This post is comprised of different sections

Take a look at our review of The Anthropomorphic Cabinet!

Learn more about Freud's theory of the psyche! Or check out the full explanation The Anthropomorphic Cabinet Explained!

This post is comprised of different sections

Take a look at our review of The Anthropomorphic Cabinet!

Learn more about Freud's theory of the psyche! Or check out the full explanation The Anthropomorphic Cabinet Explained!

Artist: Salvador Dalí

Year: 1936

Medium: Oil on wood

Location: Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf, Germany

Dimensions: 25.4 x 44.2 cm

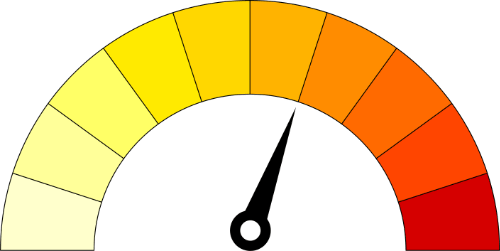

Our rating

Your rating

Ever since I was a teenager, I have always felt drawn to surrealistic paintings.

Surrealism is not about painting accurately. The emphasis is not on making life-like figures or objects with the aim to replicate what we observe in nature.

Quite the contrary.

Surrealistic art is less bound to rules on how and what you should paint. It encourages free association and juxtaposition of images as a means to express what goes on inside the (unconscious) mind.

Despite my passion for surrealisim, I must confess I feel awkward hanging surrealistic works in my flat. I dunno, everytime I looked at them I kind of feel daunted, as if the painting were engulfing me inside its weird realm (even paintings with non-intimidating elements but a wee bit of distorted reality already makes me unease).

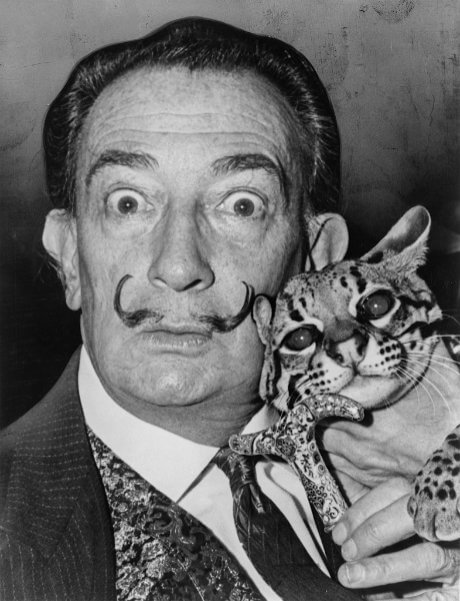

Now, if I asked you to come up with the first name of a surrealist that comes to mind, I bet that 99% of you would choose Salvador Dali.

Despite his eccentric (he had a pet ocelot that he took to restaurants) and often controversial (apparently he was a consummate scammer) character, Dali is deservedly one of the greatest surrealistic artists that the World has ever seen.

Similar to the effect David Lynch had on my thinking about movies, Dali had a profound influence on how I viewed the Arts in general.

I’ve seen my share of Dali’s original paintings in various museums, and, in all occasions, I was mesmerised. Call me a philistine, but I find Dali’s technique superb in comparison to most of his contemporary painters.

Not only was he able to paint big and detailed, but his works are smooth, graceful and brim with mindly – and downright bizarre – symbolism.

Dali was endowed with a phenomenal technical ability and a way of teasing us intellectually. It’s as though he were the conflation between a Renaiscence painter and a mischievous Psychologist.

Among Dali’s numerous paintings, the Anthropomorphic Cabinet is one of my favourites, and I’ll be analysing it in this article.

