process.

For Magritte, painting should reflect what goes on in the mind, rather than what the physical eye saw, and, thus, he encouraged the viewer to look beyond the visual representation of objects.

Out of all Magritte’s paintings, I find Not to Be Reproduced among the most technically impressive. Despite the monotonous colours and mundane scene, the brushstrokes are so masterfully executed that it borders photorealism.

But Magritte wasn’t content with painting for the sake of painting. Mystery was paramount to him, and I believe Not to Be Reproduced really delivers just that.

Not to Be Reproduced gets a star rating of 4.

Of course, being a surrealistic painting, Not to Be Reproduced most certainly contains a fair amount of weirdness. However, as most surrealistic works by Magritte, it is not awfuly bizarre.

The discomfort we may feel when viewing this work will likely be due to the thwarted expectation to see the appropriate reflection of the man in the mirror, rather than the bizarre elements per se.

Furthermore, the meaning of the painting seems fairly clear (read on our analysis below).

For these reasons, Not to be reproduced gets a bizarrometer score of 3.5.

Paintings are the representations of the subjects from the perspective of the artist. What we believe we are seeing may or may not be the truth as the artist intended.

And that is not a bad thing – the ambiguity is what envelops paintings with mystery, allowing your imagination to kick in.

I believe this point is critical in understanding Magritte’s painting.

Not to Be Reproduced confronts us with two opposing realities: the incorrect reflection of the man vs. the correct reflection of the book. The painting is disquieting because it fails to meet our expectation to see the face and frontal body of the man in the mirror.

With this incongruity, Magritte is calling on our capacity of contemplation and imagination. He does not want the viewers to simply look at the painting and appreciate it as it is (which we probably would, had Magritte painted an accurate reflection of the man). Instead, he wants us to reflect on the contrasting realities, and experience the mystery that the painting evokes.

By painting a reproduction of the man’s back (as opposed to a reflection) we are also forced to question what we see, to question the reality of the narrative.

This has very much to do with the idea of the unreliable narrator.

Every work of art displays a subject in terms of how the artist envisions that subject. By introducing fictional physics (the impossible reflection of the man), Magritte incorporates an unreliable narrative into this painting.

The French copy of Edgar Allan Poe’s novel The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket that stands on the mantelpiece is very pertinent to this aspect of an unreliable narrative.

The protagonist of the novel, Arthur Gordon Pym, is a prototypical unreliable narrator (click here for our analysis of Poe’s novel). Pym’s narration contains contradictions, dubious events and even a confession from him that he may be fabricating some parts of his account.

So let me start with a precis of Poe’s novel, as well as a plausible interpretation of it, which will be important when analysing Magritte’s painting later on this article.

If you haven’t done so yet, check out our article about Poe’s novel The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket, in which we analyse and provide a few interpretations of the novel.

The book starts off with a preface which was allegedly written by the protagonist of the novel, Arthur Gordon Pym himself.

Pym begins by saying that he was initially reluctant to publish his adventures, since his experiences at sea were so bizarre and outrageous that he feared readers would dismiss his account as mere fable.

Furthermore, he admits that he did not keep a diary during most of the journey, so the retelling of the events from memory might suffer from a slight exaggeration on his part. He suspects that only family and close friends would probably believe him.

Pym is also self-critical about his writing abilities, which further lessened his enthusiasm to turn his narrative public.

An editor of the magazine Southern Literary Messenger, a so-called Mr. Poe, persuades Pym to publish the work under the guise of fiction.

So, straight from the beginning, we are confronted with the possibility that Pym’s account is all but balderdash. The reader is warned about the divergence of thoughts (Pym believes it is true but admits he might be making up some of the details; Pym writes that only his friends might believe him but not the general public).

You see, Poe could have omitted the aspects that make us question Pym’s account. For example, he could have presented the story as is, without making any reference to whether people believed Pym or not. But Poe deliberately introduces ambiguity in the preface. He makes us aware of the dubious narrative that Pym has purpotedly written.

