This post is comprised of different sections

Take a look at our review of Paprika!

Learn more about the sleep stages and their role in dreaming, the meaning of dreams and lucid dreaming! Or check out the full explanation Paprika Explained!

This post is comprised of different sections

Take a look at our review of Paprika!

Learn more about the sleep stages and their role in dreaming, the meaning of dreams and lucid dreaming! Or check out the full explanation Paprika Explained!

Author: Yasutaka Tsutsui

Publisher: Chūōkōron-Shinsha

Year: 1993

Language: Japanese

Country: Japan

Publisher (translation): Vintage Books

Language (translation): English

Number of pages: 342

Our rating

Your rating

I suspect that very soon a substantial portion of the content in Mindlybiz will have its origin in Japan. Why’s that, you may ask?

Well, I have watched countless Anime and read numerous Manga and Japanese novels that had some of the weirdest narratives I have ever encountered (and, unrealistic ambition aside, I plan to review them all!).

And it’s not like these kinds of Japanese fiction are simply weird without regard to a compelling narrative. Quite the contrary! I have found most of these works to be an ingenious mix of surrealism and deeply thought-provoking and original ideas.

It’s as though Japanese writers have a knack for creating psychological thrillers. Granted, not every work fits my liking: why the heck is this guy walking around with a paper bag on his head? But hey, to each his own, right?

Since my teenage years I have had a genuine interest in fictional works connected to the mysterious realm of dreams. The anime movie Paprika was recommended to me after watching the (also excellent) movie Inception.

However, being one of those people that always starts with the source, I decided to read the book which the film was based on. So, in this article I’ll be analysing Paprika, the novel by Yasutaka Tsutsui.

The novel introduces us to the main character Atsuko Chiba, a beautiful researcher and psychotehrapist working at the Institute for Psychiatric Research in Tokyo, Japan.

Her genius colleague and boyfriend Tokita has developed a portable psychotherapy device (the DC Mini) that allows therapists to infiltrate the dreams of patients, and, in the process, help them recover from their psychic ailments.

This technology is still being developed and lacks legislation. Because it is illegal to use, Atsuko treats her high-profile patients in her apartment, where some of the equipment is located. When meeting her patients, she puts on a few false freckles and a wig and calls herself “Paprika”.

Things soon start to go awry, however, after a series of the powerful dream-controller devices is stolen. She becomes aware that the technology is being used for nefarious purposes by two of her colleagues, who infiltrate the dreams of unsuspecting victims, wrecking their personalities.

Dreams and reality begin to merge with one another as a consequence of repeated use of the perilous technology, and Atsuko and her allies engage in a surreal endeavour to prevent the real world from falling apart.

Even though I had high expectations for this story, I must admit Paprika felt disappointing.

First of all, I find most characters over the top, and I can’t figure out if that was intended or not. For example, as Paprika, Atsuko invites her patients to come to her apartment where she scans their dreams. When they approach the door to her apartment, there is a metal nameplate fixed on the wall with the text Apt. 1604 CHIBA written in bold capitals.

Seriously?!?

So, Atsuko, who is allegedly one of the smartest scientists in the world (after all, she is nominated for the Nobel prize in Physiology or Medicine), runs an illegal research project in her apartment, which, by the way, is in the same building as her archenemy’s flat?

Even after she is under serious suspicion that she might be Paprika, she continues to bring patients into her flat. This is nothing but folly. Nowhere does Paprika attempt to explain why she is doing therapy in Atsuko’s flat; she appears to simply hope nobody will figure it out. Then later in the book she appears surprised when two of her patients realise that Paprika and Atsuko are one and the same person. Well, duh!

Atsuko’s method is also blatantly unethical. Although she claims that engaging in sex or flirting with her patients is a shortcut to their cure (!), she appears to do it for fun. For example, after treating Noda, she asks him to kiss her as she later tells her boss Shima, “[Paprika] didn’t go as far she did with you. But she did let him kiss her at the end. […] In reality, she found him rather attractive.” Did I forget to mention Noda is married with children, and Atsuko knows this?

Similarly, when she is about to have sex with Konokawa (another patient), she says “Never mind – this was just a dream. It would simply be one more secret to be shared between therapist and patient […]“. And then later adds that “She felt that this virtual sex act might be more immoral than a real sex act between a therapist and a patient who really loved each other […] Nevertheless, Paprika could continue her treatment based on erotic experiences without feeling too guilty about it. […] If Konokawa felt guilty about this method, she thought, she could always have sex with him properly after he was cured“.

Look, I wouldn’t consider these points flaws in the story if the character Atsuko had been portrayed as a rebellious psychotherapist with little scruples and integrity. But it was my impression that Atsuko was being depicted as a heroine, a virtuous scientist and respectable therapist, whose only concern is the well-fare of her patients. But, really, any actual psychotherapist would immediately demand her suspension at the knowledge of her work methods, let alone be nominated for a Nobel Prize.

Another implausible character is Atsuko’s boyfriend Tokita. Here we have a genius scientist that has been developing really sophisticated devices, but who, for a strange reason, is incapable of memorising a simple instruction: add protective code to prevent unauthorised access to the devices. Dude, a simple 6-digit pin code would do the trick!

Maybe I would understand if the memory lapse had occurred with the initial prototype. But after making 6 of them?! And he just leaves them lying around with no safe-proof mechanism? Also, one DC Mini had been missing for a long time (one that Atsuko had forgotten in her pocket!), and he didn’t remember to tell Atsuko that it was missing. No, it was necessary that all of them get stolen for him to bring it up. This just strikes me as completely absurd.

To be fair, Atsuko is well aware of this when she says that Tokita “was completely incapable of such meticulous afterthought”. That might have been an understatement!

Some sections of the book were also very uncomfortable to read. For example, Atsuko professes her love for Tokita but is apparently disgusted by his appearance, and has no compunction fooling around with her patients. She makes non-professional comments such as “Interesting people have interesting dreams. Dull people only have dull ones.”. Homossexuality is seen as something perverse: for example, the only two homosexual characters are coincidentally the villains of the story; Konakawa, a high-ranking police officer, comments about the homossexual relationship that “that’s disgusting”; when a female colleague makes flattering remarks about Atsuko’s appearance, Atsuko notes “feeling slightly embarrassed at such unfettered adoration by a member of her own sex“.