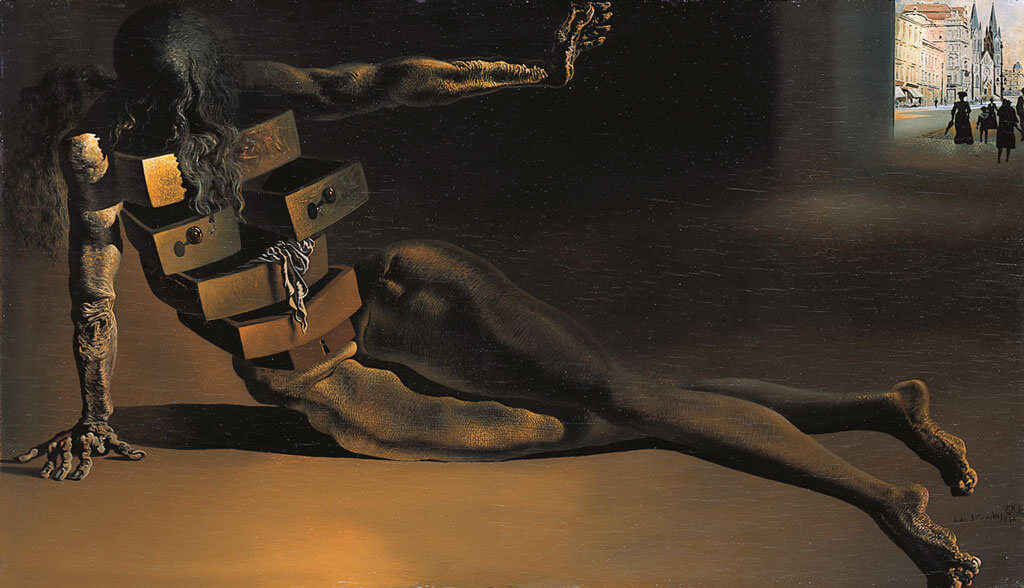

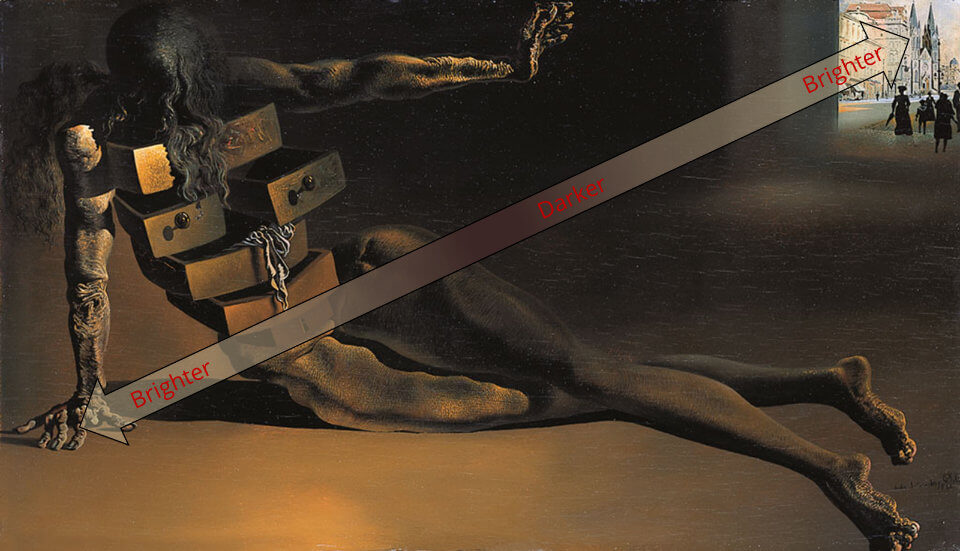

The Anthropomorphic Cabinet was painted in 1936 and shows a naked female figure reclining on one hand on the floor.

The most noticeable elements of this painting are the various drawers protruding from her torso. From one of those drawers a piece of clothing is hanging out.

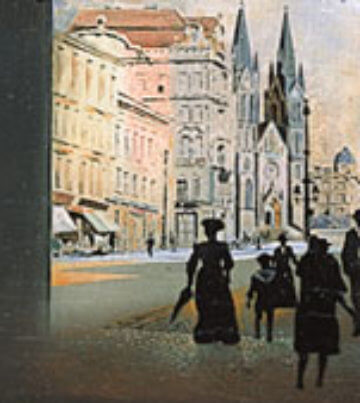

Her head is lying low and long hairs occlude any facial features. The body looks slightly disfigured and wrinkled, and the posture is one of despair. In the background we see what appears to be a typical street during daylight.

