This post is comprised of different sections

Take a look at our review of Memento!

Learn more about memory formation and retrieval!

This post is comprised of different sections

Take a look at our review of Memento!

Learn more about memory formation and retrieval!

Director: Christopher Nolan

Producer: Suzanne Todd, Jennifer Todd

Writer: Christopher Nolan

Starring: Guy Pearce, Carrie-Anne Moss, Joe Pantoliano

Year: 2000

Duration: 1h 53m

Country: U.S.A.

Language: English

Our rating

Your rating

When you watch a movie, it’s normal to expect a certain logic in how the storyline progresses. There is a beginning, a middle and an end. The storyline flows in a direction that doesn’t require the viewers to spend enormous brain processing piecing the sequences together.

These are “rules” that most cinematographers adhere to, and which we usually take it for granted.

Memento is an exception to this “rule”.

And I have to admit that the first time I watched Memento, it was a somewhat uncomfortable experience.

Because I watched the film shortly after it came out of the cinema, I thought maybe the feeling I had experienced was the result of my admittedly limited and non-eclectic cinematographic experience at the time.

However, having re-watched it 20 years later I stand by my initial evaluation – it’s perplexing. And note that I don’t mean it as a criticism. In fact, I revel in movies that take me out of my comfort zone, and weird movies surely fit the bill.

But Memento isn’t the typical weird. As we will see below, putting the story in its correct temporal order and with a few educated hunches, it is actually relatively easy to piece together.

As you will have noticed if you’ve watched the film, the weirdness comes, ironically, from the toll it takes on our working memory.

In this article we explore why that is.

Memento stars Guy Pierce as Leonard Shelby. One night, two thugs break in the house where Leonard and his wife, Catherine, live. The thugs rape and murder Leonard’s wife. Leonard manages to shoot one of the thugs dead but a second thug hits him on the head and escapes. The trauma to head causes permanent brain damage, and, as a result, Leonard cannot make any new memories. He decides to avenge his wife’s murder by tracking down the second thug and kill him, resorting to notes, tattoos and Polaroid photographs to keep track of his investigation.

The film is presented in reverse order: the first scene of the film is the last event of the story in its correct temporal order, whereas the last colour scene of the film is supposed to be the beginning of the story in its correct temporal order.

The black and white sequences are the beginning of the timeline and are presented in the correct temporal order. The last black-and-white scene merges into a colour scene (when Leonard kills Jimmy Grants). The story then progresses backwards until the very first scene of the film (Leonard shooting Teddy).

Even though the film is often described as having a non-linear narrative, it really isn’t. The story happens to be quite linear (each scene depends on the events of both the preceding and the following scene), it’s just presented in reverse order.

The team used an interesting blend of cinematographic techniques. The cameras follow Leonard around wherever he goes; and the way he rummages through pictures and documents while we hear his thoughts makes it all a very intimate viewing experience.

Even the palette of the picture was carefully considered. It appears, Nolan expressed the wish to turn the film all blue, but in the end, the production team decided to use more hues to make it look more realistic. Nevertheless, the amount of colours utilised was greatly restricted, thus leading to a perfect compromise between realistic scenes, but at the same time, a feeling of lacking.

And I loved the idea of presenting the film backwards!

Nolan apparently spent months trying to figure out how to bring the audience into Leonard’s point of view. He once said: “How do you give the audience experience of not being able to remember things? […] One day it occurred to me that all information could be given to the audience through the protagonist. […] The way to do that is to structure it backwards”.

The reversed scenes are such an ingenious technique, that I wonder why on earth hasn’t anyone thought of something like that before.

But Nolan was truly audacious. Just imagine the amount of resistance he must have felt when presenting his idea. It would be as if someone had thought of a crime/mystery film where you already know who the murderer is. How would a film like that even work?

But Memento does work. The storyline is so well-devised that the most interesting events were placed at the beginning of the storyline (i.e., at the end of the film). If you think about it, this is very odd, since the climax of a story is usually reached when a certain progression has built up.

Since we know from the get-go that Leonard killed Teddy (who he believes was his wife’s murderer), the viewer is left puzzled and conflicted as to what led Leonard, an amnesiac, to specifically target Teddy with such conviction.

Clues to Leonard’s reasoning are only given at the end of the film, thus resolving the viewer’s conflict and providing him/her with a sense of completion.

Brilliant!

If you’re lucky to be watching the film for the first time, I think now is just as a good of a time as any to watch it. Memento is one of those films that does not age.

What’s more, Memento was Nolan’s second feature-length film, so for a relatively inexperienced director at the time (2000/2001), Memento was a terrific achievement.

Here at Mindlybiz, Memento gets a star rating of 5.

As I mentioned above, Memento’s story is not difficult to understand. Contrary to how it’s often described, Memento’s story is quite linear, only presented in reverse chronological order.

True that there can be at least two competing interpretations about who Leonard really was and what really happened to his wife. However, none of them is less “correct” than the other. As you’ll see, most of the clues supporting either interpretation are presented in the film in one way or another. In the end, it’s up to the viewer to determine which interpretation feels right to him/her.

Because of this reason we decided to give Memento a Bizarrometer score of 2.

As the sequence of the film is presented in reverse, we know how the story ends from the beginning. Leonard kills a guy named Teddy, thinking he was the second thug that had murdered his wife, Catherine.

As the film unfolds in reverse order, we realise that Teddy is a corrupt cop who wasn’t actually involved in the murder of Leonard’s wife. Towards the end of the film, Teddy explains his version of the events regarding Leonard and the attack on his wife. A frustrated and confused Leonard then decides to frame Teddy for Catherine’s murder, even though Leonard is well-aware Teddy isn’t the actual assassin.