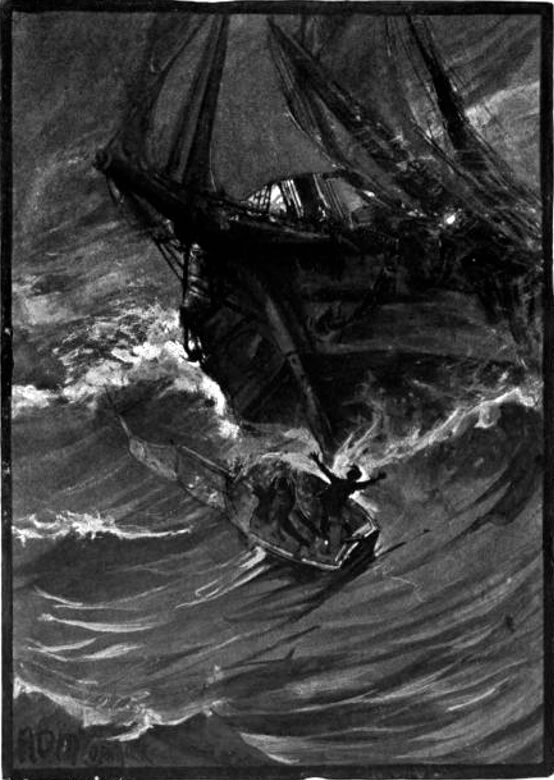

After the preface, the actual narrative starts. The first chapter tells Pym’s adventures at sea with his friend Augustus aboard Pym’s small boat “Ariel”.

Pym suffers his first nautical disaster, but is rescued by a frigate by the name of Penguin.

The preface mentions that the Ariel story was actually written by Mr. Poe, even though it is told from Pym’s first perspective narration. Once again, this superfluous information, which could just as well have been ommitted without sacrificing the narrative, has the effect of confusing the reader even more.

The next chapters deal with Pym’s (mis)adventures on board of the whaling-ship “Grampus”.

After sneaking Pym onto the ship, Augustus hides him in a hold and instructs him to remain there until the Grampus is sufficiently far away from the coast, that the captain of the ship will have no other option but to continue his journey with Pym aboard.

However, when Augustus fails to come down after a few days with provisions and water, Pym becomes delirious and almost dies of thirst and hunger.

He is saved in the nick of time by Augustus, who explains that mutiny broke out, which was the reason for not coming down earlier.

Pym forges an alliance with Augustus and another crew member called Peters, and the three men successfully quell the mutiny.

However, a violent storm severely damages the ship, eventually capsizing it. The demoralised crew face starvation, and resort to cannibalism of a fellow crew member.

Pym faces many tribulations: gruesome sightings of putrefied bodies on a passing ship; the constant surveillance of hungry sharks; and the prospect of dying from hunger and/or dehydration. Augustus dies, but Pym and Peters are eventually rescued by Jane Guy, a ship en route to the South Pole on an exploration mission.

It is worth noting that there are at least two very noticeable mistakes in Pym’s narration.

First, Pym owns a dog, Tiger, which plays a prominent role in saving Pym’s life more than once aboard the Grampus.

However, Tiger mysteriously vanishes after they put a stop to the mutiny, and Pym provides no explanation of its whereabouts.

Second, Pym writes that Augustus almost gave up on Pym when he couldn’t find him on the hold, thinking he might already be dead. Pym also writes that many years ellapsed before Augustus plucked the courage to tell Pym. Yet, Augustus dies a few weeks later while still on Grampus.

Being the experienced writer Poe was, it is indeed very strange that he would make two obvious blunders of this kind.

Perhaps Poe deliberately distorted the storyline in order to increase the ambiguity with regards to the truthfulness of Pym’s telling of the events.