Visually, what captivates me most about this painting are the (almost) monochromatic colour scheme that Dali employed. The effect is not boring or repetitive at all, but rather dynamic, partly because of the manner Dali employed shadows.

But, of course, what really gets me going about this painting is it’s latent message.

Dali was influenced tremendously by the theories of Sigmund Freud, and this influence permeates several of Dali’s works.

As I will explore in detail below, the Anthropomorphic Cabinet is as much an artistic masterpiece as it is a visual description of the unconscious mind as envisioned by Freud.

The combination of skillful strokes coupled with a deep psychological meaning is the reason I am giving the Anthropomorphic Cabinet a well-deserved 4.5 stars.

Most of Dali’s works are surrealistic, so our Bizarrometer is bound to hover the top of the scale with any of them. Interestingly, most of the canvas is empty space really, which shows that you don’t need myriad of aberrant colours and juxtaposed elements for a painting to look bizarre. This particular painting gets a score of 4.

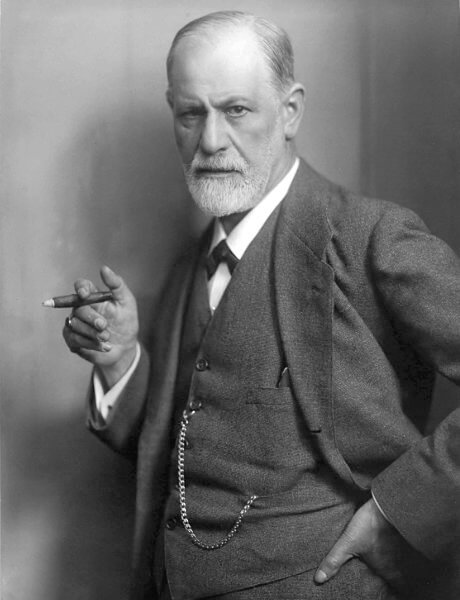

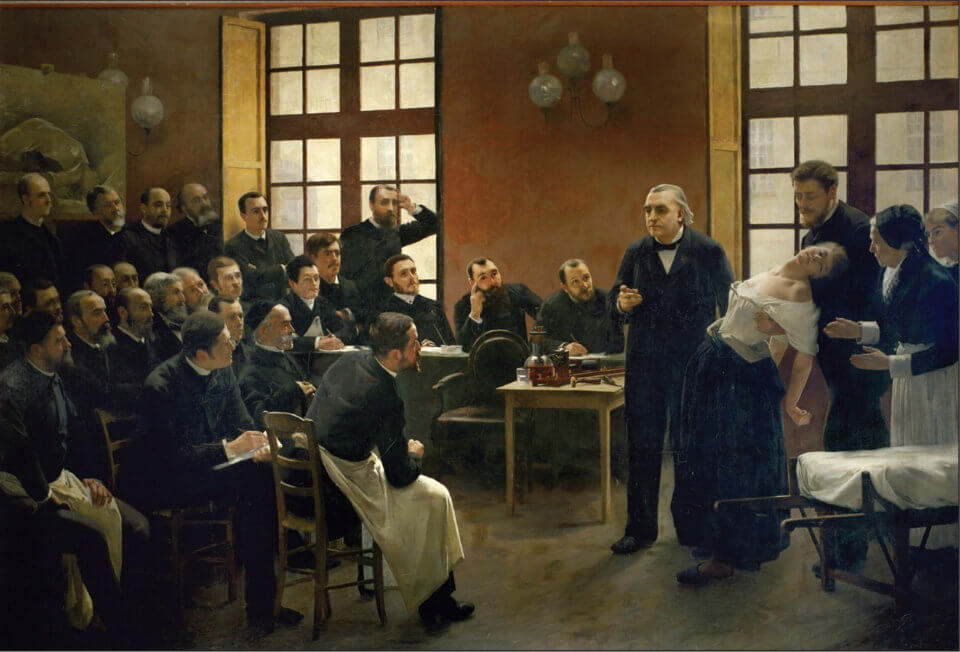

Undoubtedly, one of Dali’s major source of inspiration for several of his works was Psychoanalysis, a discipline founded in the late 19th century by Austrian neurologist Sigmund Freud.