So, we are left with, at least, two competing interpretations:

Interpretation 1 (I1): Leonard witnessed the rape of his wife and attempted murder, but his wife survived the attack. Leonard was hit on the head, and the resulting injury caused his amnesia. An officer named John Gammel (a.k.a. Teddy) took Leonard’s wife case. He sympathised with Leonard’s ordeal and helped him track the thug that escaped, so that Leonard could kill him. Even though Leonard does kill him, he cannot remember that he did, so he never feels he’s avenged his wife.

Not believing Leonard’s condition, Leonard’s wife tries the ultimate test in which she asks him to administer insulin shots over and over again to see if he snaps out of it. However, Leonard cannot remember having already administered the shots, so she dies with an overdose. To escape feelings of guilt for accidentally killing his wife, Leonard represses this entire event, and unconsciously edits the whole episode in memory as if it had happened to Sammy Jankis, a conman who Leonard exposed during his days as a claims insurance investigator.

Interpretation 2 (I2): Leonard’s wife was raped and murdered by one of the thugs, who Leonard kills with his revolver. The second thug hits Leonard and escapes, leaving Leonard with anterograde amnesia. The police archive the case, dismissing Leonard’s account that a second thug ever existed. So, Leonard decides to avenge his wife’s murder, by pursuing the second thug on his own. With the help of police acquaintances he gets hold of the case file and identifies a drug dealer called John G as the thug that escaped. Leonard has been on the chase for John G. ever since.

Sammy Jankis was an actual amnesiac (psychological amnesia) whose insurance claims Leonard was investigated. Because Leonard ruled the amnesia as psychological (not physical) Sammy and his wife didn’t get insurance money, and Leonard got promoted. Sammy accidentally kills his wife with an overdose of insulin shots and ends up in a nursing home.

Arguing about which interpretation is the correct one is, in my opinion, a moot point. The reason being that they are both likely correct! Nolan was adamant not to give away his favourite interpretation, and I believe he purposefully injected some ambiguity into the film so that either interpretation could be equally valid.

So, in the end, it all boils down to which interpretation you fancy the most.

One thing is certain though: Leonard intentionally makes Teddy a target. He is probably convinced Teddy isn’t his wife’s attacker, but nonetheless goes ahead with the wicked plan to frame him for his wife’s attack.

Why does he do it? Again, it all depends on which interpretation you find more likely.

If you lean towards I1, then Leonard frames Teddy because he does not want to accept Teddy’s account of events, even though he might suspect he is right. Knowing that John G. is already dead makes him feel that his life has lost its purpose. Note that he could have simply written down everything Teddy had told him, with a note to find evidence to either corroborate or disprove Teddy’s version. However, he deliberately chooses to burn the photograph and completely discards these crucial pieces of information.

By always having a John G. to chase, ensures that his life has some meaning (as he mentions in the end of the film, “I have to believe my actions still have meaning. Even if I can’t remember them”).

If you believe I2 instead, perhaps Leonard is indeed certain that Teddy is lying about everything he has told him, and that one way to be sure that Teddy doesn’t interfere with his quest to find the real John G. is to eliminate him. Perhaps he even suspects that Teddy might be his wife’s killer, given that he is also called John G. (a fact, hitherto unknown to Leonard).

Before expounding on these interpretations, let’s go all sciency and talk a bit about memory.

Memory is really what defines us. It is because we can form, store and retrieve memories that we are able to understand, feel emotions and even move and speak.

But, and despite often being described so, don’t think of memory as something akin to a hard drive on your laptop. Memories are not perfect accurate records stored in one particular comparment in the brain like files on a computer’s hard drive.

In fact, memories are complex and extremely interconnected neural networks that spread over the entire brain.

Memories are also fragile and subject to change over time. A vivid memory of an event when you were 10 years old has most likely been altered over the course of the years. This may happen due to a combination of your own residual remembrance of the event, others’ account of the event, or even similar recent events that you might have experienced and got mingled with the older memory.

In the next section I’ll give a very brief scholarly introduction to the organisation of memory, and the division between long-term memory (the memory system that allows you to retain information over extended periods of time) and short-term memory (the memory system that stores information for brief duration).

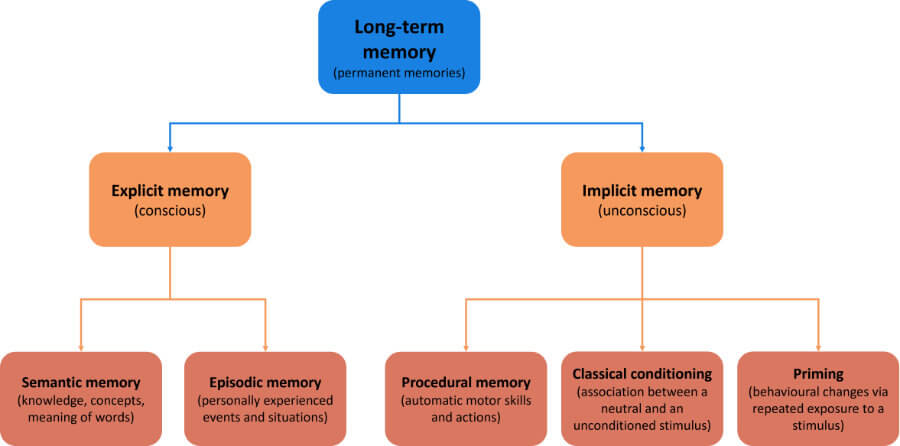

Every memory you have that goes back for longer than a a few minutes is most probably stored in your long-term memory, regardless of whether you are aware of them or not.

