This post is comprised of different sections

Take a look at our review of Mulholland Drive!

Learn more about Jung's dream theory and Jung's model of the psyche! Or check out the full explanation Mulholland Drive Explained!

This post is comprised of different sections

Take a look at our review of Mulholland Drive!

Learn more about Jung's dream theory and Jung's model of the psyche! Or check out the full explanation Mulholland Drive Explained!

Director: David Lynch

Producer: Mary Sweeney, Alain Sarde, Neal Edelstein, Michael Polaire, Tony Krantz

Writer: David Lynch

Starring: Naomi Watts, Laura Elena Harring, Justin Theroux

Year: 2001

Duration: 2h 27m

Country: U.S.A.

Language: English

Our rating

Your rating

It’s fair to say that Mulholland drive was the movie that not only changed my taste in art of any kind, but also very possibly my professional career. It was largely thanks to Mulholland Drive that I became interested in psychological thrillers, in particular those connected to the murky world of the subconscious mind. It turned out, this awakening was pivotal in choosing a profession as well.

I have to admit though, the first time I watched Mulholland Drive I was as fascinated as I felt stupid – I just didn’t get it! Thankfully, living in the Digital Age, a quick Internet search revealed numerous analyses of the movie that helped me appreciate the many subtle cues that abound in the movie. It gradually started to make sense.

If you strip away all the weirdness, the storyline of Mulholland Drive looks pretty elementary. I mean, here we have a girl, Betty, in her mid twenties moving to Hollywood with the aspiration to become a Hollywood actress.

She meets a woman, Rita, who is suffering from amnesia as a result of a car head-on collision. Betty befriends Rita and tries to help her find out about her seemingly shady past. In a separate story, a director called Adam is being bullied by an unnamed Organization into hiring an actress for the lead role in one of his movies. As we progress through the movie all three characters begin experiencing a series of bizarre and inexplicable events, which culminates in a story twist towards the end of the movie.

Nothing really exciting happens – there are no car chases, gunshot exchanges or jumping off cliffs. Yet, you can’t help but feel absorbed by the entire atmosphere; there is tension in literally every scene. Even the most mundane of behaviors, such as making a phone call, or walking down an alley, has a somehow edginess to it. Partly, this is due to the inclusion of just the right amount of cryptic events that make the movie weird but still largely coherent at the same time.

In my opinion, the ability to turn a seemingly simple narrative into a tale of eerie is one of David Lynch’s greatest qualities as a director. Even if you (like me) don’t get the movie the first time you watch it, by the time you finish it, you’ll beg for more.

The acting was superb. I knew little of Naomi Watts when I watched the movie back then, but I was positively impressed with what she managed to pull off.

I’m not an actor, but I don’t doubt that dual roles must be a tall order.

Yet, Naomi Watts played Betty/Diane as if she had been born for this role. I was captivated by the positivity and tenacity of Betty, whilst I pitied a troubled Diane.

Likewise, Justin Theroux was a pure joy to watch. My impression was that Justin needed not even memorize his scripts. It’s as if the cameras weren’t really there and he were simply going on with his life, and it happened to be a David Lynch’s movie.

And we mustn’t forget the soundtrack: every director knows that music is paramount to create that mystery and suspense that hook viewers to the screen, and Lynch surely knows how to hit the spot.

From the ominous score as Diane and Camilla walk up to the party house, to the poignant song of Rebekah Del Rio, every tune seemed to have been opportunely planned.

The same could be said of film production. Lynch had already given us a taste of his unorthodox film-making style (e.g., Twin Peaks, Blue Velvet), and we can definitely see the resemblance here.

Camera work, lighting and color blend in such a way, that the entire film has a kind of a dreamlike (or rather “nightmarish”) ambience.

Frankly, I cannot think how the film could be improved. I have probably watched it dozens of times and it never gets boring. Therefore, I am giving this cinematographic masterpiece a well-deserved rating of 5 stars.

As with most of Lynch’s films, Mulholland Drive is clearly on the weird spectrum. However, the weird elements in the film are so brilliantly incorporated into the narrative that they don’t become obtrusive.

Setting aside the pivotal story twist, there is a natural flow to the storyline, with only sporadic, although outright, bizarre scenes. For the most part, the narrative remains logical and you are able to follow the story without feeling totally perplexed. For this reason, Mulholland Drive receives a score of 3.5 in the Bizarrometer.

There are many interpretations for the main theme of the film, such as parallel universes to making deals with the devil (check this excellent source for copious interesting interpretations).

In this article, I will focus on the interpretation which I believe makes most sense. The idea is essentially this: the film can be divided into two parts; the first part we are viewing Diane’s dream – one in which she is a successful, kind and intrepid actress.

In the second part of the film, we witness Diane’s real life as a struggling and troubled actress. This divide is so obvious that you will notice when the jump from dreaming to reality occurs (see table below).

| Start scene | End scene | Movie order | Actual order |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pillow getting gradually blurry | Cowboy saying "Hey pretty girl! Time to wake up!" | 1 | 3 |

| Diane waking up and talking to her neighbour | Diane makes coffee and walks towards the sofa | 2 | 4 |

| Diane and Camilla making out on the sofa | Adam proposes to Camilla at the dinner party | 3 | 1 |

| Diane meets hitman at Winkies | Diane receives the blue key | 4 | 2 |

| Diane sitting on the sofa and staring at the blue key | Diane commits suicide | 5 | 5 |

There are many references to dreams in the film to suggest that this interpretation may have its merits. Here are a few examples:

1. The most telltale clue that we are witnessing Diane’s dream happens right at the beginning of the film, when we see an image of a pillow getting gradually blurred. It is likely that this represents Diane going to sleep, and what we see from then on is actually Diane’s dream. Notice how the walls are similar to those in Diane’s flat at the end of the film. The last twenty minutes or so, we are seeing Diane’s real life. This is also suggested by the cowboy saying: “Hey pretty girl! Time to wake up!”, with Diane waking up to the sound of the door bang.