Psychoanalysis was initially developed primarily as a therapeutic method for treating mental afflictions such as the infamous hysteria.

The goal of Psychoanalysis was to bring to light conflicts present in the patients’ minds that, so Freud believed, were the source of their psychopatologies. These internal conflicts were always somehow connected to unconscious wishes or repressions that had mostly taken place during the patient’s childhood.

As a young student, Dali was an avid reader of Freud’s writings, and yearned to meet the then-widely popular psychoanalyst on numerous occasions.

That event finally came to fruition on the 19th of July 1938, at Freud’s house in London. Even though Dali was 48 years Freud’s junior (Freud was 82 years old), they were both eminent personalities in their respective fields.

Of Freud’s theories, Dali wrote: “[they are] a kind of allegory which serves to illustrate a certain insight, to follow the numerous narcissistic smells which ascend from each of our drawers”. By drawers, Dali was referring to the reservoir of ideas, thoughts, wishes and memories which were unknown to the person – the unconscious mind.

The painting “The Anthropomorphic Cabinet” was painted two years before that memorable 1938 meeting, but it already shows how Freud’s ideas had a huge impact on Dali’s work.

The most distinctive feature of the painting, the drawers, was portrayed in numerous other paintings and scultpures by Dali, and he made sure the public knew what they represented: the drawers of our unconscious.

In this article, I will thus concentrate on the unconscious mind as seen by Freud, as this is, by most art expert accounts, the main theme of the painting “The Anthropomorphic Cabinet”.

Way back in ancient Greece, Greek philosophers saw Man as a “rational animal” above anything else. Humans, they believed, did not base their actions on basic instincts like “lower” animals. On the contrary, humans could steer their own actions at will to whatever aim they felt more convenient, and were never under the dominion of our most archaic impulses.

Even though some philosophers did acknowledge that humans possessed obscure wishes that could, at times, cloud our judgements, they more or less agreed that humans could combat these less noble desires with reason.

And so was the thought for the next 2500 years or so, until Mr Freud came into the picture and dropped a bombshell.

Freud studied and practiced medicine in Vienna, where, as I mentioned earlier, he founded Psychoanalysis. By examining both patients with a multitude of psychopathologies, as well as performing auto-analysis on himself, Freud concluded that humans’ seemingly rational behaviour was governed by an unconscious force – the libido, or sexual drive.

Uh-oh! If you do not immediately see the implications of this idea, Freud was essentially arguing that there was no real free-will. We were basically slaves of our most primitive, basic instincts that molded our decisions and actions, without us ever being aware of this influence!

As you might imagine, the puritanical society of late 19th Century/beginning 20th Century Vienna pretty much deprecated much of Freud’s ideas. Freud gained a considerable amount of opposition from the scientific community, and it was not long before his theories became a topic of ridicule.

Nevertheless, Freud’s determination did not falter and after some turbulent times he went on to become one of the most important figures of the 20th century.