Cognitive scientists have found it helpful to divide long-term memory into two big sub-types: explicit memory and implicit memory. The difference has to do with the role of consciousness, that is, whether memories are being retrieved intentionally (explicitly) or automatically (implicitly).

Explicit memory are those memories that you can consciously and intentionally bring back and which can be expressed with language. That is why it is also known as declarative memory – because you “declare” (using language to describe) facts and events.

Explicit (or declarative) memory is further divided into 2 sub-types: semantic and episodic memory.

Semantic memory stores the memories you have of words, concepts and objects. For example, the meaning of the word troglodyte, the capital of France, the name of the object that you sleep on at night (bed), etc. Whenever you attempt to retrieve the meaning of any of these words you are using semantic memory.

Episodic memory refers to memories that you can consciously invoke and which you’ve personally experienced in some place and at some point in time. These include our own past experiences, thoughts and wishes (which together form the autobiographical memory), as well as memories in which we were simply witnesses (e.g., the memory of watching John fall down the stairs).

Note the important distinction between semantic and episodic memory: semantic memory doesn’t have a personal component (e.g., there isn’t anything you personally experienced when you’re simply trying to retrieve the name of the capital of France), whereas episodic memory does.

Implicit memory consists of memories which we can bring back without the aid of consciousness. This implies that you can “remember” something which you are not really aware that you have retrieved.

The prototypical example of an implicit memory is that of driving. You can talk to your friend seating on the passenger seat and listen to a good old song on the radio, all the while you are performing complex maneuvers on a busy city street.

Imagine the disaster it would be if you had to consciously focus on every single one of these driving actions. By the time you finished gearing up you could have missed the stop sign. However, you’re able to pay attention to the street, while your hands and feet do what they are supposed to do automatically.

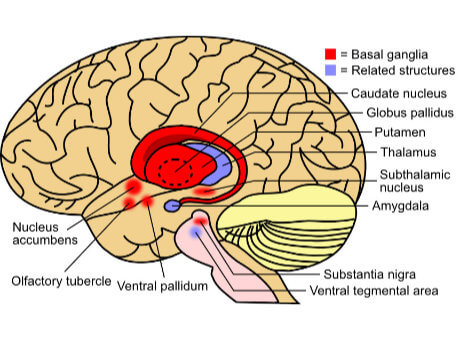

There are many types of implicit memory, but three of the most studied are procedural memory, priming and classical conditioning.

Procedural memories are related to motor skills learned through repetition, such as driving, tie a shoe or brushing your teeth. Once you have acquired the skill, these memories can be retrieved automatically, without the need to consciously supervise the action.

Priming is a phenomenon that occurs when your response to a stimulus changes because you have been exposed to it before. Imagine that during the day I bombard you with subtle cues that point to a specific number (e.g., the number 55), but are nonetheless unconsciously registered by your brain. Then, later in the day we are watching an American football match, and I ask you to pick any player, betting that I can guess the number of the player you’ll pick. Lo and behold, you pick the player with the number 55 – you’ve been primed! (btw, I took this example from the movie Focus, starring Will Smith and Margot Robbie – click here to see the scene, and here for the explanation why it worked).

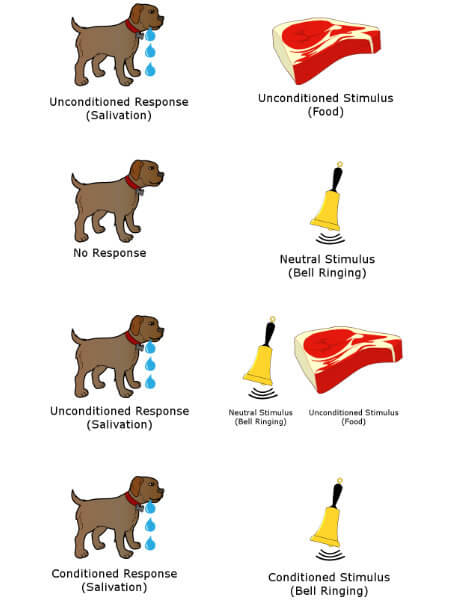

Classical conditioning is the association between a neutral stimulus (something which usually doesn’t trigger any particular response) and an unconditioned stimulus (something that leads to an automatic response, such as fear; see figure above). For example, let’s say someone gives you a shock every time a bell rings. The bell is a neutral stimulus at first, because on its own it wouldn’t normally trigger a particular response on you. However, if paired with an unconditioned stimulus (e.g., the shock), you might start becoming anxious every time the bell rings, even before you get the shock – you’ve been conditioned!

Both priming and classical conditioning are thought to be implicit memories because they can be retrieved relatively automatically and effortlessly. However, it’s still debatable whether implicit memory is truly an independent system from explicit memory.

Whereas the duration of long-term memories can last a lifetime, information in short-term memory can only be retained for about 15-30 seconds. If you can remember something that you have witnessed a few minutes ago, it is not in your short-term memory anymore but likely in your long-term memory.

Most explanations of short-term memory almost always use the example of keeping a phone number in mind. When someone recites you a phone number for you to dial in a few seconds, this information enters short-term memory.

For something to be registered in your short-term memory, you need to pay attention to it though.