2. If you re-order the sections of the film according to the purportedly “logical” chronology, you will notice that the order of events matches what you would expect if the first part of the film were a dream (see table above). After Diane wakes up and finishes making coffee she is wearing a dressing gown. You should also notice that the blue key that the hitman had given Diane at Winkie’s is on the table. However, a few moments later, we see Camilla lying on the sofa and Diane is wearing shorts. The blue key is not on the table any more (see the inset on the right picture above). So everything happening just after Diane and Camilla make out on the sofa, until the restaurant scene happens before Diane’s dream. The dream takes place after the hitman delivers the key to Diane. This makes sense: Diane could only have dreamed of the characters in the dream (e.g., Coco, the Cowboy, the waitress Betty, the guy at the Winkie’s counter) after she encountered them in real life.

3. Winkie’s scene: This scene is completely different from the rest of the film, and I couldn’t find any satisfactory interpretation of it. Here, there is a conversation between two men in the Winkie’s diner, which is the place Diane and the hitman meet. There are some interesting clues here, however, that might suggest we are in a dream. First, just before the Winkie’s scene, Rita falls asleep, and the Winkie’s scene with the two men develops. Straight after one of the men has a heart-attack, we see, for a split second, Rita still sleeping. Could this indicate that this scene is actually Rita’s dream? Perhaps this is a subtle clue David Lynch used to define the time frame of Rita’s dream. There’s more. One of the guys at Winkies says that it’s the second dream he’s had, but they are both the same – could the Winkie’s scene be a dream inside of a dream? As we will see later, they are both the same because Rita is simply a part of Diane’s personality – so it’s really the dream of the same person (i.e., Diane).

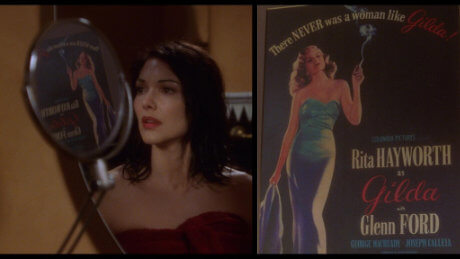

4. All characters that appear in Diane’s dream were individuals that Diane either already knew (e.g., Rita) or just met (e.g., the waitress called Betty) before the dream took place. However, most of the characters were given different names than their actual names (this is what psychoanalysts call displacement, and is a core characteristic of dreams).

Admittedly, none of these reasons prove that the film is about Diane’s dream, or that any dreaming occurs at all for that matter. This is, however, the classical interpretation of the film, and the one that makes most sense to me.

So, let me share with you one interesting theory put forth by Psychoanalyst Carl Jung, that attempts to explain why dreams exist and are so strange. Perhaps you can then judge for yourself the merit of our interpretation.

The Castigliane brother and the espresso

In the dream, Adam meets the Castigliane brothers, the two agents who order him to cast Camilla Rhodes for the leading role in his movie. One of the brothers tries an espresso, which he finds atrocious.

Diane spots this dream character at the dinner party while she is drinking an espresso herself. What’s more, a few minutes earlier, Camilla is heard saying “Yo nunca fue a Casablanca con Luigi“. Well, the name of the Castigliane brother that tried the espresso is Luigi Castigliane.

This suggests that Diane’s brain has fused these different elements (i.e., the sight of the man, the espresso, and the name Luigi) to concoct that scene in the dream. Because that dinner party turned out to be an emotional catastrophe for Diane, in the dream this negative emotional charge is released, as witnessed when the Castigliane brother spits out the espresso, and his sibling growls with fury.

Coco

Coco says exactly the same thing “Just call me Coco. Everybody does.” to Diane as she says to Betty in the dream. We all know from self-experience that the same expressions we use or hear in our daily life are often replayed in our dreams. Many of such repeated phrases abound in the movie.

Blue key

The blue key that Betty finds in her purse appears to be a sort of transformed version of the key the hitman gives Diane.

I have seen many interpretations about what the key could open, but my take on it is that the key doesn’t open anything at all. It is simply a code that the hitman uses to let Diane know that the hit took place. That’s why he laughs when Diane naively asks him what it opens – she is thinking about the key too literally.

In contrast, the blue key in Diane’s dream is full of symbolism. It opens a box that contains a void; this void could represent Diane’s unconscious.

The submerging into the void as the result of Rita opening the box may symbolize the transition from dream to reality, as it is at that point that Diane wakes up.

In a sense, the blue key that the hitman gives Diane kind of symbolises a transition as well. It represents the moment of Diane’s awareness that Camilla is now dead.

Adam and the pool man

At the dinner party, Adam is heard saying “So I got the pool and she got the pool man”. In the dream, Adam actually finds, to his chagrin, that his wife is cheating on him with a pool man. So Diane’s brain has altered the actual events in the dream, and this could indicate her wish to see Adam humiliated.

Bob Brooker: the director of “Sylvia North Story”

During the dinner party, Diane confesses she had been turned down the main role for a movie called “Sylvia North Story”, which she wanted really bad.

Diane also reveals that the director of the movie (a so-called Bob Brooker) did not think much of her, and gave the part to Camilla instead.

It is therefore interesting to see that during the acting scene in the dream, Bob Brooker is portrayed to be a seemingly inept director. Betty’s performance in the audition was flawless but the director appears confused and unsure what to say.