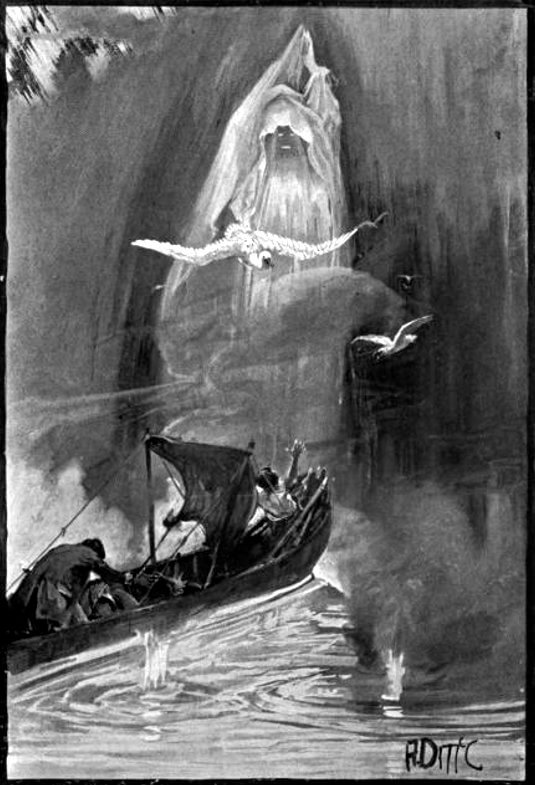

The last chapters of the book introduce us to the southern island of Tsalal and its inhabitants, a tribe of black natives that fear anything white.

Even though being initially cordial towards the crew, they eventually reveal their nefarious purpose of killing every single member of the crew.

Pym and Peters barely survive the ambush laid out by the islanders, and escape the island on a canoe with a captured native.

As they sail southwards towards the south pole, they begin to witness strange phenomena: water becomes warmer, thicker and milky white; they see strange all-white animals flying above their heads; ash puring down; a curtain of vapour rising on the southern horizon.

The novel ends abruptly, just as Pym and Peters approach a chasm and a giant human white figure emerges.

So, Pym’s account ends in such an anti-climatic and puzzling fashion that the reader feels completely baffled as to what the heck is going on.

The bizarre sightings (e.g., gigantic white animals, curtain of vapour covering the entirety of the southern horizon, huge human figure) are just so strange and displaced when considering the rest of the novel, that we feel, once again, that Pym may be making this stuff up.

In fact, there is a point when the three men (Pym, Peters and the captured native) begin to lose control of their senses and become apathetic.

There are also mentionings of dreaminess and numbness of mind as they approach the chasm, which could suggest that Pym wasn’t in full possession of his faculties.

There is a post-scriptural note ostensibly written by the editor of the book. It is explained that Pym survived his ordeal and returned safely to the US, dying in an accident later in his life.

The editor suspects that there might exist two or three chapters which would provide a closure to Pym’s tale, but they were, unfortunately, lost with him.

The editor continues saying that Peters is alive and lives in Illinois, but he is unreachable.

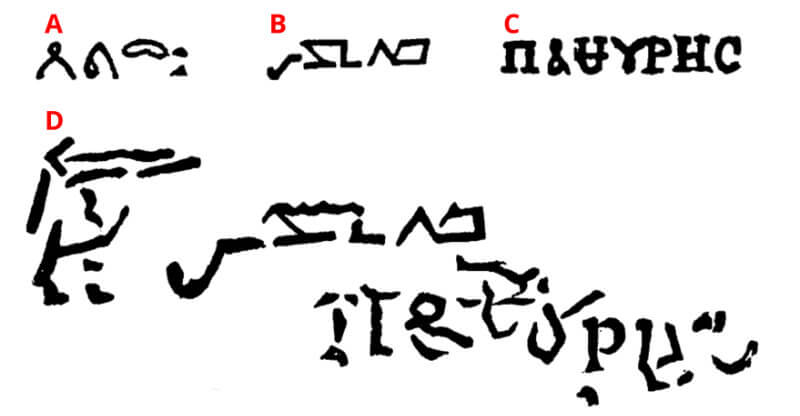

The book ends with an attempt to explain strange markings on the Tsalal rocks that Pym drew on a piece of paper, which turn out to be of African and Arabic origins (see figure above).

Once again, we are presented with more dubious information.

First, Peters is alive but unreachable?!? So, the only person that could settle, once and for all, the veracity of Pym’s account is unexplicably unavailable!!

Again, Poe could have just written that both Pym and Peters died and that would be the end of it. But, no, Peters is alive but won’t talk. Can there anything be more suspicious than that?