So, if you are sitting in a cafe, and look at the person sitting next to you, it will be registered in your short-term memory. The menu you just read will be coded in short-term memory along with the typeface used, images, the commercial you see on TV, the name on the name tag of the waitress and so forth. Literally everything you give enough attention go through short-term memory.

Now, in every day life, it is more relevant to speak of a “working memory”, rather than short-term memory. The distinction is subtle but important.

When psychologists refer to short-term memory they are usually referring to the capacity of the storage: 15-30 seconds and up to 7 units of information (e.g., 7 numbers).

Working memory, on the other hand, is a brain system where you can process and manipulate information in short-term memory for a bit longer. If you are having a conversation with a friend, it’s probably useful to maintain information in your brain for longer than 30 seconds. Otherwise, you would always lose the thread of the conversation.

Most information that enters the brain will be forgotten. Tomorrow, you will have probably forgotten the menu, the person sitting next to you, the TV commercial and the name of the waitress from the day before.

Note, however, that forgetting things from the day before doesn’t necessarily mean they were short-term memories. They could have been momentarily transferred to long-term memory, but because the information wasn’t consolidated strongly enough in long-term memory, it was easily forgotten. Important memories (such as those carrying emotional content) tend to be transferred to long-term memory (see section below).

Note that although short-term/working memory is regarded as a separate system from long-term memory, it can interact with it by retrieving task-relevant information stored in long-term memory. Think about it: it would be very hard to follow a conversation about cars if you didn’t know what a car is. So, working memory needs access to semantic knowledge stored in long-term memory in order to make sense of the information.

You might wonder why have psychologists bothered using divisions like short-term vs. long-term memory, implicit vs. explicit memory and so on. Why not simply categorise everything in a single memory system and be done with it?

Researchers believe that the brain contains different memory systems that are more or less independent from one another. Many experimental studies with patients with brain lesions revealed that some types of memory are disrupted if specific brain areas are impaired.

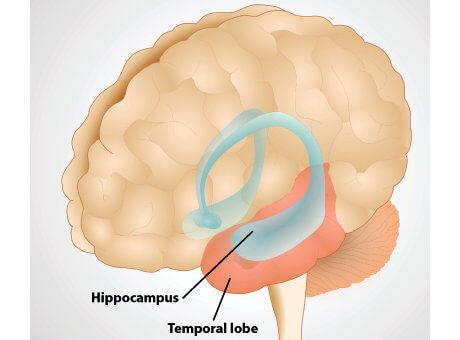

One of such brain regions are the medial temporal lobes. Famous patient H.M. suffered from severe epileptic seizures as a result of a bicycle accident as a child. In an attempt to alleviate and possibly cure his epilepsy, HM underwent a surgical procedure to remove both of his medial temporal lobes.

The procedure was successfully in controlling his seizures. Nevertheless, H.M. lost the ability to form new explicit memories: he could not remember any new information for longer than a few minutes.

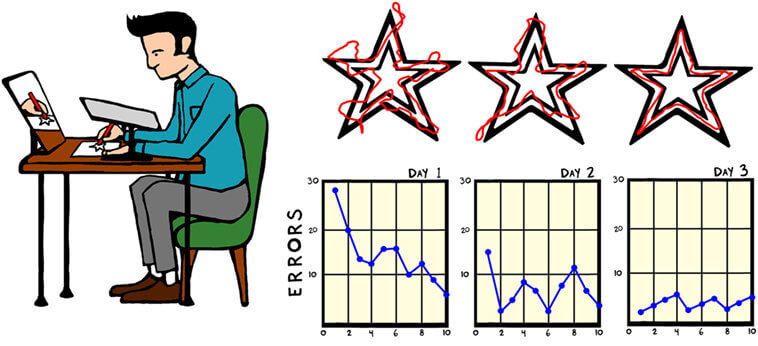

Surprisingly, his implicit memory was intact. Researchers asked H.M. to trace a line between two five-pointed star by only looking at his hand through a mirror (see figure above). With practice, his tracing got increasingly better over the course of the days, even though he was unable to remember that he ever did that task previously.

Likewise, his short-term/working memory remained intact. He could obviously follow the instructions the experimenter was giving, which is exactly the kind of job the short-memory is for.

So, H.M.’s memory deficit was in his long-term memory, more specifically, in his episodic memory (his semantic memory was partially affected). Whether his deficit was due to a failure during encoding, storage, retrieval, or a combination thereof is still a matter of much debate.

Cases such H.M.’s have helped researchers gain a better understanding of how memory is organised and led to the development of extant theories relating the structure and function of the brain to specific psychological processes.

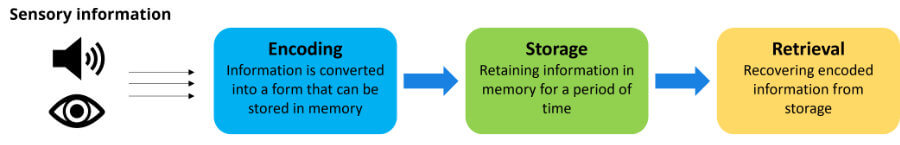

For a memory to go from short-term memory (memories that last for up to 30 seconds) to long-term memory, it needs to go through 3 stages: encoding, storage and retrieval.

Encoding refers to how the sensory inputs (e.g., the visual words in a menu) are converted to an input that can be stored in the form of a memory. Think about what happens when you press the “A” key on a computer keyboard. The computer doesn’t know if you typed an “A”. The pressing of the “A” key (sensory information) is converted into a digital signal that the computer (your brain) will understand.