Again, this may indicate that Diane’s brain is attempting to fulfill a (perhaps unconscious) wish to ridicule the director towards whom she probably feels resentful.

In very broad terms, dream theories can be divided into psychoanalytical and physiological. In this article, I’ll focus the on a psychoanalytical theory of dreams developed by Swiss Psychoanalyst Carl Jung.

Before I do that, however, you cannot speak of dream interpretation without mentioning Freud, right?

I’ll cover Freud’s dream interpretation theory in detail in another article, but here is the general idea: Freud believed that dreams were the vehicle through which your childhood unconscious (mostly sexual) desires reached consciousness.

However, because of their disturbing content, they were being suppressed by an internal censor (a.k.a. Superego) and, along the process, transformed into something less disconcerting to the mind. In this way, you could go on sleeping without these disturbing wishes waking you up.

Well, Jung, a former disciple of Freud, disagreed with this idea. In simple terms, he believed that dreams were communicating important things that the unconscious wanted you to know, but that the conscious mind was too dumb to understand.

Before you understand why, let’s briefly discuss some of Jung’s main theoretical ideas.

Jung believed that over very long periods of time, the mind evolved particular “templates” that helped humans behave appropriately in a given situation.

He called these templates “archetypes”, and believed that they were common to every human being (I have them, you have them, your neighbor has them, and so on).

Here’s an example how one of these archetypes might have originated. Over time, our ancestors started to realize that mothers provided safety, food, and love. Over the course of several generations, this awareness resulted in the formation of the Mother archetype, which eventually got “imprinted” in the human mind. Once this imprint (the archetype) was created, every human being born thereafter inherited it.

This is very adaptive – a kind of a psychic natural selection if you like. Archetypes, according to Jung, could be even vital to survival in some cases. For example, shortly after you were born, you faced the situation in which interacting with your mother was required (e.g., because you wanted to feed). This situation activated the Mother archetype, helping you find your mother’s nipple (or cry if unsuccessful).

You are probably thinking that this sounds pretty much like instincts. Well, that’s because instincts and archetypes are two sides of the same coin. The difference is that instincts are physiological tendencies which can be observed as behavior. Archetypes, on the other hand, are like energy residing somewhere in your unconscious and they surface to consciousness in the form of images (for example, in dreams or art).

So, archetypes generate the instincts and images that influence our behavior without your awareness. Here’s something to think about: maybe you thought that an idea, which triggered a chain-reaction of associations, just spontaneously came to mind. But maybe, it was not spontaneous at all – maybe an archetype was activated that led you to that idea.

When and what type of archetype is summoned in your mind at any given moment largely depends on your current needs. In this sense, archetypes can be very adaptive, because if there is an imbalance in your psyche, archetypes will show you how to restore the balance.

For example, you needed to activate the Mother archetype pretty soon you were born, so this is probably one of the first archetypes you activate in your life. As we grow up, we are required to develop a social mask that helps us fit in in our society (think of the way you present yourself to your boss and the way you present yourself to your friends). This is the Persona archetype being activated (read more below).

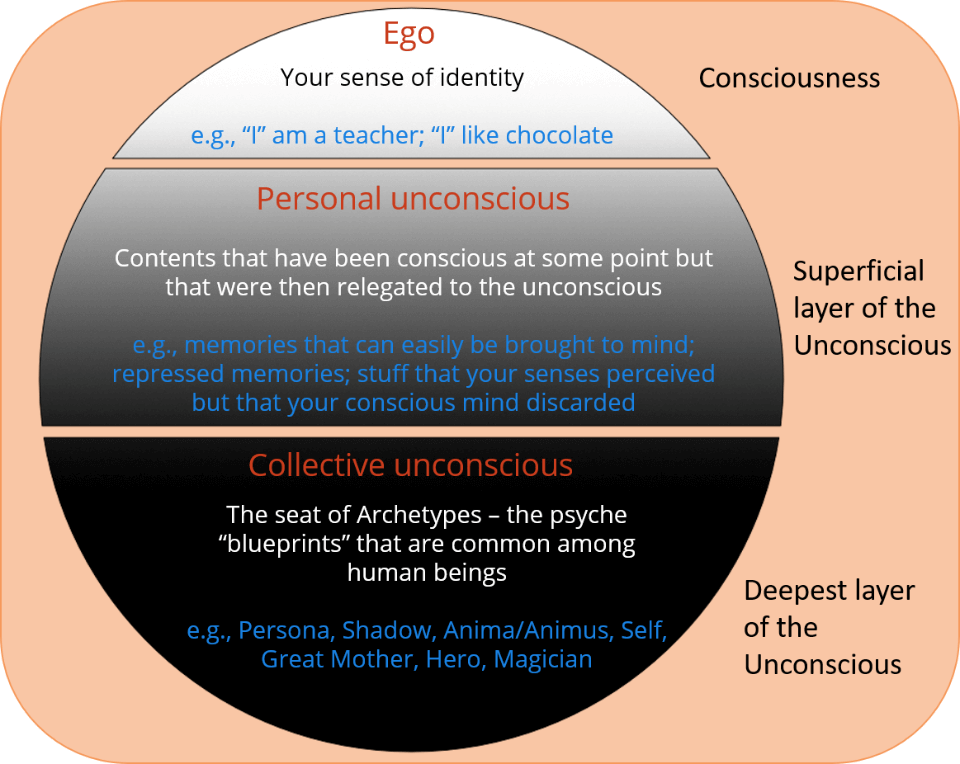

Archetypes sit in a part of the unconscious mind called the collective unconscious and have been sitting there from the day you were born. It’s called “collective”, because it is shared among human beings – we all possess the same kinds of archetypes.