And I don’t even know where to start with the rape scene. Atsuko is violently attacked in her flat by one of her colleagues, but, in the end, he is unable to carry out the rape. However, Atsuko gets really annoyed with him, not because he tried to rape her, but because he didn’t actually consummate it! The attempted rape apparently got her horny and wanting to have sex! What?!?

Finally, I felt the organisation of the book left a lot to be desired. The first part of the book is almost detached from the second part, in which the most interesting events occur. Sure, the first part introduces the characters and sets the stage for the events in the second part. However, most of the dreams that Paprika analyses in the first part are completely tangential to the main plot and bear little importance to the novel as a whole.

One a more positive note, the written language was quite accessible (at least based on the English translation). Narratives involving dreams tend to get confusing very quickly and the jumbled up nature of the dream content has the potential to turn stories into a mishmash. I feared this in Paprika, but was happy to have been proven wrong. Certainly, I expected the dreams sequences to be very weird, but the descriptions of the dream imagery and the pace at which the dream narrative evolves is very adequate in my opinion.

I also enjoyed reading Paprika’s dream interpretations of the unquestionably complex dream narratives of her patients. You can tell the author did some research, and although I found Paprika’s psychotherapy unlikely (e.g., the dream theories of Freud and Jung are antithetical, but Paprika appears to endorse both of them), her interpretations were fun to read.

The concept of Paprika is a clever one. I do see the potential of the story and definitely congratulate the author for his fascinating imagination.

However, as outlined above, I found the book had serious flaws (e.g., incoherent characters, poor book organisation) which diminished my enthusiasm for the book. Here at Mindlybiz, Paprika gets a rating of 2 stars.

This is a tough one. The novel is divided into two parts. The first part is very accessible – there is a clear separation between the dream world and reality, which makes the story easy to follow. In part, that is due to Atsuko’s interesting therapy dynamics, interpreting dreams with her patients.

The second part of the book, however, begins to entangle dream and reality, producing a more confusing storyline. Nevertheless, the reader is never left completely lost and the author was careful to explain most dream-reality transitions as the novel progressed. Paprika gets a Bizarometer score of 3.

In its core, Paprika isn’t a particularly difficult story to analyse. All the ingredients for a good-guy-bad-guy sort of narrative are present.

On the one side, we have the heroine of the story, Atsuko/Paprika, with her unmatched beauty and wits; the representation of virtue, bravery and progressive views.

On the other side, we have Inui, a cantankerous old man, pestered by envy of Atsuko’s success. His sole intent is to discredit her and restore the conservative values of psychotherapy. He represents conformism and hidebound thinking.

Supposedly, one could interpret this divergence as a religious battle. The book makes it clear that Inui is a fervent Christian. A passage in the book, for example, reads that “[…] whenever he [Inui] treated Osanai with tender affection, he himself had come to resemble Jesus. He had even started to see himself as the savior of the psychiatric world“. When Paprika is about to depart to Sweden, Inui announces “The host of Christ, assembled on the plain of Jerusalem, declares war on the host of Lucifer on the plain of babylon“. Inui even chose a cathedral with the figure of Christ as the place for the last confrontation.

In contrast, during the Nobel Prize ceremony, a griffin begins to attack Paprika and Tokita, but Vairocana (the incarnation of Buddha) and Acala (the protector of Buddhism) materialise to save them – the two Buddhist images were none other than Kuga and Jinnai, respectively, the two bartenders of Radio Club and Paprika’s allies. Interestingly, there are several mentions of Kuga resembling Buddha, and it is Kuga who, unexpectedly, pretty much saves the day (see below). So, does this mean a victory of Buddhism over Christianity?

The first part of the novel introduces the reader to all relevant characters, as well as to the robbery of the newly developed DC Mini technology that plunges Paprika and her friends into a fierce battle for dream control.

Paprika and allies realise that the more the DC Mini is used, the more it pushes its users into a deeper and deeper sleep. Reality and dreamworld begin to conflate, putting sleepers at a serious risk of never waking up.

Mind-reading, teleportation of dream characters and objects into reality, and even time-travel are all side-effects that spontaneously emerge due to repeated use of the DC Mini.

Ultimately, it all boils down to who has the upper hand in controlling these side effects.

Although the battle between Paprika and Inui remains initially balanced, Inui’s power gradually increases as a result of his ever deeper sleep, and, consequently, giving him greater control over dreams.

By the end of the book, when nothing seems to put a stop to Inui’s dream turmoil, the battle unexpectedly ends, as Inui’s dream control wanes. Inui appeared to have been sleeping for days and days, eventually starving to death.

Because dream imagery disappears as soon as the dreamer wakes up (or dies), Kuga takes the opportunity to reset time and bring everyone to a not-so-distant past.

The book ends with a very cryptic chapter involving the two bartenders of Radio Club, leaving ambiguity regarding what was the dream and what was reality.

Before I expound on these points, I’ll describe some interesting facts about sleep and dreams.

When talking about dreams, it is inevitable to mention sleeping.

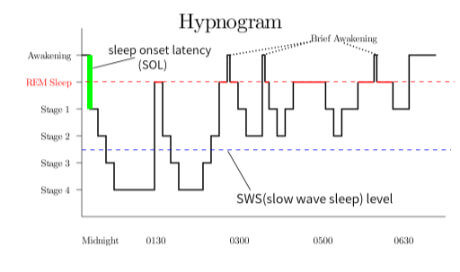

During the usual 7/8 hours sleep each night, humans cycle between two types of sleep every 90 minutes or so: REM (Rapid Eye Movement) and NREM (non Rapid Eye Movement) sleep.

NREM sleep is, in fact, divided into three distinct stages: N1, N2 and N3 (there is also an N4 but it is usually grouped with N3).

N1 is the lightest stage of sleep, so it’s very easy to wake up from. It is also the shortest, lasting only a few minutes as soon as you fall asleep, which can happen three or four times throughout the night. As such, N1 sleep is more of a transition stage between wake and sleep. The body has not yet fully relaxed, and brain activity only slows down slightly. One of its functions may be to tag current concerns or memories for later deeper sleep processing. N1 accounts for only about 5% of the entire sleep cycle.

During N2, heart rate and body temperature start to drop and muscles relax; breathing and brain activity also slow down. N2 sleep appears critical for the establishment of motor skill learning — automatic skills that do not require conscious awareness. Studies have shown that a healthy dose of N2 sleep helps people consolidate newly acquired motor sequences (e.g., finger tapping) that had been learnt the day before.