Also, the post-scriptural note spends a great deal of time discussing a few markings that Pym had encountered on the Tsalalian rocks and which were only secondary to the story.

Pym was convinced that the markings were the work of nature. In contrast, Peters, who happened to be around Pym when he stumbled across the rock markings, correctly believed the markings to be alphabetical characters.

Well, the editor actually sides with Peters and corrects Pym’s interpretation in the post-scriptural note.

So, once again, we have the editor of the book pointing out the inadequacy of Pym’s interpretation, making his character even less reliable.

OK, so I’ll discuss how the novel relates to Magritte’s painting shortly.

But first, let me just say that to understand Magritte’s art, it isn’t sufficient to dissect what is visually shown to us and look for clues that may guide us through the narrative of the painting.

Rather, Magritte wanted viewers to contemplate the opposing aspects of his works, and feel the mystery that the narrative naturally evokes.

The idea doesn’t matter to me: only the image counts, the inexplicable and mysterious image, since all is mystery in our life.

René Magritte

Consider the reflections of the book and the man. The reflection of the book in the mirror conforms to our expectations. In contrast, the reflection of the man violates the laws of physics, it is an impossibility – it does not reproduce the man’s reflection accurately.

Even the man himself can be thought of as two different realities: one real, truthful (the man looking into the mirror), and one imaginary, deceptive (the reflected image in the mirror).

Oppositions such as these are ubiquitous in Magritte’s art. He wished to represent the reality as it is, while, at the same time, portraying an alternate reality, and it is this conflict of realities that brings mystery into the painting.

The original title of this painting is La reproduction interdite, which in French could have two possible readings: “reproduction is prohibited” (forbidden) and “prohibited reproduction” (an impossible reproduction).

You might think that the mirror is reflecting the image of the man. If so, and setting the weirdness aside, the angle of the man’s reflection in the mirror would be different than what it actually is (I attempted to show what a more accurate “reflection” would look like in the figure above) – just as the book’s angle is different from the angle of its reflection in the mirror.

And I think the fact that the book is correctly reflected in the mirror is an important point. Magritte wasn’t being sloppy or innatentive when he painted the man, but purposefully painted an erroneous “reflection”.

This means that the “reflection” of the man isn’t supposed to be a reflection at all, but rather an exact copy (or reproduction) of the man’s back – a sort of copy-paste onto the mirror.

And there’s plenty of food for thought here, was not Magritte a philosopher. People think of image reproductions as error-free facsimiles of the actual objects they represent. But what we consider to be the truth may not always be the truth.

Appearances can be deceiving and depend on the viewer’s point of view and perspective.

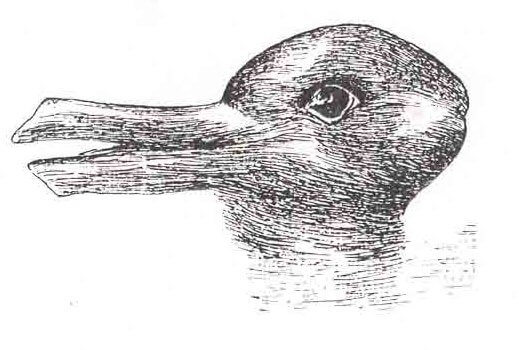

A modern example of this are visual illusions, such as the one in the figure above. What do you see? A rabbit or a duck?

In either case, you’d be correct! Whether you see a rabbit, a duck, or both, is largely dependent on psychological and sociological aspects. For instance, people are more likely to perceive a rabbit around Easter, whereas they are more likely to see a duck around fall. So, our senses can be deceived, manipulated, depending on a complex multitude of factors.

With Not to Be Reproduced, Magritte is telling us to question reality, to question our perception of images.

But then, what should you believe when you look at a piece of art? Did Magritte offer a solution to this conundrum?

Well, I believe he did. Magritte was adamant we should see with our mind’s eye, rather than the physical eyes. That is, reflect over the contents of the work, let the imagination flow and feelings surface. Feel the mystery!

Again, it’s important to stress that we should not look for the key to that mystery (that’s what sets Magritte apart from other surrealists). Instead, according to Magritte, the purpose of his art is the journey that takes you to that mystery, not what lies beyond it.