In contrast, the personal unconscious is where all the repressed memories and mundane stuff that didn’t reach consciousness is dumped. The personal unconscious, unlike the collective unconscious, is unique to each and everyone of us. That makes sense right? My repressed memories are different from your repressed memories.

At the top sits the ego, which contains our conscious sense of personal identity (e.g., “I” am a teacher, “I” like chocolate, etc.).

OK, very cool you say, but why are archetypes relevant to dreams?

Well, Jung believed that one function of dreams is to compensate for certain conscious attitudes that are causing an imbalance in the psyche. And you guessed it: an imbalanced psyche is bad news!

Say you are focusing a lot on your career, and do not pay attention to your emotional life. Everyone would agree that this is unhealthy – we’ve got to balance work with having a life, right?

So, Jung’s reasoning was this: just as our bodies contain a self-regulating mechanism for when things start to go awry (e.g., if you are getting overheated you start sweating), dreams are one mechanism via which the psyche can be regulated.

Jung believed that whenever a particular conscious attitude grew too strong, the unconscious would attempt to restore equilibrium by invoking archetypes in dreams.

Let’s continue with the career example above. In your dream, the Mother archetype might show up in the form of a nurse that is caring for you. This could be a way the unconscious has to tell you that you need to be more caring to your kin for example, because a nurse is associated with attributes like caring, support, etc. If these messages are not paid attention to, neurosis, or even psychosis, may develop.

Note that during unpleasant dreams such as nightmares, archetypes can take a negative form, such as, for example, being chased by a hostile or threatening figure. These images, however, are still expressions of your own unconscious and should not be neglected.

In fact, these negative dream images offer you an opportunity to recognize aspects of your personality that you should develop. Heck, they might even give you hints on how to integrate them within yourself.

Say, for example, you dream that a terrifying witch is chasing you. No matter where you hide or how fast you run, she eventually catches you for nefarious purposes. A Hansel and Gretel kind-of plot.

So, the witch might represent the negative Mother archetype, and the dream might be telling you that you need to free yourself from the reigns of you possessive mother, and start becoming more independent.

As we grow up, we learn that there are certain norms we must adhere to if we don’t want to become the pariah. Children don’t really mind entering tantrum mode as soon as they are refused candy at the supermarket. With time, however, they will realize that these kind of actions are inappropriate, and will begin to behave according to societal expectations – this is your Persona developing.

So, we tend to develop social masks that suppress impulses which aren’t really acceptable in our society. This is how we present ourselves to the world – through different masks – and the Persona archetype coordinates this process.

These masks are largely advantageous, as they help you to flexibly adapt to whatever environment you find yourself in. For example, you might be a real practical joker (you know, placing drawing pins on the chairs of your unsuspecting and unfortunate classmates). If, however, you have landed a fancy, only-tie kind of a job, you’ll probably need to restrain yourself and keep your urges in check, especially when meeting your boss.

As difficult as that may be, you are essentially putting on a mask of a perfect employee whenever you meet your boss, because you want to get on his good side.

With your friends, however, your behavior is likely to be very different (you put on a different mask). So, the Persona archetype exists to help you fit in within the societal context you are in.

Note that your Persona combines not only those elements that you believe society expects from you, but can also contain idealizations of yourself (how you wish to see yourself), and how you want others to perceive you.

It’s also worth discussing the “ego” in the context of the Persona. The ego is everything you believe yourself to be, such as: “I like Pilates”, “I dislike Bob”, “I am a father”, etc. But don’t confuse the ego with the Persona. The ego is only known to you, whereas the Persona is oriented towards other people. In a way, the Persona is a creation of the ego, a kind of shield that hides the ego from its true nature.

Let’s say you are pissed off with your boss; this is the ego speaking: “I’m pissed off with my boss”. But because you need the job, you put on the mask of a good employee, so you act as if everything was fine (this is your Persona).

One problem arises when a person has a weak and under-developed ego. This person might start over-identifying with the Persona, believing that the mask he/she created defines his/her whole identity (in effect, the ego and Persona become the same).

Now, this is really bad because the Persona is very superficial, since it consists of a limited set of characteristics. For example, if you are a teacher and you over-identify with this Persona, you will start to condescend to your wife, kids and friends. So you might start giving them lectures and telling them what to do all the time, because it is your default way of behaving.

This is bad enough for interpersonal relationships, but what if you lose your job? Then your whole world collapses. You will feel lost, rigid and become psychologically ill as a result.

When you form your Persona (by trying to adapt to cultural norms), there are plenty of feelings, desires and ideas, that get repressed. All this “negativity” needs to go somewhere in the psyche, and the Shadow drew the short straw.

Shortcomings, perceived weaknesses, negative feelings or ideas and bad stuff we have done, thought and/or repressed are all dumped into the Shadow. So, the Shadow contains the elements of yourself that you do not want to include in your Persona, because showing the Shadow would be a source of shame and embarrassment.

According to Jung, however, it’s important to come to terms with the Shadow. Why? Because the Shadow is still part of us, and for Jung, the point of living is to become more who we are. We do this by integrating all aspects of ourselves, including our Shadow. Only that way we can be more authentic and complete.

If, on the other hand, the Shadow is not acknowledged, it will become denser and darker, and might eventually engulf your entire psyche, ultimately leading to serious psychological issues.

Note that your Shadow is unconscious – you are not aware that those negative traits belong to you. In fact, your Shadow tends to be projected onto others. For example, let’s say you find someone rather greedy, and you start feeling quite angry towards this person for the slightest comment he/she makes. However, it could be that what you dislike about that person is something within yourself that you unconsciously wished you did not have (e.g., greed). So, you are kind of projecting your own greed onto others, which is adaptive at first, but overdoing it will cause trouble in the long run.