N3 follows N2 sleep and it is the deepest stage of sleep. It is colloquially referred to as slow-wave sleep, due to the larger (slower) brain waves. The “slowness” of N3 waves (called delta waves) are due to thousands and thousands of neurons all firing synchronously every two or three times per second. Muscle tone, heart rate and breathing rate continue to decrease as the body enters deep sleep; eye movements also come to a halt.

In general, N3 sleep is believed to be the phase when your brain is cherry-picking which memories to weed out and which are worth keeping. It also strengthens those important memories by transferring them from volatile storage sites in the brain into more permanent ones.

Additionally, it is during N3 sleep that important functions of neural sanitation mostly take place. When neurons do their work they produce dangerous by-products. It is during N3 sleep, that these contaminants are washed away by a fluid that bathes the entire brain (the cerebrospinal fluid).

N3 occurs mostly during the first half of the night, and can vanish completely in the second half, where it is gradually replaced by REM sleep.

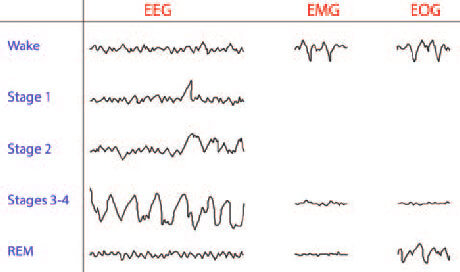

If you look at the electrical brain activity during REM sleep you will immediately recognise that it is almost indistinguishable from waking electrical brain activity. In fact, it is so similar that researchers need to monitor muscle tone to be able to differentiate the two (compare the EMG readouts between wake and REM in the figure above).

With NREM the deeper the sleep is, the more relaxed your body is. By the time you reach REM your ability to control your muscles is completely lost — you are effectively paralysed!

And that is not a bad thing.

Atonia, as this temporary paralysis is called, is caused by the brain sending signals to pretty much every portion of your spinal chord, instructing it to shut down momentarily. Exceptions to this rule are the muscles of the diaphragm, which control your breathing, as well as the muscles of the eyes, which dart around inside the closed eyelids, and, incidentally, the reason why we refer to this type of sleep as Rapid Eye Movement (REM) sleep.

As a result of this general stand-by, the muscles of your legs and arms are disabled, which prevents you from inadvertently kicking and punching your partner in your sleep.

Although we cycle in and out of REM every 90 minutes, the duration of REM sleep increases with each cycle.

The benefits of REM sleep are plentiful. For example, it regulates emotions, facilitates accurate recognition and comprehension, fuels problem solving and creativity, plays a crucial role in language learning during childhood, and tunes the ability to discern subtle emotional facial expressions.

People tend to associate dreams with REM sleep, but it is not true that we only dream during this stage. In fact, we dream throughout the entire night.

Researchers estimate dreaming by waking participants up as soon as they enter a particular sleep stage.

It is believed that about 75% of N1, 70% of N2 and 50% of N3 awakenings result in a dreaming report. For REM awakenings that number goes up to 80%.

N1 dreams are very short in duration (people don’t spend much time in this stage anyway), less emotional and less bizarre than late-night dreams. They most often relate to thoughts you are having shortly before you slumber. Hypnagogic dreams (dreams that take place during the transition from wake to sleep) occur during this sleep stage, and it as been suggested that it is N1 dreams that assist in problem-solving and creativity.

N2 and N3 dreams are longer than N1 dreams, and likely reflect associations of ongoing concerns the dreamer had just before falling asleep, with recent memories of the day.

REM dreams are probably what most people think of as a dream. They are longer, more emotional, more bizarre and have a much more complex narrative than dreams in any other sleep stage. The dreamer usually only observes dream events although it might occasionally interact with other dream characters.

There are, however, individuals who will be able to tell if they are dreaming or not, and a rarer portion of them are even capable of conjuring up objects and people at leisure (see the lucid dreaming section below).

One theory proposes that REM dreaming acts as a natural psychotherapy. Individuals with anxiety or depression that REM-dreamed about their painful waking experiences had a significantly higher recovery rate than those patients who dreamed about unrelated experiences. This has led researchers to argue that one of the functions of REM dreaming is to regulate negative emotions.

Based on your own dreaming experiences, you might believe that dreams are always bizarre and incoherent. However, this is not the case.

In fact, research suggests that only about 10-20% of dream reports contain more than two forms of bizarreness, such as a scene transformation or an incongruity.

NREM dreams also tend to be considerably less bizarre than REM dreams, and about 1/4 of REM dreams contain no bizarreness at all.

Furthermore, truly weird REM dreams only seem to appear later at night, and are often more emotionally intense and longer in duration.

Thus, due to their more recent occurrence, being more distinct, more emotional and longer, REM late-night dreams become easier to encode into memory, increasing the likelihood that we will remember them when we wake up.

Also, it’s not as if “anything goes” in the dream world. Even the bizarreness of dreams appears to have certain “rules”. For example, items that suffer a transformation inside the dream usually keep its class (objects tend to transform into other objects, people into other people, vehicles into other vehicles, and so on). There is rarely a dream in which an object transformed into a person and vice versa.

Prior to the 18th century, dreams had a purely metaphysical or spiritual explanation. People believed that dreams originated from supernatural forces and, therefore, that they contained divine messages or presages of some future events.

However, when it comes to the meaning of dreams, most of us will probably think of the widely popular dream theory of Austrian psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud.

In short, Freud asserted that dreams had two functions:

1) to allow the expression of repressed (sexual) wishes that had been formulated during childhood

2) to protect sleepers from being disturbed

Freud believed that (mostly sexual) wishes that were too embarrassing or disturbing for us to deal with, were locked away in the unconscious. To prevent sleepers from waking up due to this disconcerting material, the psyche positioned a censor that prevented this offending material from reaching consciousness.

The problem is that if repressed wishes stay in the unconscious for long, they start to wreak havoc. If they succeeded in resurfacing to conscious awareness, the individual would begin to experience symptoms (the infamous hysteria was, according to Freud, the result of repressed wishes that managed to reach consciouness, disguised as symptoms).

So, during sleep, when the censor is far less effective, these repressed wishes would find a way to be expressed. But remember, these wishes are so disturbing that, if people were aware of them, they would be terribly shocked and ashamed.

So, to prevent wishes from being expressed in full during sleep and causing people to wake up, another censor (the dreamwork) distorted the repressed wishes to such an extent that they became unrecognisable.