Storage refers to the ability to maintain the information you just encoded. Keeping with the computer analogy, this would be equivalent in clicking the save button, so that a file is stored in the computer.

Retrieval is the ability to access the stored information whenever you need it. Again, using a computing analogy, this would be like going to the file and open it up so that you can read its contents.

Now, encoding, storage and retrieval are not discrete, isolated processes. In fact, encoding and retrieval are strictly intertwined, and the brain mechanisms responsible for each may overlap to a great extent.

If you direct your attention to a particular object, you will likely encode it visually and will bring the information to short-term memory. If you need to maintain that information for a short while it will be dealt with by your working memory. However, as discussed above, information in working memory is volatile, so it might quickly vanish (and most information we pay attention to is indeed lost).

However, if the information is deemed to be sufficiently significant, it will be stored in long-term memory (storage process). Consequently, you’ll be able to retrieve it if the information has been successfuly stored (retrieval process).

For example, if you have encoded a phone number just for the purpose of dialing it in the next few seconds, this information will be placed in short-term/working memory. But because this information is not really useful anymore, it will not likely be stored in long-term memory, and, therefore, you will not be able to retrieve it ever again.

In contrast, imagine you are walking down the street and someone steals your bag. Because of the significance of this event, your brain will give it a high priority and will transfer this memory to long-term memory (via the storage process).

It’s quite normal to forget things. As we age, we also show an inevitable decline in our ability to remember. This is a normal consequence of aging and even though gradual memory loss is inevitable, there are certainly ways to delay it.

Unfortunately, for some people, their memory problems are much more severe, leading to a complete inability to recover memories of the past or form new ones.

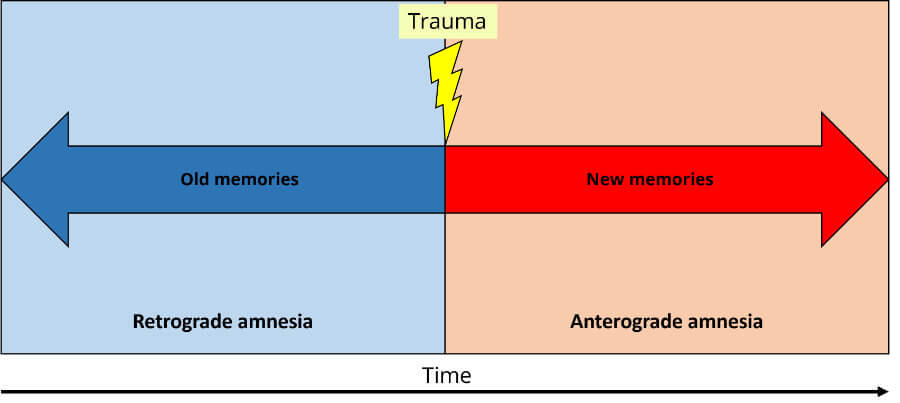

Neurologists have identified several types of amnesia depending on the type of insult to the brain and the extent of memory loss. In this secion, I’ll mention two specific types of amnesia: anterograde and retrograde amnesia.

If an individual is unable to remember events before the lesion, the patient will have retrograde amnesia. For example, H.M. was unable to retrieve any memories 3 years before the surgery, suggesting a partial retrograde amnesia.

If, in contrast, the individual is unable to remember events that take place after the lesion, then the patient will have anterograde amnesia. For example, even though Brenda Milner worked with H.M. for over 20 years, she always had to introduce herself to him, because he had absolutely no recollection of having ever met her.

Anterograde amnesia is by far more common than pure retrograde amnesia, and even rarer are patients with both forms of amnesia (such as patient H.M.)

Although H.M.’s amnesia was the result of a surgical procedure, amnesia can have other causes, for example, traumatic head injuries, dementia and encephalitis.

Finally, if the amnesia is accompanied by the presence of structural lesions to the brain (e.g., as a result of trauma to the head) it’s called organic amnesia. If there is no identifiable brain damage, then the amnesia is due to psychological factors (e.g., extreme stress), and it’s called psychogenic amnesia. Psychogenic amnesia is mostly associated with an inability to retrieve past memories (i.e., retrograde amnesia) but it can also affect the formation of new memories, although it’s extremely rare.

Memento is considered by many to be one of the most scientifically accurate movies with regards to the depiction of human amnesia. And for good reason.

If you read the section above about memory, you should be able to link some of the information I described with Leonard’s condition. Indeed, the memory impairment Leonard suffers appears to have been based patient H.M.’s condition as discussed above.

Many reviews and analysis I checked appear to suggest that Leonard has a short-term memory impairment. This is wrong. His short-term/working memory is just fine. As I explained in the section Short-term and working-memory, working memory deals with information at the short time scales (up to a few minutes if rehearsal takes place) and it’s what allows you to follow up conversations (which Leonard has no problem with).

Instead, Leonard’s memory issues come from the inability of his brain to transfer short-term memories to long-term memory storage sites (check out the section The 3 stages of memory if you haven’t done so). Information enters his brain, but never makes it to long-term memory; it stays in working memory for as long as he is able to hold it, but then it vanishes forever.

More specifically, it’s the transfer of newly-acquired episodic memories that is affected (see the section Explicit memory for more information). Hence, Leonard has anterograde amnesia. Because he can recollect events prior to the head trauma, he doesn’t exhibit retrograde amnesia (check out the section When memory fails: Anterograde and Retrograde amnesia).

I’ll start the analysis of Memento by describing the two interpretations that are the most obvious, and will also present the arguments that I believe corroborate either of them.