You’ve certainly heard the phrase “embrace your feminine/masculine side”. Well, that pretty much summarizes the Anima/Animus archetype. In the classical Jungian sense, if you’re a man, you’ve got an inner Anima, or unconscious feminine traits; if you are a woman, you’ve got an inner Animus, or unconscious masculine traits.

It’s important to understand that “feminine” and “masculine” here refers to traits that, in conservative early ninetieth-century Switzerland, were commonly perceived to be either masculine (e.g., logical, intellectual) or feminine (e.g., emotional, loving).

Nowadays, most psychoanalysts consider this binary view of the Anima/Animus outdated and, instead, agree that every man and woman express both masculine and feminine aspects that vary along a continuum (e.g., so maybe you are 70% masculine and 30% feminine, or vice-versa).

So, according to Jung, we are psychologically androgynous (i.e., both male and female), which was a pretty radical thought at the time.

Similar to the Shadow, the Anima/Animus contain aspects of yourself that are not manifested in the Persona. This is because, as we grow up, we are encouraged to behave in a certain way, which is in accordance to our gender (think of the son playing swords, and the daughter playing with dolls – parents rarely encourage the exchange of these roles).

The Anima/Animus develops to compensate for this, and so, opposite-gender characteristics, which we are not supposed to show publicly (e.g., like being emotional if you’re a man), are repressed (i.e., sent to the unconscious).

Jung, however, believed that it was important to integrate the Animus/Anima (develop your masculine/feminine aspects) if you want to be true to yourself. This is a pretty important archetype, because it will form the basis of your future relationships with other human beings.

He linked the idea of Animus/Anima to the influence of parental figures. For example, a woman’s relationship with her father (or male caregivers) shapes the masculine image (i.e., the Animus) within her.

When she meets potential romantic partners, her Animus gets projected onto them, so she will choose a man that will be psychologically like her father. If the father was too strict, however, this woman might internalize criticism and a negative Animus will likely arise.

Now, if a woman starts to listen to the stuff the negative Animus is whispering to her in her subconscious, she runs the risk of Animus possession.

This is dangerous territory!

When you are not aware of the influence of your negative Animus on you, you will project it onto others (remember, projection is the unconscious placement of some part of yourself onto another person). You will feel that you are the one being criticized, which, as you can imagine, could be devastating to intimate relationships.

One important takeaway from all this, is that every archetype is present in everyone to some extent, and the entire human personality is the result of a complex interaction among all those archetypes.

Thus, different people will express archetypes with different strengths, although Jung still believed that everyone had a dominant archetype.

The main archetypes described above (Persona, Shadow, Anima/Animus) are considered quintessential, since we tend to rely heavily on them at several stages of life.

However, Jung and followers described myriads other archetypes (e.g., Magician, Hero, Lover, Ruler, just to name a few) that are summoned in various situations, and define some aspect of our personality.

If you have read the previous posts on the Jungian archetypes and his main structures of the psyche, you should now be a bit familiar with the core concepts of Jungian psychology, so let’s go back to the film and try to make sense of it in light of Jung’s dream theory.

One thing that I should make clear from the start is that all characters in Diane’s dream seem to be, in some form or another, representations of archetypal figures. In this article I’ll focus on the main characters.

Betty appears to be the manifestation of the Persona archetype. It is, therefore, no coincidence that Betty looks like Diane herself.

As alluded above, the Persona is one of the most important archetypes we possess, and it is through its influence that we present ourselves to other people. So, Betty is a manifestation of how Diane would like the relationship with Camilla to be like. Diane wishes to be the talented actress and having a dependent Camilla to care for – this is the mask (Persona) she also wants others to see, and how it is revealed to us in her dream.

There is a clue to suggest that Betty may represent this mask, which, again, is not her true self. When lady Louise Bonner knocks on Betty’s door and the two start conversing, Betty says at some point “My name’s Betty” to which Louise replies dismissively “No, it’s not. Someone is in trouble! Something bad is happening”.

I see this scene as an unconscious message, alerting Diane that “Betty” (i.e., Diane’s Persona) is simply a facade which needs to be disintegrated. Remember, the Persona isn’t really you, it’s a mask you concoct to conceal your true nature.

Diane may in fact (unconsciously) resent Camilla for the humiliation that she apparently has been enduring. For example, Diane mentions at the dinner party that once a film director didn’t think too much of her and favored Camilla over her for a role in a film that Diane was particularly fond of. Camilla also teasingly kisses the blonde woman at the party to perhaps purposely inflame Diane with jealousy.

The problem is that Diane might be over-identifying with her Persona – people with an under-developed ego may conflate their ego with their Persona. Diane’s whole world revolves around Camilla; Diane appears devoted to her.

But when Diane finally realizes that her love towards Camilla will never be reciprocated, her whole world crumbles and Diane becomes neurotic. All the subconscious hatred for Camilla surfaces and is projected to mysterious characters in Diane’s dream that want to hurt Rita.

Now, the theater and the Magician host warrants a few words.

The Magician archetype is one of the most interesting archetypes that exist – but it is also one of the most confusing.

The reason for this is that the Magician archetype shares many characteristics with several other archetypes like the Sage, Trickster, Healer, Innocent, and more.

In fact, you can think of the Magician as a conflation of these different archetypes, and it’s this interaction among archetypes that determines the qualities of the Magician.