And there you go, on the one side, unconscious wishes would still be fulfilled (if partly), releasing some of the sexual tension lurking in the unconscious. On the other hand, due to the dreamwork, sleepers could go on sleeping undisturbed, happily oblivious of their most shameful secrets.

Hats off to Freud for putting on such a creative theory!

Although being popular in the entertainment business, the Freudian theory of dreams has been harshly criticised by the scientific community.

First, it is unfalsifiable: we can neither prove nor disprove his theory, as there is no clear way in which researchers can make predictions to test the main tenets of this theory.

Second, experiments in which psychoanalysis interpreted the same dream have led to markedly different interpretations with no similarities whatsoever, calling into question the reliability of these interpretations.

Another theory that was quick to catch on was that of Swiss Psychoanalyst Carl Jung.

Although Freud and Jung were contemporaries and initially enjoyed a good relationship, they parted ways after a series of disagreements between the two.

Jung’s dream theory was covered in detail in our article about Mulholland Dr (be sure to check that), but I’ll explain the theory here in a few paragraphs.

As I mentioned above, Freud believed that dreams were the consequence of the dreamwork distorting the content of embarrassing and disturbing wishes surfacing into consciousness. Jung, however, considered Freud’s dream theory outdated and too narrow in scope.

Jung viewed dreams as a rather ingenious way our psyche found to keep us informed on our mental health. Thus, to Jung, dreams contained messages from the unconscious that indicated which aspects of our behaviour we should modify in order to restore balance in our psyche.

Jung proposed the existence of a personal unconscious as well as a collective unconscious.

The Personal Unconscious is similar to Freud’s definition of the Unconscious: it is the location of memories that have been conscious at some point, but have been now relegated to the unconscious. These include recent memories that can still be brought to mind (e.g., a forgotten name) and/or repressed content (e.g., childhood trauma, unconscious wishes).

The Collective Unconscious, on the other hand, is unique to Jung’s theory. This is the place where mental templates, inherited from our ancestors, resided. Jung termed these templates “archetypes” and he argued that every single one of us was born with them.

In dreams, archetypes take the form of figures representing some aspect of our personalities. For example, the archetype of the Great Mother symbolises our capacity for nurturing. The archetype of the Wise Old Man reflects our inner knowledge and intuition.

The idea was that an archetype would always appear in dreams whenever there was an imbalance in our psyche.

For example, if you have been working like crazy and rarely see your partner and children, the Great Mother archetype could appear in your dreams as your own mother comforting you. This might alert you that you need to be more affectionate towards your family.

Another example: let’s say I’m torn between a job offer in Barcelona and one in Madrid. We might dream we get lost in a mountain, but a hermit (a possible image of the Wise Old Man archetype) appears, pointing me in the direction of an enormous cathedral (symbolising the Sagrada Familia). Perhaps my unconscious decides that Barcelona would provide a most welcome revitalisation.

Note that these archetypes draw their energy from our personal and cultural experiences, so they show us what our unconscious mind believes is the correct decision.

As captivating as it might be, Jung’s theory of dreams suffers from many of the same problems as Freud’s theory, most importantly, the lack of clear hypotheses that could support or falsify it.

The idea that dreaming aids in creativity is nothing new. Many famous works of art have been inspired by the dreams of their makers. For example, the melting clocks of Dali’s famous painting “The Persistence of Memory” are believed to have emerged during his dreams.

There have also been proponents of the idea that just as dreams can help you create something awe-inspiring, they might also help you solve real-life problems and even have breakthroughs.

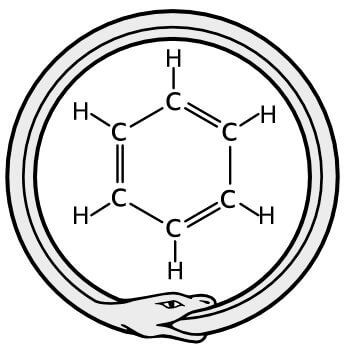

One of the most amusing examples of dreams as problem solvers is that of the discovery of the structure of benzene (C6H6) by German chemist August Kekulé.

Kekulé knew that benzene consisted of six carbon atoms each attached to a hydrogen atom, but how these six carbon and hydrogen atoms arranged to form the molecule had eluded him. None of the configurations he came up with made any sense because they violated the rules of chemical valence.

Then Kekulé had a revealing dream. He dreamt that the atoms were dancing before his eyes forming structures resembling snakes in motion. Suddenly, one of the snakes bit its own tail (like an Ouroboros, see figure above), playfully spinning before an incredulous Kekulé, at which point he woke up.

The Ouroboros gave Kekulé the idea to re-arrange the carbon atoms of benzene in a way such that each atom would be attached to two others, forming a hexagon ring (see figure above). The structure was completely bizarre in Chemistry at the time, but it was correct!

Even if Kekulé’s account has been greatly dramatised, controlled experimental studies have shown that dreaming about certain problems can be beneficial for their resolution. For example, subjects who had navigated a virtual maze prior to taking a nap, showed significant memory improvements later in the task if they had specifically dreamt about the elements of the maze.

Still, scientists suspect that most of these problem-solving dreams come from N1 sleep (which are a tiny portion of dreams we have throughout the night). In fact, dreams that actually solve any real problems are extremely rare. Such insights often only come after their dreamers had pondered about the problem for days, weeks or even months.

Below is a non-exaustive list of names of famous people whose inventions and artistic works were inspired by their dreams:

What if I told you a story of someone at a campsite who voluntarily decided to jump into a camp fire, started playing with the flames and actually ate them, noting a slightly salty taste, and all of that without getting a single burn? What if that wasn’t enough, and she flew in the direction of the sun, ever faster, ever closer, to the point she couldn’t see anything other than light, and feel anything other than a sense of vibration?

If you think only in your dreams someone could pull off something like that, you hit the jackpot!

The story I just described above was a lucid dream experience reported by dream researcher Beverly D’Urso during an interview with Psychology Today.

Lucid dreaming is defined as the awareness that one is dreaming while in a dream.

Some of you might have had those kinds of dreams where you doubt whether you’re indeed dreaming or not, which is a proto-version of a lucid dream (a so called “pre-lucid” dream).

But there are individuals who not only know they are dreaming but can actually recall, inside the dream, where they are sleeping and what day of the week it is.

If that wasn’t cool enough, some can even manipulate their actions in the dream, make objects appear or disappear and grow supernatural powers like flying. They also have logical reasoning inside the dream, which, coupled with the ability to conjure up memories from waking life, allows these individuals to try out things they always wish to do in dreams.