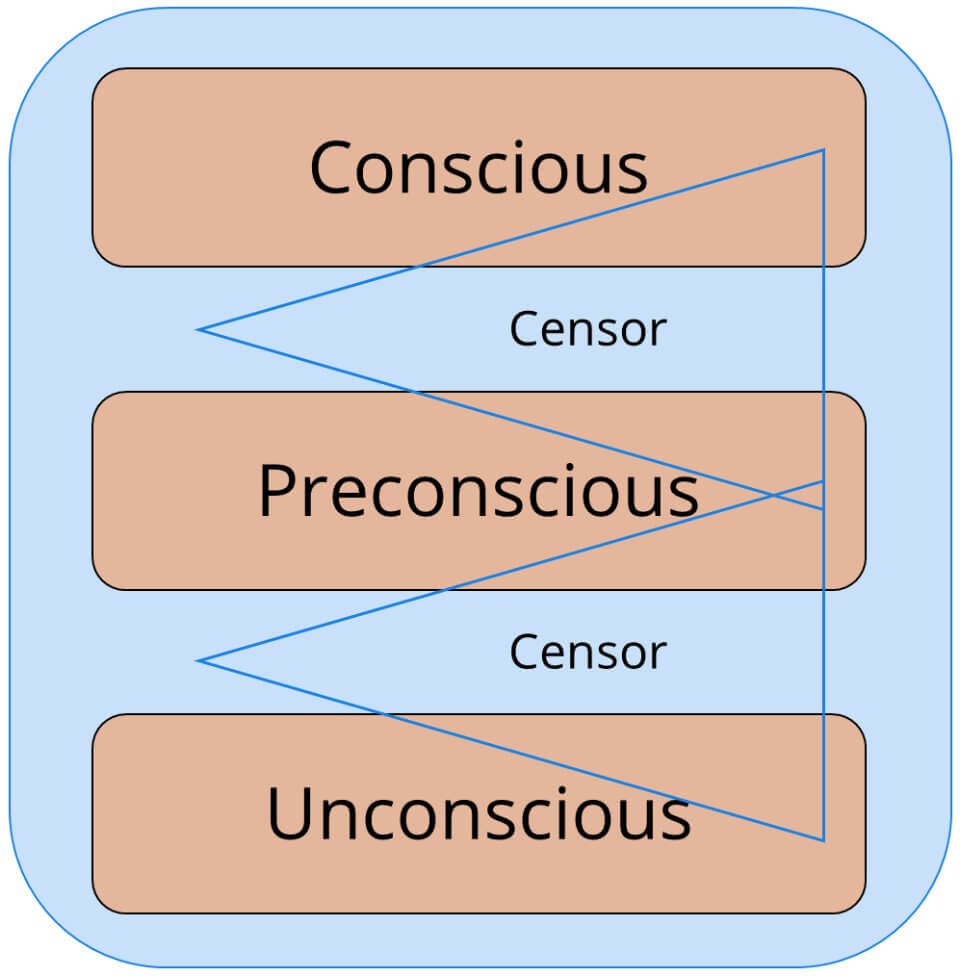

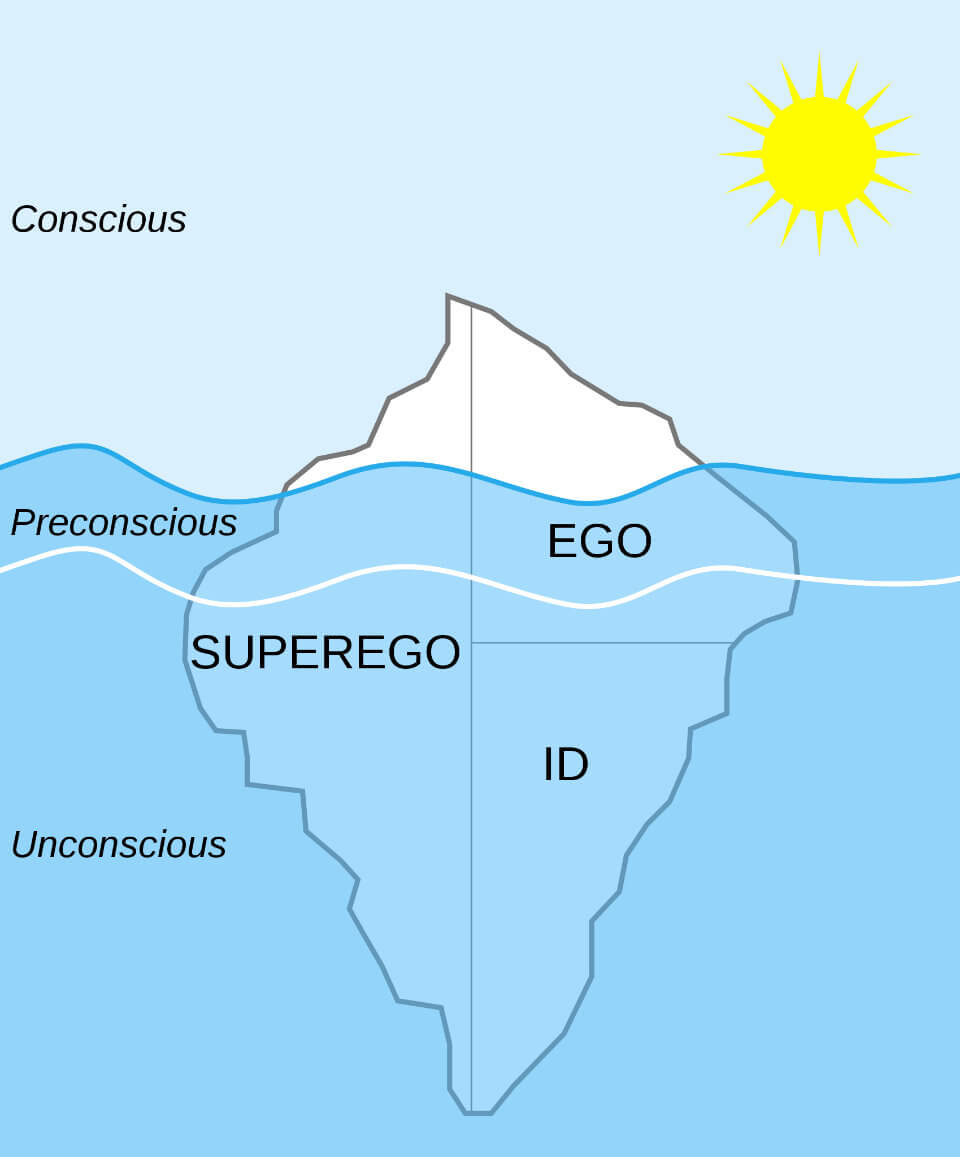

In his earlier work, Freud asserted that the human mind was compartementalised into a conscious, a preconscious and an unconscious “compartment”. These compartments, he went on, didn’t reside in physical brain regions, but were rather thought of as a representation of humans’ mental activity.

The Conscious mind was the place where your conscious thoughts were located. When you think I’m hungry; I am tired; I am a great supine protoplasmic invertebrate jelly – this is your conscious mind at work. Consciousness was therefore the part of your mind through which you interacted with others and the world at large.

The Unconscious mind, on the other hand, was where problematic and repressed thoughts or memories resided. For example, certain traumatic and painful memories (e.g., war atrocities, sexual abuse), or wishes that caused extreme embarrassment were all locked up in the Unconscious.

The Preconscious was kind of a middle ground. Things here could go either way – they could become conscious or unconscious, depending on the current situation and their emotional significance. For example, a recent event (e.g., hearing Dogtanian’s intro song) might trigger the memory of a mild emotional experience that had occurred in your youth (e.g., remembering once having spilled soda over your shorts while watching Dogtanian). So, that memory, which had been previously stored in the Preconscious, surfaced to the conscious mind.

How did the mind decide whether a memory should be promoted to Consciousness or demoted to the Unconscious?

For that task, Freud argued that there was a censor that served as a kind of psychic gatekeeper, deciding what contents to release to the other regions of the psyche.