Generally speaking, however, the Magician archetype is associated with mental agility (e.g., imagination, deep thinking, intelligence) as well as with intuition and insight.

As with all archetypes, the Magician can take both a positive (balanced) and a negative (under- or over-developed) form.

Positive Magician

If you possess a positive Magician, then you will be a person who has a highly inquisitive mind and thinks deeply. For example, you will be an avid learner, and revel in the pursuit of knowledge. Artists and scientists, for example, draw their insights from the positive Magician.

You will be able to adapt well to novel, and often unexpected, situations. If an obstacle crosses your path, you stop and reassess, look for a solution from different angles, consider the long-term consequences, and, finally, take the most appropriate course of action.

The Magician archetype is very much linked to your inner world. You will be a person that relies heavily on your gut feeling.

In society, a person tapping into the positive Magician will use these skills for the benefit of others. For example, they will want to share their knowledge without strings attached. I find online discussion sites a good example where you can find these kind of Magicians – experts in diverse fields are willing to help strangers despite receiving little or nothing in return.

Negative Magician

The negative Magician employs tactics that alter people’s perceptions (such as creating illusions) of himself and/or of others.

People with a over-developed Magician can be manipulative. This type of person uses his/her powers of insight to gather information about the people they interact with.

Contrary to the positive Magician however, they will use this skill out of self-interest. Think of the manipulator in a love relationship who is able to turn an argument around (of which he/she is culpable), but end up making his/her partner feel guilty.

At the other end of the negative spectrum, a person with an under-developed Magician has a rigid way of thinking, and will not be very open-minded. They will show a general disinterest in the questions of life.

This type of person will also not listen to intuition, as they wouldn’t comprehend warnings from their inner world.

They will also tend to be more impulsive and will have difficulties seeing the long-term repercussions of their actions (due to a lesser ability to use insight and intuition).

Balancing your Magician

Ideally, everyone should aim at developing a positive/balanced Magician. However, it is more likely that most of us possess a combination of some positive and some negative traits of the Magician.

The key, according to Jung, is to work on those aspects of ourselves that are not yet developed, and to try to bring them to a balanced state.

I think the presence of the Magician at the last stage of Diane’s dream is telling. Note how he keeps going on about everything being just an illusion and what-not.

What is he talking about?

Most people interpret this scene as yet another clue that nothing that is happening in the movie up to this point is real; that everything is simply a product of Diane’s imagination (or dreaming).

But perhaps there is a deeper meaning to that.

The few scenes we witness of Diane and Camilla’s relationship show a somewhat cruel Camilla that blatantly induces jealousy in Diane (e.g., ensuring Diane is looking when Camilla and Adam make out in the car), tries to reconcile (e.g., inviting her to the dinner party), only to engage in the same jealousy tactic all over again (e.g., kissing the blonde woman at the dinner party).

So, one possibility could be that the dream is attempting to let Diane know that she is being manipulated by Camilla, that Diane’s perception of their love relationship is nothing but an illusion.

The phrase “No hay banda” (there is no band) used by the magician could be a metaphor for “there is nothing there (i.e., no love)”, even if Diane wishfully thinks so (as the magician says: “Yet, we hear a band”).

Note how there seems to be a battle between the Magician and Betty. Only Betty’s chair shakes during the simulated tempest, clearly indicating that the whole theater scene is about Diane (who looks exactly like Betty). The fumes that emerge shortly after, appear to be a premonition of Diane’s death, as they resemble the fumes that appear after Diane’s suicide at the end of the movie.

Moreover, the melancholic song by the singer Rebekah Del Rio is a clear portrayal of Betty’s relationship with Camilla. As mentioned above, Camilla’s rejection was the tipping point to Betty’s breakdown, which is represented by the collapse of the singer.

So the dream theater scene is all about the relationship between Diane and Camilla. Diane’s unconscious is warning Diane that she needs to come to terms with her feelings towards an insincere Camilla, as this relationship is causing her to breakdown psychologically (remember, according to Jung, dreams are a tool the unconscious uses to inform you where imbalances in your psyche lie).

What’s more, when Camilla and Betty return home, Camilla calls for Betty who is nowhere to be seen. Betty vanishes leaving Rita alone to open the box, which seems to engulf her into darkness, at which point, a very disoriented Diane wakes up.

Could this scene symbolize the disintegration of the Persona/ego, perhaps triggering the psychotic episode that leads to Diane’s suicide?

Indeed, psychosis, according to Jung, occurs when the ego is too weak and loses control, letting unconscious contents flood the mind unabated.

Again, Diane’s over-identification with her Persona means that the Persona and ego are identical, and this causes her to neglect her true self. Diane’s realization of Camilla’s unrequited love, shatters her whole world.

With the dissolution of the Persona/ego, she falls prey to the dark side (the unconscious contents), which, in the movie, is represented by the submerging into the box.

One last thing about Diane/Betty. Post-Jungian psychoanalysts now believe that a damaged ego might come about due to a psychological wound from early childhood, perhaps as a consequence of not being accepted for who they really are (and, so, the need to behave in a way that is more acceptable to our parents or caregivers).

Close to the end of the film, Diane appears to suffer from paranoia and begins to have persecution hallucinations with the elderly couple that we see arriving with Diane at the beginning of the dream.

The contribution of the elderly couple, which is introduced in the film as being fellow passengers on the flight to L.A., is minimal and restricted to those initial and final scenes. However, the fact that they are the catalyst for Diane’s suicide, suggests that they likely played a critical role in Diane’s life.