Note, however, that lucid dreaming doesn’t necessarily imply dream control. You can be aware that you’re dreaming but not be able to control anything at all (you are only an observer).

In fact, most lucid dreamers will only be able to influence the course of the dream. For example, they can make a person suddenly appear in the dream, but they will not be able to control what that person does or says. Likewise, you might be able to teleport yourself to a place of your choosing (e.g., a market in New Delhi), but the finer details of that setting (e.g., the spices being sold, the colours of the stands, etc.) will not have been consciously defined by you.

Nevertheless, about one third of lucid dreamers have the ability to summon objects or people into the dream, and, apparently, it all has to do with expectation. While dreaming, it is often recommended to imagine the object/person you wish to see, then slowly turning around and convince yourself that the desired object/person will appear.

Still, even though experienced lucid dreamers are capable to make people appear in their dreams out of thin air, they still have no clue how that person will react. It’s as though each dream character has a volition of its own, which, if you think about it, is really odd since all dream characters are the product of the dreamer’s imagination.

But the bigger question is: are the people who claim to lucid dream really doing it, or are they pulling our leg?

One way to verify the authenticity of lucid dreaming is to conduct an experiment, in which lucid dreamers indicate via ocular signals the exact moment they become lucid. In addition, they can also signal the moment when a particular dream action began and when it ended (e.g., running).

That way, researchers can track the physiological activity (e.g., heart rate) associated with the moment in time when dreamers began their lucid dream as well as when they performed a specific dream action.

Results have shown that when lucid dreamers signal that they are doing physical activity in the dream (such as running), researchers detect significant changes in the heart rate of the dreamer at the exact momement they indicate they are performing those actions. These physiological changes are similar to those when people exercise while awake!

But, and this is key, the simultaneous recording of their electrical brain and muscle tone activity is characteristic of a sleeping brain, proving that they are indeed asleep.

No doubt! These individuals not only are aware they are dreaming but can also communicate with the outside world! Truly astonishing!

Hopefully, you’re now slightly more familiar with certain facts and theories about sleeping and dreaming, so let’s dive into the novel Paprika.

I’ll begin my analysis of Paprika by expounding on critical themes in the novel, namely, the functionality of PT devices, Paprika’s methods of analysis, Inui’s and Osanai’s plan to take over the dreamworld, and the dream battle in the second part of the book. As a curiosity, I have also added a section on Jinnai and Kuga, the two enigmatic bartenders of Radio Club.

The information in the sections below is explained, in some way or another, in the novel. I decided, however, to wrap and condense all the relevant information within each of these sections for ease of understanding.

For you people that arrived here after only having watched the movie, some of this information will be new to you. However, you might still benefit from reading these sections as it will give you a bit more background about the story, which has been greatly curtailed for the movie.

Before Atsuko and Tokita introduced their innovative technology, psychotherapy was mostly conducted in the conventional therapist-patient conversational setting.

With the advent of a series of devices invented by Tokita (the PT technology; PT stands for PsychoTherapy), in collaboration with Atsuko in the past few years, conventional therapy has been gradually replaced by the usage of these PT devices for treating mental disorders. This is particularly true at least at the Institute for Psychiatry in Tokyo, where Atsuko and colleagues are working.

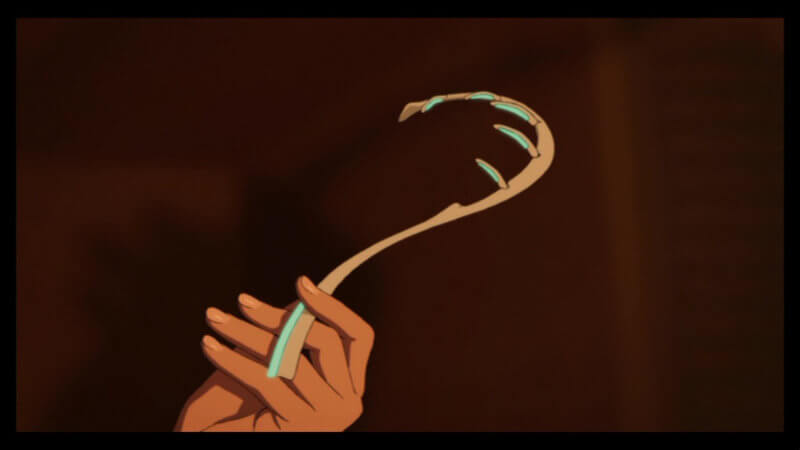

The standard procedure consists in the patient wearing a helmet called a “gorgon” — a highly sensitive sensor that detects brain waves. The therapist also wears a device called a “collector” with which she can enter the dreamworld and induce emotions in patients and observe how that influences their dreams.

The gorgon and collector are cabled devices, some of which Atsuko keeps in her apartment so that she can treat her patients behind closed doors.

There is also a reflector that can detect users intentions, and if the reflector detects that the collector is being used for nefarious proposes, it will deny access to entering the patient’s subconscious.

It is unclear if any of these devices induce lucid dreaming, although they must, since even patients without any previous training understand they are dreaming from the very first therapy session.

Even though lucid dreaming tends to occur during REM, it is more likely that Paprika and her patients remain in N1 sleep — the transition stage from wake to sleep when most hypnagogic dreams take place. This is the lighest form of sleep and when most problem-solving dreams occur.

Now, a new generation of PT devices is introduced somewhere in the middle of book. Tokita named them DC Mini, which stands for Daedelus Collector. Mini because, as opposed to gorgon, this one is smaller and wireless; you can basically just attach one of these things on the head (e.g., with scotch tape) and you are ready to go.

One major problem is that there are no access restrictions in place for the DC Mini, so anyone could in principle use it to enter the subconscious of any unsuspecting dreaming person.

Moreover, there are several side effects of using the DC Mini that do not exist with the older technology.

Some do not seem adverse. For example, anaphylaxis occurs when someone uses the DC Mini for long periods of time, increasing its effective range of influence. Whereas a collector has limited range (possibly only within the remit of Atsuko’s bedroom), the maximum distance the DC Mini is effective at is limitless. So with repeated use a DC Mini user can enter dreams remotely, even if another dreamer is located kilometers away from the DC Mini user.

In fact, after wearing the DC Mini for an extensive period of time, a user could access dreams even without DC Mini, by exploiting the residual effects alone. However, these effects are temporary, and the strength of control won’t be nearly as potent as it would be if one were actually wearing one.