I’ll end the this analysis with an additional interpretation which, although rarely considered, is, in my opinion, a viable contender.

When you finish watching the movie, you will be probably wonder which of the two main interpretations is the correct one: what Leonard believes it happened on the one hand, and what Teddy reports to Leonard on the other.

In truth, I think Nolan’s idea was to leave sufficient ambiguity in the story such that either interpretation could be viewed as the correct one.

Here, I’ll detail both interpretations and why they both have points in favour and against them.

Just to recap the background story: Leonard Shelby was a claims insurance investigator, who enjoyed a promotion after he successfully solved the case of a certain Sammy Jankis who claimed to have anterograde amnesia. He lived a relatively peaceful life with his wife, Catherine, until, one night, two thugs break in the house where he ans his wife were living and rape Catherine in the bathroom. He wakes up and manages to shoot one of the assailants dead. However, he gets hit on the head by a second thug who had been hidden behind the door, and the head trauma rendered Leonard amnesiac. As a result, he cannot remember anything for longer than a few seconds.

According to Teddy, who describes this version of the events to Leonard close to the end of the film, Sammy Jankis was in fact a conman. He was faking his condition in order to get insurance money, but Leonard successfully exposed him and, for that reason, got a promotion.

In this version, Leonard’s wife was raped but survived the attack, although Leonard did become amnesiac as a result of the head injury.

Teddy was the officer assigned to Leonard’s wife case. He felt compassionate about Leonard’s ordeal, so he helped Leonard find the second thug (a certain John G.) the previous year. When they found John G., Leonard killed him, and Teddy took a photo of Leonard smiling after the fact (this is the photograph where Leonard is smiling and covered in blood).

However, due to Leonard’s condition, he doesn’t remember having killed John G (Teddy says: “But when you killed him, I was so convinced that you’d remember. But it didn’t stick. Like nothing ever sticks”). Teddy is a corrupt cop, so he decides to make a profit off Leonard’s condition by “helping” him to track other John G.’s (probably all drug dealers) and murder them, in order to keep their money.

Presumably, Leonard had already come across evidence that John G. was already dead. This fact was probably met with anguish, because it meant there was nothing else to do, no wife to avenge, no sense of accomplishment and justice again. So Leonard decides to rip 12 crucial pages of the police report of his wife’s case (which Leonard received from Teddy), so that he could create a puzzle that would always remain unsolvable.

Finally, Teddy also mentions that it was Leonard’s wife who was diabetic (Sammy Jankis didn’t have a wife). Leonard just invented Sammy’s story because he couldn’t cope with the fact he had accidentally killed his wife, so he repressed this entire memory.

So Leonard is deceiting himself. Every time he realises that there is no John G. to track down anymore, he chooses to dismiss the evidence and concocts another chase for the only purpose of having a purpose in life.

In this interpretation (which is Leonard’s view of the events), Sammy Jankis condition was real: he had indeed a car accident which caused his anterograde amnesia. He also had a wife, who, out of desperation for Sammy’s condition, asked him to administer insulin shots over and over again. When she died of an overdose, Sammy ended up in a nursing home. Although Leonard maintained he believed Sammy was truly amnesiac, he nonetheless ruled Sammy’s amnesia as psychological, not physical, and got promoted.

According to this interpretation, Leonard’s wife wasn’t diabetic. On the day of the attack, she was raped and murdered by the thugs. One of them hit Leonard and fled, leaving him with amnesia. Leonard has been looking for him ever since.

Leonard is an extremely unreliable narrator. That becomes evident towards the end of the film, when Leonard decides to frame Teddy simply because he disliked Teddy’s version of the events.

Check out these two thoughts of Leonard when he is about to frame Teddy:

– You think I just want another puzzle to solve? Another John G. to look for? You’re a John G. So you can be my John G.

– Do I lie to myself to be happy? In your case Teddy… yes, I will.

Leonard is pretty much admitting here that he’s going to frame Teddy even though he’s probably quite sure he isn’t the real John G.

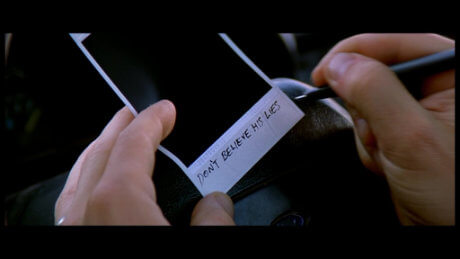

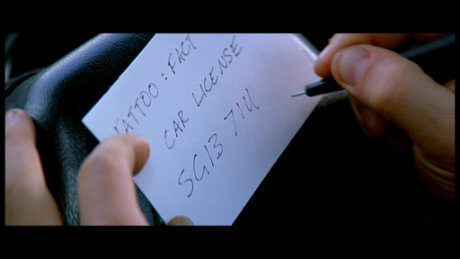

Moreover, instead of going straight to the point and write down that Teddy is his wife’s murderer, he decides to write “Do not trust his lies” on Teddy’s photo, along with his license plate, knowing perfectly well that these two clues will lead to making Teddy the next target.

What about the photos he burns (the photo of dead Jimmy and the photo of Leonard covered in blood and smilling)? Even if he did not believe Teddy, why would he burn those photos that may be clues to his wife’s case?

The only reasonable explanation for Leonard’s behaviour is that he does not want to come to the conclusion that Teddy is telling the truth. Burning those revelatory photos will ensure Leonard won’t investigate if John G. has already been killed.