If you happen feel the mystery, then the purpose of his art has been accomplished.

Magritte’s fascination with Poe’s writings is directly evidenced by the presence of the book on the mantelpiece.

The Narrative of Arthur Pym of Nantucket is Poe’s only novel, and I was surprised that most analysis of this painting overlook it as either a mere curiosity or as Magritte’s homage to his favourite author (a curiosity: Poe’s novel was published in 1838, almost 100 years before Magritte completed Not to Be Reproduced).

However, after reading the book (you can find the analysis in our previous article), I feel that there could be a more profound link between the two works. After all, why did Magritte choose this particular book in this painting?

Magritte was a huge fan of Poe, who was immensely influential in Magritte’s thinking and work. Poe’s short stories (and novel as I described above) are full of dubious characters that call into question the veracity of their narrations.

I reviewed Poe’s book in the previous article for a reason. In fact, I was content with the interpretation that Pym had returned safe and sound to the US after meeting the giant white figure at the end of his narrative.

However, having the painting in mind, I put forth another, different interpretation – that Pym constitutes a prototypical unreliable narrator.

Take the preface of the novel. It was allegedly written by Pym himself (the protagonist of the novel). Pym stresses that he is the actual author of the book and not certain Mr. Poe, who is actually the editor of the work. Pym explains that he initially did not want to make his adventures public; he thought people would disregard his reports as mere fabrications, as he didn’t keep a diary for most of his journey and feels he would be prone to exaggeration.

So, from the get-go, we are confronted with the possibility that Pym’s story is the product of his imagination, that none of the events at sea took place.

For instance, if we assume that Pym dies after entering the chasm (the interpretation I put forth in my previous article), then it calls into question the entire novel, as we could not possibly know what happened to Pym. Indeed, if Pym died then it’s likely his diary was lost with him. Furthermore, since the entire crew of the Grampus and Jane Guy perished, there would be no-one to tell Pym’s story.

Now, just as Poe incorporates contradictions and ambiguities in his novel, ultimately making us question the truthfulness of Pym’s account, so does Magritte invite viewers to question what we are seeing (is the reflection of the man really a reflection?).

By associating this painting with Poe’s novel, Magritte may be highlighting the unreliability of narratives that suffuse the world of art.

Nothing can be taken for granted. Question your perception since what you see may not be entirely truthful.

In the end, the only idea that matters is this: mystery!

In a way, what Magritte is telling us with Not to Be Reproduced (and possibly with many other of his works) is that a painting is really just a painting.

In fact, a painting of a subject is always that subject as seen from the perspective of its creator.

And no matter how much you try to give meaning to it, you cannot be sure that the meaning you attribute to it is the actual truth.

Appearances can be deceiving, and the only way Magritte believes art makes sense is by feeling the mystery it evokes.

If you look at Not to Be Reproduced, I bet you can sense the mystery.

Expecting to see the face of the man, you are presented with a copy-paste of the man’s back, whereas the book is correctly reflected.

Explicitly, the reflection of the man in the mirror is just how Magritte saw his subject: from the back.

Implicitly, Magritte is pointing out that this is exactly the reason why you should not trust your perception of images, that you should not look for clues that could bring some sense within our reality. An artist paints with his mind’s eyes, and this is something intangible.

And isn’t unreliability what makes Poe’s novel a mystery of its own kind? Doesn’t Poe also invites us to doubt Pym’s account? Isn’t it obvious that there is no way we can confidently say what is reality and what is fiction? Shouldn’t we simply feel the mystery of what happened to Pym?

Surely, the similarities between Not to Be Reproduced and Poe’s novel could not have gone unnoticed by Magritte.

Not to Be Reproduced is surely an intriguing work of art.

I sometimes wonder what it would be like if the man in the painting moved, turned around, picked up the book on the mantelpiece, disappeared from the image. What would we see in the mirror?

Just the thought of it sends me a chill down the spine!

And there is another word for that feeling: mystery!

Magritte, spot on mate! 🙂

See you in the next article!

Masterpiece

cool

super cool thanks saved my work

Hi Pipinha,

I’m glad the article was useful to you!