My interpretation is that the elderly couple represents some parental figures (e.g., parents or grandparents), who, in reality, could have been critical, oppressive or even abusive towards her. In the dream, the elderly couple was displaced to the less emotional figures of fellow passengers that she has just met. Displacement is a common defense mechanism, according to psychoanalysts, in which a person that provoke anxiety is replaced by someone/something else that is less emotion-laden.

Recall the beginning scene when the limousine grinds to a halt and Rita addresses the chauffeur by saying “What are you doing? We don’t stop here.”.

Well, Diane is driven to the dinner party by the same chauffeur in that exact limousine (number plates are the same). What is more, when the limousine stops, Diane says the very same thing to the chauffeur that Rita said, and on the very same seat Rita was seating. This may suggest that Rita is another aspect of Diane’s personality.

Specifically, in the Jungian sense, Rita appears to represent the Shadow part of Diane’s personality. Remember that the Shadow contains not only all negative emotions and desires, but also weaknesses which may not fit into the ‘toughness’ that a person wants to incorporate into their Persona.

Rita is fragile, naive, insecure, needy – all unwanted traits that Diane would deem negative and does not accept as her own. Jung, in fact, believed that when we deny the Shadow of our psyche, we tend to project it to others (this is called Shadow projection).

So Rita is a projection of Diane’s own insecurities and shortcomings as a person. There is no one better to project those negative traits than to Camilla, as Diane feels humiliated and controlled by her.

Also, note how Rita is almost always wearing black – the Shadow archetype tends to show as a dark figure in dreams.

It is also interesting that Rita suffers from amnesia, which could represent repressed, unconscious traits stored in the Shadow.

The Shadow archetype in your dream tends to be someone you dislike in real life – well, Diane hires a hitman to assassinate Rita (!), so that pretty much ticks the box.

Jung believed that we must face the Shadow. Only then can the individual reintegrate it (learn to live with them) and find a balance between the Persona and Shadow.

I believe that Betty and Rita’s relationship is another desperate message of the unconscious that Diane needs to face her own Shadow, or else risk a psychological breakdown.

Consider the love scene. One interpretation could be that perhaps the psyche is telling Diane that she needs to come to terms with her Shadow (negative aspects of herself).

However, this process of Shadow integration seems to fail tremendously. Remember when Betty says she is in love with Rita, but Rita looks taken aback and does not say she loves Betty back.

I have always wondered what this could mean, and my interpretation is that the Shadow work has simply failed, and Diane has not managed to come to terms with her own repressed negative traits.

Dream-character Adam is a tough one to figure out. It appears that dream-character Adam inherited some of Diane’s misfortunes.

In the dream, Adam is humiliated by his wife; he eventually gets broke as his credit cards are cancelled; his job hangs on the line; he feels emasculated and capitulate to the demands of an unnamed Organization to make a certain “Camilla Rhodes” the lead actress in one of his films.

Adam soon realises that he has no control over this decision and is forced to say “This is the girl”. When Diane meets the hitman and shows him a photo of Camilla, she also tells him: “This is the girl”, suggesting that dream-character Adam might be another aspect of Diane’s psyche.

It is interesting that the dream-character Adam has to pick an actress called “Camilla Rhodes”. Once again, we are witnessing what psychoanalysts call displacement – that is, Diane’s wish of killing Camilla is being displaced by something less emotionally-laden – that of selecting a certain Camilla Rhodes for the main role in Adam’s film.

Fair enough, but what does Adam represent then? Perhaps Adam is another part of Diane’s Shadow – whereas Diane is projecting feelings of insecurity and fear onto Rita, Adam is that part of Diane’s personality which is submissive.

The limited scenes we see of Diane’s real life, show a somehow clingy Diane, who is incapable of standing up for herself – for example, when Camila and Adam make out in the car and Diane observes, or, at the party, when she appears to be laughed at by Adam and Camila.

So this attitude of being unable to stand up for herself is projected onto Adam, who in the dream is incapable of confronting the Organization, and succumbs to their wishes. Note how Rita and Adam never meet in the dream, it is as if Diane needs to come to terms to two separate aspects of her own Shadow…

Now, the unnamed Organization is composed of different male figures: the men at the meeting with Adam (the Castigliane brothers), Mr. Roque, the Cowboy, the mobsters and the hitman.

However, it appears that these characters are all unrelated as far as Diane’s reality is concerned. Diane sights the Castigliane brother and the Cowboy at the dinner party but they do not seem to be related. Also, the encounter with the hitman happens at Winkie’s, on the day after the dinner party, and nothing indicates that he is related with the other two.

However, in the dream, these people are brought together in the form of the unnamed Organization, which has an autocratic influence over the casting process of Adam’s movie.

Diane’s brain is using these unrelated events that occurred prior to the dream, linking them into a sort-of coherent dream story (not atypical of dreams).

Speculatively, there could be a hidden message in the Adam/Organization dream story.

Maybe Diane is convinced that Camilla and Adam are conniving with Hollywood powers. Or perhaps that they are themselves major players in this whole biased casting affair, which she fell victim of.

The absurd dream episode in which the Organization is forcing Adam into casting the girl could reflect Diane’s unconscious belief about the irrationality of Hollywood’s casting decisions, which might have contributed to her decision in having Camilla assassinated.

It’s no coincidence that Adam is forced to “cast” a certain Camilla Rhodes, which just happens to be the name of Diane’s love interest Camilla.

Again we are seeing text-book displacement at work here (remember, displacement is an aspect of the dream-work in that strong emotions associated with a significant person/object/idea in the dreamer’s life are rerouted to a less emotionally-charged person/object/idea in the dream).

Diane wishes Camilla dead but this thought is so disturbing that her brain replaces it with a more innocuous one: the process of casting an actress for a film.

Now, what archetype might the Organization represent?