In fact, Freud speculated that there were two instances of this censor: one situated between the Unconscious and the Preconscious, and another located between the Preconscious and the Conscious.

There was a good reason for the existence of this censor. Freud believed that once suppressed material loomed in the unconscious, it could not be accessed directly, as the censor would prevent most unconscious material to become conscious. It did this in order to prevent traumatic and painful content to have a negative effect on the person. However, if the memory was only slightly emotional, and perhaps even helpful, the censor would relax its grip on the memory and allow it to reach consciousness.

As Freud matured his theories, he became adamant that psychopathologies were the result of some internal conflict that had occurred sometime in the patient’s past. Due to their disconcerting content, the mind chose to bury it in the Unconscious, and stationed a vigilant censor to bar passage of this material to other parts of the psyche.

However, he viewed traumatic/embarassing memories and wishes as persistent, with the sole aim to ascend to consciousness. In order to escape censor’s constant surveillance, these repressed memories/wishes would appear camouflaged as symptoms.

That was the reason, according to Freud, why patients with numerours psychopathologies tended to exhibit such strange behaviour (e.g., emotional lability) – these symptoms were repressed memories, thoughts and/or ideas that surfaced under disguise.

It may not be obvious at first, but digging enough into the patient’s past and via a series of (at times, convoluted) associations, a talented Psychoanalyst would eventually be able to uncover the root of the conflict.