Leonard even thinks: “Can I just let myself forget what you [Teddy] have told me?“

This entire scene really lends most of the proof that Leonard is playing detective and that he chooses to be incognizant about what trully happened with his wife and her attackers.

Furthermore, when Teddy begins to mention that it was Leonard’s wife who was diabetic, Leonard briefly recalls injecting the needle on her thigh, but then this memory is replaced by him pinching her instead. It could be that Leonard has been editing memories of his interactions with his wife, again suggesting he has been repressing every fact related to the fatal insulin shots.

In fact, during a conversion at the cafe earlier on in the film, Leonard discusses the problems of memory, not being an accurate storage of events as they happened.

Indeed, as discussed in the section The organization of memory, memories are very unreliable; vivid memories that we believe to be perfect mental records of events, will have actually suffered numerous changes throughout our lives.

But clearly the strongest case for I1 is the almost subliminal change of scene when Sammy Jankis ends up in the nursing home. During the close-up, Sammy shortly becomes Leonard. This could be a subtle clue that the two characters are indeed one and the same: Leonard.

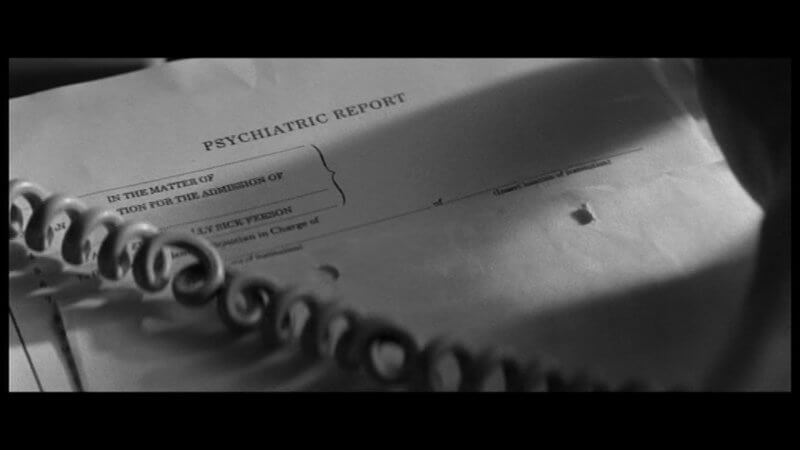

Finally, about 54 minutes into the film (during one of the grey scenes) Leonard gets hold of the police report of his wife’s case while talking to officer Gammel over the phone.

For a brief moment we see a document with the title “PSYCHIATRIC REPORT”. Note, that this brief of files were compiled by Leonard (even the police report, according to Teddy). Therefore, it’s not a stretch to think that Nolan included this psychiatric report among Leonard’s documents as a subtle clue that Leonard was at some point being treated by a psychiatrist – maybe during his stay at the nursing facility.

Teddy is a notorious liar. He lied he didn’t know Leonard, he lied Jimmy was John G., he lied he was a snitch, and so on. In sum, he lied pretty much the entire film. Is there any reason to believe that he is telling the truth about his version of Leonard’s story?

We could think that the story is just Teddy’s attempt to get out of a bad situation. Jimmy knew about Sammy Jankis, which made Leonard realise had he killed the wrong man. Teddy is suddenly confronted by a very angry and armed Leonard, and tries to get out of the situation by trying to manipulate Leonard’s memories into believing Sammy Jankis story is nonsense; that Leonard is the one with a diabetic wife, who he accidentally, but fatally, killed with insulin shots.

Let’s assume that I1 is correct: Sammy’s story is actually Leonard’s story and that it was Leonard’s wife, Catherine, who really was diabetic. In that case, shouldn’t Leonard remember that his wife was diabetic? Note that Leonard’s memory for past events is intact; he suffers from anterograde amnesia, which means that he cannot form new memories. However, his memories prior to the attack are intact (he doesn’t seem to suffer from retrograde amnesia).

I read some reviews suggesting that perhaps Leonard used conditioning to erase the memory that his wife was diabetic. However, this cannot be right: it is extremely unlikely, if not impossible, that conditioning alone would be sufficient to modify a long-term memory acquired prior to the lesion, let alone erase it.

Alternatively, you might argue that perhaps his wife became diabetic after the attack. However, how would Leonard know how to administer the insulin shots? He would have had to commit this learning to long-term memory first (the fact that she was even diabetic, where to find the medication, how to prepare the shots, etc.), before conditioning kicked in (as a side note, I believe this should be procedural memory and not conditioning as the film indicates, see the section Implicit memory).

There is also a brief scene where it appears that Leonard “recollects” injecting a syringe into his wife’s thigh. This sounds implausible. First, this would have to be a long-term memory acquired after the accident, which, as we have argued before, is impossible given his condition.

Alternatively, perhaps he changed the memory but, again, I find it unlikely. It would mean that he somehow was able to edit the memory and store it in long-term memory, which is unlikely given Leonard’s inability to form new memories. Even though, editing an existing memory likely presupposes a different brain mechanism than storing newly-acquired long-term memories (and, thus, the former process could be spared in Leonard’s case), it’s much more likely that Teddy was just trying to confuse Leonard.

Another potential problem for I1 is the fact that Leonard’s accounts when he was working as a claims investigator are so detailed and logical that is hard to believe that he is making it all up. If so, wouldn’t it be strange that he completely forgot the case that was pivotal in launching his career? Unless you have some obvious brain impairment, emotional memories (and no doubt this would be one of those) remain very vivid and are hard to erase or alter. Since this case purportedly happened prior to his injury, why would he completely erase from memory the most significant case of his career?