My interpretation here is that the Organization symbolizes the Animus in Diane’s psyche.

The Organization is bullying and aggressive in its methods, which suggests that the Animus is manifesting itself negatively. Indeed, the negative Animus is likely to strike when some significant event shakes the woman (perhaps the realization that Diane is responsible for Camilla’s death).

When a woman identifies with the negative criticism from the Animus (Animus possession), the Animus tends to appear as a group of threatening male figures, that criticize, harass, humiliate and instill fear in the woman – all tactics employed by the unnamed Organization on Adam in the dream (and, remember, dream-Adam is part of Diane’s psyche).

Animus possession is possibly represented by Adam hiring Camilla Rhodes. When Adam says “This is the girl!”, a man who appears to be working for the unnamed Organization creeps from behind and nods his approval. This reveals that Diane succumbed to the negative Animus, which managed to retain its influence upon her life (also check out this forum thread where Diane’s Animus is discussed in greater detail).

Jung believed that psychological disturbance occurs when the unconscious mind is trying to make us aware of something in ourselves that we refuse to address. If we work with what our unconscious is telling us, we might stand a chance at integrating these not-yet-expressed aspects of ourselves and, hence, be more complete.

Dreams are a tool that the unconscious uses to tell you where you need to adjust your behavior, and it does this by summoning archetypal images. I see Diane’s dream as a desperate and, ultimately, futile attempt of the unconscious mind to warn her that she needs to work on developing her ego, and come to terms with her deepest, unconscious issues (her Shadow and negative Animus).

Fueled by constant humiliation from Camilla and Adam, coupled with a problematic upbringing (the reason for her weak ego), Diane’s unconscious is brimmed with rage and self-pity.

These negative emotions got projected onto the images of Camilla and Adam, whom she blames for her misery. This projection is never acknowledged (i.e., she never accepts her Shadow as an aspect of herself), and she is probably convinced that she is the victim.

Enticed by a harassing Animus (unnamed organization), unconscious material flood Diane’s mind, stealing her own identity (ego/Persona).

With the dissolution of the ego/Persona, there is nothing to hold her on to reality, and Diane becomes delusional as she succumbs to the contents of the unconscious.

Perhaps you feel the Jungian dream interpretation is spot on. Or perhaps you feel it is unduly far-fetched or even simplistic.

In either case, I will end this article by noting that Jung believed that the psyche has a reservoir of energy, which could be channelled into many areas of gratification, including creative and artistic activities.

He saw the creative/artistic process as influences from the personal and collective unconscious, guiding the artist not unlike a marionette.

So, perhaps the Jungian dream interpretation of the film makes sense not because David Lynch deliberately associated an archetypal image to each main character in the film, but simply because archetypal images were unconsciously evoked and incorporated into his work.

In a way, every film could be construed as the expression of the author’s unconscious. If the artist welcomes these unconscious impulses when producing an artistic work, the finished product will have tapped into the collective unconscious that we all share, and, in this way, will enable us to get a little bit closer to the artist’s mind.

See you in the next article!

Most of my research was done online where I picked up a few things here and there. However, the material below helped me greatly.

Books

Snowden, Ruth. Jung: The Key Ideas. From analytical psychology and dreams to the collective unconscious and more. Teach Yourself.

Gross, Phil. Jung: A complete introduction. Teach Yourself.

Youtube

I am particularly interested in what you’ve said about the ‘Organization’ as Diane’s Animus. It especially makes sense if Diane’s condition (illness?) is partly due to her having a ‘fragmented’ Animus – after all, the organization consists of several discreet entities, as you’ve described it.

The way I read Jung, the Animus normally consists of a series of male figures, each existing alone during the stage of animus development in which it corresponds. In Diane’s case, with more than one figure coexisting, perhaps the ‘Cowboy’ figure is a holdover from an earlier stage of Diane’s Animus, the cowboy representing a kind of primitive or ‘base’ male.

Hi Arlen! Great comment, many thanks!

I think your reading of Jung’s Animus is spot on. However, my understanding is that the Animus can appear as different male figures in dreams (even within the same dream). Jung mentions that the type of male figure will depend on the stage of development as you wrote, but it seems there’s no constraint on the number of dream figures that can appear, so long as they all represent that particular Animus stage (for example, a first-stage Animus can appear as Tarzan and then later as Superman in the same dream; but I’d say Tarzan and Gandhi in the same dream would be unlikely).

You do make a very interesting point that the Cowboy may have a prominent role in Diane’s psyche. This is consistent with him being the initiator as well as terminator of Diane’s dream, since he shows up shortly after Diane starts dreaming, and is the cause for her waking up from the dream (when he says: “Hey pretty girl! Time to wake up!”).

One important flaw in my interpretation is that I analysed Diane’s Animus as if she were straight, when in fact Diane is lesbian. Alas, Jung says little about Animus/Anima in same-sex relationships, so I decided to omit this point from my analysis. However, it would be interesting to discuss it further although I think that discussion will be more appropriate for the forum. If you like, you can start a new thread here, and I’ll be happy to dig up on this.

Hi mindbent, and thanks for clearing that up! I tried to make a new post just now at the link you provided, but I can’t tell if the post took or not. (I think I might have corrupted the block ‘footer,)

Hi Arlen

I’m very sorry but I can’t find your post anywhere in the website so probably it didn’t go through.

I performed a few tests just to ensure that the posts are shown and it seems to be working, so would you mind submitting your forum post here again please?

Thank you very much for your patience!

Hi mindbent,

I Just made another comment and it’s showing. Thanks for all your help with this.

For anyone interested, here is the link to the forum thread.

Masterpiece

None

None