The stratification of the psyche into a Conscious, Preconscious, Unconscious and censor was developed as part of Freud’s first topic (topic comes from the Greek word topos, which means location. With it, Freud possibly intended to depict a map of the different locations that inhabit our psyche).

However, the first topic is by no means definite. Freud reviewed and expanded his theories over time and his second topic (which you might know from the famous image of an iceberg representing the Ego, Id and Superego structures – see above) is seen, by most academics, Freud’s more important theoretical model regarding the study of the psyche.

The first topic will be enough to interpret “The Anthropomorphic Cabinet” (no worries, there will be plenty of opportunities to discuss the second topic in detail in later articles). Nevertheless, there is one aspect of the second topic which I would like to mention here as it is relevant for the discussion of the “The Anthropomorphic Cabinet”.

During the subsquent years after the formulation of the first topic, Freud concluded that the human nature obeyed primarily to sexual instincts stored in the Unconscious.

You read it right! Freud was claiming that most decisions people took in their daily lives were, in one way or another, influenced by sexual instincts that had been somehow repressed in the Unconscious.

This sexual energy was the reason for many symptoms seen in neurotic patients, as I described above, although it could also be channeled to more productive activities, such as a friendly relationship, an aritistic work, a job, etc.

Now, this is going to sound weird…

Not only was Freud claiming that our conscious behaviour was mostly influenced by these unconscious wishes of sexual nature, but that these wishes could be traced back to experiences in early childhood (you may have heard of the Oedipus complex, which is arguably the quintenssential of these experiences).

Enough said about this though, because the psychosexual development in early childhood is a whole other topic that requires a dedicated article.

Let’s first begin with a dissection of the title of the painting.

Anthropomorphic means treating particular objects as if they had human characteristics. For example, Babar the Elephant is an anthropomorphism, because Babar has human traits (he talks, dances, and drinks tea with his fellow elephants).

A cabinet is a type of furniture with drawers and/or shelves.

So the name of the painting implies a cabinet with human qualities. Let’s rephrase this to really make a point here: the “woman” portrayed in the painting is not really a woman with drawers on her torso; it’s a cabinet to which Dali added female features.

We have just started out our journey and already made quite a progress in our analysis of this artwork: the primary element of the painting is an object, not a person.

The cabinet-woman could thus be seen as a representation of the unconscious mind, a cabinet that stashes all our primitive urges and desires.

Dali once said:

“The only difference between immortal Greece and contemporary times is Sigmund Freud, who discovered that the human body, purely platonic in the Greek epoch, is nowadays full of secret drawers that only psychoanalysis is capable to open.”

If you read the section on Freud and the unconscious mind, you should be able to understand what Dali meant with this.

The drawers represent niches of unconscious and repressed material that can only be revealed by proper psychoanalysis.

But why did Dali use drawers to symbolise the unconscious mind?

Well, if you think about the functionality of the drawer, it becomes clear that just as you can take clothes out, you can also put them in.

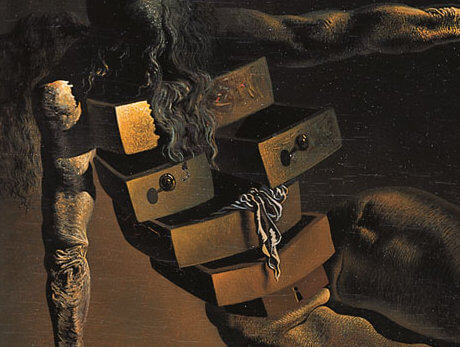

The drawer knobs are clear allusions to the nipples, whereas the key hole (you guessed it) represents the vagina.

With these two details, Dali is expressing one of the central theses in Freud’s psychoanalytical theory os the psyche: the human nature predominantly obeys to unconscious sexual impulses.

Take the piece of clothing sticking out from one of the drawers, which appears to be some kind of woman’s lingerie. Well, lingerie is a very personal feminine kind of garment, isn’t it? You do not walk around in underwear for a reason, and only people with whom you have intimacy get to see it.

In fact, the disposition of the clothes in the drawers could take three meanings:

1) if the drawers are opened with clothes sticking out, it could represent the attempt at bringing a person’s own repressed thoughts/memories/wishes to the surface.