Another (potentially useful) side-effect is that the DC Mini also allows its users to read another dreamer’s thoughts. This could be useful in cases where a therapist might wish to find out what someone is really thinking. For example, during a dream confrontation with Inui, Paprika asks him where he has stashed his DC mini to force him to think of the place where he hid it, as she will be able to access those thoughts.

Towards the end of the book, Paprika realises that the DC Mini has the effect that you can teleport objects from the dream into reality. The way it works is that whatever object a DC Mini user grabs in the dream is reduced to atoms and instantaneously resynthethised in the place where they are physically wearing a DC Mini. This function was not actually programmed into the DC Mini but it spontaneously developed as a side-effect of using one.

A definitely more gruesome side-effect of prolonged use of the DC Mini is that it starts to be absorbed by the human head, to the point that it will be impossible to remove it, even surgically, without first killing the user.

In addition, repeated use of the DC mini causes the wearer to fall into a deeper and deeper sleep while inside the dream. Although this might allow you to gain more control over the dream setting, it becomes increasingly difficult to wake someone up once you enter deep sleep (for example, if someone holds Paprika’s nose to interrupt breathing, Paprika would just dream she was suffocating, and this could kill her in reality).

Equiped with an arsenal of PT devices, Atsuko uses the technology to treat her high-profile patients.

As I mentioned above, it is clear that Paprika (and her patients) are lucid dreaming, because she is, in most situations, aware that she is dreaming. Furthermore, she is able to conjure all kinds of superpowers like flying or making objects appear out of nowhere (see also the sub-section Summoning dream objects into reality).

For the actual analysis of her patients’ dreams, Atsuko subscribes to several theories of dreams.

First and foremost, Paprika draws on some of the ideas put forth by Freud. For example, she states that one important method is the transferring of her own emotions via the collector into the patient’s subconscious. This has the effect of turning something neutral into something pleasant and desirable, mostly connected to early sexual wishes during childhood and early youth. That way, Paprika will be able to decipher the origin of her patients’ malady, because, according to Freud, unconscious wishes lead to a range of neurotic symptoms if they aren’t resolved with proper psychoanalysis.

Her method of recording images in the collector only when the conscious mind has relaxed its grip is also reminiscent of Freud’s postulation of a censor that blocks unconscious/repressed material, which can only come to light when the censor relaxes during dreams.

On the other hand, some of Atsuko’s dream analysis borrows ideas from Jung’s theory of dreams. For example, at the beginning of the book, she suggests that injection of emotions into patients’ subconscious could make them change the dream to a scene that made them realise that something needs to alter in their life. This relates to the Jungian idea of archetypes — innate “templates” inherited from our ancestors that are usually invoked in dreams and point to specific aspects of the dreamer’s life that require attention.

There are also sporadic suggestions that Atsuko believes that one of the functions of dreams is problem solving. For example, during an interpretation of one of Konokawa’s dream, Paprika mentions that dreams provide clues to solving criminal cases.

As I mentioned already, it would be somewhat peculiar that a psychotherapist of the caliber of Atsuko based her therapy on conflicting theories. Specifically, Freud’s and Jung’s dream theories are almost opposite in respect to the meaning of dreams.

In order to be able to observe her patients’ dreams, Atsuko has also developed the ability to sleep lightly and almost immediately when treating her patients. She refers to it as autohypnosis, and it could be that the stage of sleep Atsuko learnt to remain in is N1. During N1, you still have much of your muscle tension, and it is during this stage that dream-aided problem-solving is most likely to occur.

Why is light-sleep important? Because it allows Paprika to restore her waking awareness at will. If she falls into a deeper sleep, it will be harder for her to wake up voluntarily, and she will not be able to bring herself to waking reality. This might refer to stage 3 of NREM sleep, when it becomes more difficult to wake someone up.

The book mentions ways to wake up however: using drugs, self-waking devices, or sleeping on a chair in front of the (older) PT device (which makes it easy to abort the programme I suppose). However, if dreaming transitions to REM, it will be impossible to operate PT devices. This could relate to the fact that, during REM sleep, the body is effectively paralysed, as I explained above.

In dreams, DC Mini users can be woken up if they get scared by something unexpected (e.g., loud ringing of telephone next to you), if something arousing happens (e.g., erection and ejaculation) or due to dreason (dream reason; guilty feelings produced, for example, by having unlawful sex in the dream, shameful enough to wake the subject).

Indeed, this is one of the strategies Paprika employs when she realises she has fallen into a deeper sleep and is unable to wake up using her usual methods. She asks Noda to rape her in front of Konakawa in the dream, which causes discomfort for both of them and causes them to wake up.

Individuals that can lucid-dream do mention that keeping your emotions in check while lucid dreaming avoids waking up. Similarly, keeping mentally focused helps preventing falling back into a non-lucid dream state.

Because the DC Mini has the effect of deepening sleep, which might prevent you from coming to reality, Noda and Konakawa have the idea that their DC Minis should be removed as soon as they fall asleep to help Paprika. This proves to be another successful strategy, as they can still access dreams through residual effects of the DC Mini.

Contrary to the film, Inui and Osanai are depicted as the villains of the story from the start in the novel.

They both share the belief that the world of psychiatry has succumbed to the rapid advances of technology, shifting thinking away from conservative practices, to which they both vehemently defend.

In their opinion, where therapists used to treat patients using human psychotherapy, has now been replaced by blind trust on technological devices that have not yet been thoroughly tested.

Above all else, they despise Atsuko and Tokita, as they believe the PT devices they developed are amoral. Inui and Osanai belive Atsuko and other adherents of this technology are violating the mental space of their patients for the sake of technological advance and recognition. On top of that, Atsuko and Tokita are on their way to receive a Nobel prize, something Inui opposes fiercely.

Inui had previously been shortlisted for the Nobel Prize of Medicine for the discovery of a method of treating a psychosomatic disorder that had become widespread at the time. Alas, a certain British surgeon incorporated Inuis method into his theory and received the Nobel prize instead.

To Atsuko, this is the reason why Inui is so obsessive about ethics and justice and why he is so jealous of Atsuko, Tokita and their invention.

To thwart Atsuko and Tokita’s chance of winning the award, he instructs Osanai to project the dreams of schizophrenic patients into some of Atsukos collegue therapists, either subliminally (as with Tsumura and Shima) or explicitly (as with Himuro). All of them were fervent adherents of these PT devices and were either actively using them in psychotherapy, or involved in their conception.