The most convincing piece of evidence is that split-second image where Sammy Jankis is replaced by Leonard in the nursing home. Well, if Sammy’s story is indeed a portrait of Leonard’s story and Leonard did end up in a nursing home, why on earth would he leave? Who took him from there, and for what purpose?

I wasn’t planning to add an additional interpretation, since most of the sources I perused analysed the film using either I1 or I2.

However, I could not resist mentioning a third, not too implausible interpretation: the idea that Leonard is faking his condition, that he can actually remember events, and/or that he might even be a psychopath.

Initially, I found these ideas over-the-top and quite easily refutable. For example, there is a scene when Leanord is running away from Dodd. He doesn’t know if he is actually running from him or chasing him, so he takes his chances and runs towards him. Bad idea! Leonard quickly realises that it is Dodd who is chasing Leonard with a gun, and almost kills him. Unless Leonard had a death wish, why on earth would he risk his life, knowing that an armed man is attempting to kill him?

Also, throughout the film, we can hear Leonard’s thoughts, and he behaves like a genuine amnesiac, even when he is alone in his room. Why would he pretend to have amnesia when he was alone?

But let’s entertain the possibility he is indeed faking it for a minute.

First, just because he knows he isn’t amnesiac, doesn’t mean he cannot fully commit to the role. That would surely fit the psychopath profile – they often pretend to be someone else quite convincingly. Perhaps he is religiously trying to behave and live like a true amnesiac, so that it becomes second-nature when he’s around other people.

Second, in the very last scene, did you notice how long Leonard was able to retain information in memory? Essentially, from killing Jimmy Grants until he arrived at the tattoo shop. And then he simply says “Where was I?” as if this is all just a game. It’s very suspicious.

Third, and this is perhaps the strongest evidence in favour of I3, there is a short scene at the end of the film when Leonard is lying in bed with his wife. Leonard has a tattoo on the left side of his chest that saying: “I’ve done it”.

The spot of this tattoo is the place Leonard is pointing out on the photo Teddy claims he took after Leonard killed the real John G.

There is no tattoo on this part of his chest shortly before this scene takes place. If Leonard is truly amnesiac, this cannot be a memory, since it happened after the incident, so he would be imagining it and that’s the end of it.

More relevant for the present interpretation however, if this scene is real (a quick peek to what will happen in Leonard’s life, not unlike post-credit scenes in the Marvel movies), the only conclusion we can take from it is that Leonard’s wife is still alive! Leonard kills Teddy and tattoos “I’ve done it!” on his chest and goes back to his wife.

Could it be that Leonard is trying to murder as many John G.’s as possible, just to make sure he will not miss the mark, given that he knows the thug who escaped is called John G.?

Remember, he didn’t know officer Gammel was John Gammel. He only got that information from Teddy shortly before deciding to frame him. Teddy goes: “Do you know how many towns? How many John G.’s or James G.’s?. Shit, Lenny I’m a fucking John G.”. Leonard had found his next target.

I’ll let that sink in now…

Memento is a truly mind-boggling film. The story is so obvious on the one hand, but incredibly fickle on the other, mostly because Leonard is such an unreliable narrator.

In this article, I focused on two main interpretations.

In Interpretation 1, Leonard’s wife was raped but survived the attack.

Not able to cope with Leonard’s amnesia, she decided to perform the fatal test Leonard mentions Sammy Jankis’ wife performed. She asked Leonard to administer insulin until she entered a coma and died.

Leonard repressed this memory and concocted the story of Sammy Jankis, who, in reality, had been a conman that Leonard exposed as a faker.

Teddy, the police officer in charge of the Leonard’s wife case, helped Leonard track and kill the second thug out of pity for his condition. Because he fails to remember he ever killed the actual John G., Teddy takes advantage of Leonard’s condition and uses him to kill drug dealers and get the drug money from them.

In Interpretation 2, Leonard’s view of the events, Leonard’s wife wasn’t diabetic and was murdered when Leonard tried to save her during the attack. Leonard believes the second thug is still on the loose.

Let me make something clear here. Neither Interpretation 1 nor Interpretation 2 is more correct or believable than the other. Both are supported by some events in the film and both can be refuted by other events. This was Nolan’s intention all along, and even though Nolan did have a favourite version, he left enough ambiguity in the film so that either interpretation could apply.

In fact, I guess that the two interpretations I focused on in this article are mere flavours of a much broader umbrella of possible interpretations. For example, I entretained another possibility that Leonard might even be faking his condition and/or be a psychopath.

Memento is one of those films in which its true meaning may be different in each and every one of us.

What else can I say? The idea of Memento is as straightforward as it is elegant.

With such simple techniques (e.g., showing the story plot in reverse, using short, delimited sequences) the whole cinematographic experience becomes so unique and personal.

Despite being a good two decades old, the film maintains its allure: it’s gripping, well-written, scientifically accurate and dramatic.

I mean, really, do you not sympathise with Leonard’s struggle? Do you not feel sorry for his inabiliy to follow through his actions? Do you not feel anger at the abuse and humiliation he constantly endures?

If your answer to these questions are yes, I’m happy I’m not the only one!

See you in the next article!

Masterpiece

amazing

amazing. 5-stars. blown away. great storytelling and structure. crazy twist, one of my favourite movies ever. youd never see it coming and its quite tragic when you think about it

Completely agree! Is there a particular interpretation of the ending you gravitate towards?

By the way, that was a very fitting name you have chosen 😀