2) if the clothes are kept inside closed drawers, it could indicate buried thoughts/memories/wishes in the depths of the unconscious.

3) if the open drawers contain no clothes, it could indicate successful integration of those memories into the self.

In this particular painting, the drawers are opened, most of them empty but the drawer with the lingerie. This could indicate attempts at making unconscious content conscious.

Another interesting composition aspect of the “The Anthropomorphic Cabinet” is the lighting. Your gaze is immediately directed to one of the brightest areas of the painting: the cabinet-woman. A bright light falls on the reclining and slightly disfigured female body, which appears to be in the process of disintegration. So, the light shining over the body could symbolise the shining over repressed material in order to bring it to light, to consciousness.

However, as with most unconscious repressed material, this experience might be a painful and shameful one. The despair look in the woman’s figure suggests shame, guilt and/or embarassment of some kind, and, as discussed above, the lingerie has a likely sexual connotation. This is related to Freud’s idea that most unconscious material are sexual (unconscious) wishes that are simply too disturbing to the mind. Note the head hanging occluding the face, as if to hide the shame and the strecthed arm as if begging for the observers (top right) to leave her be.

Indeed, facing repressed material can be very difficult, but it is necessary, since unresolved repressions often appear as unwelcoming symptoms. It is the job of the psychoanalyst to help the patient cope with these internal conflicts and guide him/her on the journey to resolve those conflicts.

At the top right corner of the painting, we can spot the sillouette of several human figures standing at the boundary between the inside and the outside world – the Preconscious.

The sillouetes stand out, which is perhaps an indication that they are significant elements in the narrative. But what might they represent?

As mentioned above, the final repressed memory (represented symbolically by the hanging lingerie) is crying out to be made conscious.

We could speculate that the individual holding this repressed memory needs to come to terms with these figures – perhaps acquaintaces or people that were integral to the formation of this repression.

Once the repressed event has been successfully integrated, these sillouetes will finally step out into the light (into consciousness; which is the brightest area of the painting), as the internal conflicts have been resolved.

Alternatively, the sillouetes could represent the internal censorship. According to Freud’s first topic, there are two censors: one between the Unconscious and Preconscious, and another between the Preconscious and Conscious.

The censor ultimately decides which material should reach consciousness and which material should remain buried in the Unconscious.

So perhaps these figures, who appear to be patiently observing whatever is going on inside the room, are simply judges of memories to come. If so, what outcome for the last repression do you think Dalí had in mind?

Freud’s tripartite theory of the human psyche (Consious, Preconscious, Unconscious) was a turning point in the history of Psychology, and the division between conscious and unconscious systems was one of Freud’s greatest contributions.

The Anthropomorphic Cabinet beautifully illustrates this divide, and Dalí did it with mastery. I find it interesting that Dalí chose not to overwhelm the viewer with colour and juxtaposition of objects as some other surrealistic art (even some of Dali’s other works).

Still, I cannot help but feel the despair in the narrative of the painting, as if something mysterious and disquieting was trying to reach out… Is there a better visual description of Freud’s idea of the Unconscious than that?

This painting reveals not only how technically gifted Dali was, but also his acumen in turning Freud’s abstract and complex psychoanalitical ideas into actual shape with a handful of compositional elements.

Freud must have been impressed!

Despite your feelings towards Freudian psychoanalysis there is little doubt that Freud was pioneer in bringing the unconscious to the fore, at a time when it was largely ignored (although to be fair, some philosophers, such as Nietzsche, had already proposed the existence of an unconscious mind). Today, science has confirmed the existence of an unconscious mind, as evidenced, for example, in various forms of implicit cognition.

Dalí, an avid reader of Freud’s works, likely saw the potential of Freud’s grand idea as a novel avenue for surrealism, and was quick to incorporate it in his own compositions.

At times, I daydream about that 1938 encounter between Freud and Dalí. Really, how awesome it would have been to witness two of the most illustrious personalities of that time exchanging thoughts and ideas about the unconscious mind.

See you in the next article!

Books

Martí, Marc Pepiol. Freud – Un viaje a las profundidades del yo. Shackleton books.

Néret, Gilles. Dalí. Taschen.

Leave a comment

Add Your Recommendations

Popular Tags