Once the infected victims were locked in their subconscious forever, their personalities would be completely destroyed. Blame would subsequently fall on Atsuko, Tokita and Shima (the current president of the institute) for bringing those abominable devices to actual treatment. Inui would become president of the institution by unanimity and, as a consequence, would have full control over the functionality of the DC Mini and the decisions regarding its use.

This is essentially Inui’s aim: he sees himself as a kind of saviour of the psychiatric world, and has no compunction in hurting Atsuko and bring the others down if it means restoring human values to psychoterapy. A clear case of the end justifying the means.

Clearly, the most interesting event of the entire book is the “dream battle”, encompassing all confrontations between Inui/Osanai on the one hand and Atsuko and her allies on the other hand, which takes place in the second part of the novel.

It seems that the first part serves as an introduction to the characters and sets the stage for the dream battle that occurs in the second part of the novel. It also serves to make the reader familiar with the dreamworld, although Paprika’s dream analyses in the first part of the book bear little relevance to the main dream battle.

There are three decisive dreaming aspects that ultimately decide the fate of the battle: 1) the ability to control the dream (i.e., the capacity to define and/or change the course of the dream), 2) the ability of the DC Mini user to transport objects/people from the dream into reality, and 3) the ability to control time.

The battle between Inui/Osanai and Atsuko was really the question of who had the upper hand. Whoever managed to control dreams and their effect on reality, was free to dictate the setting and progression of the dream and invade other dreams at will.

One way to gain control of dreams is by “joining” dreams of several sleepers together, as this tends to overwhelm any single sleeper. This is clear with a passage in the book where it reads “Since the men were in the majority their dreams overwhelmed Atsuko’s. She had no idea where her dreams had gone“.

For the final battle, we have then Atsuko and her allies Tokita, Shima, Noda, Konakawa, Jinnai and Kuga on one side, and Inui and Osanai on the other side.

However, dream supremacy appears to belong, in most situations, to Inui. For example, during the Nobel prize ceremony, Atsuko realises that a dream that had started with Noda suddenly became Inui’s dream.

In addition, Inui is able to unleash all sorts of phantoms, monsters and japanese dolls from his dreams to the waking world, running havoc in the city, and Atsuko and friends can do little to counter-atack.

One might wonder how Inui gained so much power in the dream battle, if Atsuko and her allies clearly outnumbered them.

Paprika mentions at some point in the book, that she wouldn’t be able to attack Inui directly in his dream because his resistance would be too great. She would need to make it her own dream. However, in order to do so meant that she would need to enter a deeper sleep and, as I explained above, there are downsides to this (such as losing control over one’s actions).

In fact, this loss of control did happen to Atsuko once. During a dream encounter with Osanai, he transmitted Himuru’s nightmares into Atsuko’s dream. Atsuko had a hard time waking up, which she found strange, as she can usually wake up from autohypnosis easily by herself. Confused, but resigned, she went back to bed, woke up again and moved on with her habitual routine. As it turned out, Atsuko had entered deeper sleep and was still dreaming (false awakenings are, indeed, a feature of lucid dreaming).

This is a very dangerous side effect of the DC Mini. It makes you dream, then dream of waking up, and go back to sleep and dream again, in a never-ending loop. Because it feels like reality to you when you wake up, you get stuck in this loop of sleeping, dreaming and waking up in a dream, falling into an even deeper sleep, dream even deeper dreams, and so on.

I believe this was Inui’s fate. After the last battle, which ends with Inui’s defeat, it appears that Inui had used his DC Mini for so long that it became deeply ingrained into his skull. This suggests the effective range of Inui’s DC Mini was limitless and its effect probably stronger than the dream powers of Atsuko and friends combined, thus explaining Inui’s incontestable dream-control superiority.

Because of the known side-effect of wearing the DC Mini for prolonged periods of time, he fell into a deeper and deeper sleep, giving him more and more control over the dream. The drawback, of course, was that once Inui entered that petrifying sleep stage, dreams became reality to him. Remember, entering ever deeper sleep due to DC Mini overuse will get users stuck in a loop of sleeping and waking inside the dream, and they will end up believing it to be reality.

Therefore, even though he could control his dreams with ease and steer them in the direction he desired, he sealed his fate by never being able to wake up again. In the end, he died of starvation.

As I mentioned in the lucid dreaming section, some individuals have the incredible ability to create dream objects out of thin air. Some of the tips provided by lucid dream researchers and lucid dreamers alike is to imagine the objects you’d like to see in the dream and convince yourself that the object will appear when you turn around.

This is a tactic Paprika and her friends employ while dreaming. For example, the book mentions that “Paprika envisioned an elevator with its doors open […]. The elevator appeared on cue.”.

However, in the novel, invoking objects in dreams takes on a whole new level when the characters become aware of the possibility to invoke dream objects into reality. There are many of such occurrences in the novel, here are a few:

All of this suggests that objects, including people, that exist solely in dreams can actually be brought to reality.

Nevertheless, objects that materialise during dreaming must come from someone who is dreaming, so as soon as that someone wakes up these objects should disappear. However, this doesn’t seem to be the case for some of the examples I mention above, which suggests that even if the dreamer has woken up, his/her dream objects can temporarily remain in the waking world, probably due to the residual effects of the DC Mini.

In the “dream battle”, it isn’t only Atsuko’s and Inui’s dreams that begin to merge with reality. Even the dreams of people that were not wearing DC Minis (but came into contact with people wearing them) begin to merge with other dreams.

Towards the end of the battle, Atsuko realises it is possible to summon “dream powers” into reality – that is, invoking some dream character or object into the real world. This happens with Atsuko, when, in the real world, she managed to switch to Paprika.

Note that I’m not saying she disguised herself as Paprika. Nor am I saying that she was sleeping and summoned objects into reality. No. What I mean is that Atsuko was actually able to transform herself into dream-Paprika in the waking world! Shortly after, when meeting Osanai, she switches back again to Atsuko. Somehow she can summon the strength from her dreams while she is awake, although it appears to happen spontaneously (she does not know how to control it).

Finally, there is one side-effect of wearing the DC Mini that tops all others, and that is the ability to time travel.

Apparently, it is possible to use the DC Mini to travel backwards in time. Even though Tokita suspects Inui is able to do it, it is Kuga, the modest bartender of Radio Club, who is endowed with the power to actually bring it off!

Chronologically, the final dream battle takes place between the Nobel Prize ceremony and Inui’s defeat. However, it is as if it hasn’t actually happened because Kuga reset time to the point of Atsuko’s award announcement.

Now, it isn’t clear whether Atsuko and the others remember the events of this final battle. My suspicion is that they do, as in their final conversation in Radio Club, Shima asks Kuga if he has recovered. Shima is possibly referring to the fact that Kuga collapsed after managing to bring everyone to the past.

A lingering question is left though: shouldn’t Inui be alive?

After all, he was alive when he broke into the Nobel Prize ceremony, and Atsuko and the others traveled to this point in time. But Inui is dead, which means that the effects on him (i.e., his death) were also brought back to the past. It makes a certain sense, otherwise Kuga wouldn’t have felt the need to recover from the DC Mini side-effect of time traveling.

This suggests that time did go backwards but people’s memories remained unaltered (that is, they brought all the memories to the past with them). Unfortunately, the book ends with no further interaction with people other than Atsuko’s closer friends, so this remains highly speculative.

The two waiters working in Radio Club are, in my view, two of the most important characters of the whole novel but, at the same time, two of the most mysterious.

Why do I say that?

For starters, it’s very weird that Radio Club is always empty, and the only customers that frequent the bar are Paprika and her prospective patients.

When the final battle ensues, Jinnai and Kuga seem completely oblivious to what is happening outside, although the city is in a complete disarray. They do not appear worried after Paprika explains what is happening and immediately agree to help her fight Inui and his phantoms.

Strangely, Kuga appears to possess Atsuko’s ability to sleep immediately, even when a vulture barges into the bar and starts attacking everyone. Similarly, Jinnai is able to invoke objects at ease (he even wonders “if he had some alter ego, a secret past“).

Furthermore, Kuga appears to know that it is possible to travel back in time even though he could not possibly have known that since the only time this is mentioned is during a conversation between Tokita, Matsukane, Shima and Tokita’s mother.

Even if he had come across this information, how could he have developed the ability to control time the very first time he enters dreams? In fact, it seems that neither Atsuko nor Inui is capable of pulling out that feat, but Kuga, a simple bartender with no experience in using DC Minis can? Very strange! Either this is a terrible oversight from the author, or Kuga (and Jinnai) are more important characters than we give them credit for.

Clearly, the most cryptic event in the whole book (which happens to be completely omitted from the film), is the final chapter, in which only the two waiters are having a conversation and Jinnai asks the question “So – it was all a dream, was it?“.

What the hell?!? Is Jinnai insinuating that every single event in the book was a dream, or only the dream battle event? Remember, Jinnai and Kuga were indeed dreaming when fighting Inui, but they were affecting reality, so it was not all a dream. The whole conversation between the two is very vague and riddled with ambiguity.

One thing is clear to me though: Radio Club does not appear to exist independently of Paprika. We never see anyone in the bar when she is not around (at the beginning of the novel, Noda is sitting alone waiting for Paprika, but she appears shortly afterwards). Everytime, Radio Club appears Paprika is present. So what could this mean?

Here is one of the rare occasions where the film offers more to say about this than the book. In the film, Radio Club is a fictional place where Paprika meets her patients in their dreams. Interestingly, the author of the novel, Yasutaka Tsutsui, lent his voice to Kuga so I guess he hasn’t objected to Radio Club being depicted as belonging to the dream world.

So, an intriguing possibility could be that whenever the Radio Club emerges, that would indicate we are entering someone’s dream, probably Atsuko’s dream. Perhaps Jinnai and Kuga are part of Atsuko’s unconscious, a sort of gatekeepers between the reality and the unconscious world.

Equally interesting is the idea that these two bartenders don’t belong to Atsuko’s subconscious, but represent the portal from which her patients Noda/Konakawa enter their own dreams, as the film suggests. In that case, perhaps that is the reason why the characters in the book are so unbelievable. Maybe the entire novel is a collection of dreams from different characters.

That would truly be mindblowing, and if I were more confident about this interpretation, I would need to revise the star rating and Bizarrometer score. However, I’m not sufficiently confident to put it forward as the main theory, which is why I relegated this section to a curious afterthought.

Still, I’m convinced that there is much more to these two characters than meets the eye, and would love to hear your thoughts about this matter!

Dream-related weirdness aside, the premise of the book is rather straightforward: bad guys take possession of a dangerous dream-intruding device that they use for their own nefarious purposes; heroine enters the scene with her intellect, tenacity and ravishing beauty to teach the bad guy a lesson and restore order; bad guy is defeated; heroine is praised and rewarded and marries the nerd of the story. Of course, the author brings surreal elements into the story, adding an extra layer of complexity and appeal.

As our characters use and abuse the DC Mini technology, a continuous battle for dream control unfolds, in which they gradually begin to unlock hitherto unknown functionality, such as the capability of reading dream thoughts of other dreamers, invoking dream images into reality and even teleporting their dream alter-egos to the waking world.

Dream and reality begin to conflate, and more dangerous side-effects begin to appear, particularly the risk of falling into such a deep sleep that prevents the dreamer from ever coming back to the waking world.

In the end, however, Paprika and friends prevail, and, somewhat abruptly, the order is restored.

Sure, there is plenty of action and the dream sequences are truly creative and full of awesome imagery, but, unfortunately, that wasn’t enough reason for me to give a better rating. The two parts that make up the novel are somehow disconnected and the various sub-plots add little to the principal, more interesting narrative.

The dream theories Paprika draws on for her dream analysis (e.g., Freud’s and Jungs theories) are only very casually considered, and there seemed to be no attempt to connect them to the main dream battle events.

But, who knows. Perhaps I completely missed the deeper meaning of the book, particularly if my suspicion of a more significant role of Jinnai and Kuga in the story turned out to be correct. If that is the case, oh well… you cannot win them all. 😉

The dreamworld is surely an exciting, vibrant and bizarre realm.

It comes as no surprise then that dreams have been a source of inspiration for many creative works of art.

For example, Dali was clearly inspired by dream imagery when he painted some of his most famous works (e.g., the persistence of memory), and many important scientific discoveries were allegedly forged during dreaming.

I cannot help but wonder if Yasutaka Tsutsui also took inspiration from his own dreams when writing the dream sequences of Paprika…

See you in the next article!

Leave a comment

Add Your Recommendations

Popular Tags