This post is comprised of different sections

Take a look at our review of To the Moon!

Learn more about engrams! Or check out the full explanation To the Moon Explained!

This post is comprised of different sections

Take a look at our review of To the Moon!

Learn more about engrams! Or check out the full explanation To the Moon Explained!

Developer: Freebird Games

Publisher: Freebird Games

Genre: Adventure

Length: 4 hours

Year: 2011

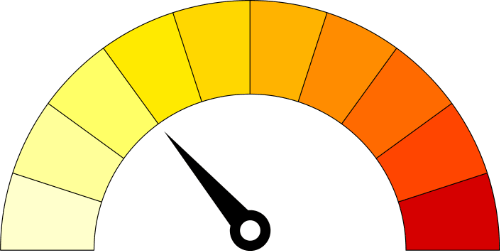

Our rating

Your rating

Not being a fanatical gamer, I do occasionally fancy playing a video game every now and then (do people still refer to computer/console games as video games, or am I already too old?).

Most games I played were during my childhood and early youth and, I’m sorry to say, they weren’t the sort of games you had to think much: Ninja Turtles, Unreal, Street Fighter, Fifa, Carmargeddon (jeez, I cannot believe my parents let me play that last one…).

But it would be Final Fantasy VIII that would make me realise that that not everything is Bang Bang Shoot Shoot, and that video games can come with awesome plots coupled with fantastic gameplay. But this is not an article on FFVIII (although that day will come, I’m sure).

On my quest to find mind-bending games, I came across To the Moon which was mentioned as a relatively weird game on several forums I had visited. Having read mostly awesome reviews on the internet and seeing the overwhelming positive ratings it received in gaming websites (8 out of 10 in Gamespot, 81 out of 100 in Metacritic, 4 out of 5 stars in Gamesradar+) I decided to have a go at it and initiate a new section in our website devoted to video games.

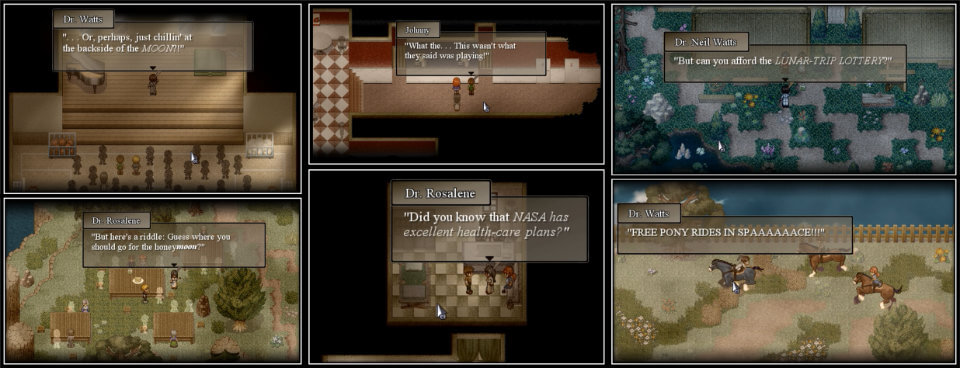

Dr. Eva Rosalene and Dr. Neil Watts are two scientists employed by a firm called Sigmund Corp. Their job is to use cutting-edge technology to infiltrate artificial memories into the brains of comatose patients, who would like their wishes fulfilled before dying.

The two scientists visit their latest client, a man named Johnny Wyles, who is in a coma, and who had previously expressed his wish to go to the Moon, even though he could explain why.

Dr. Rosalene and Dr. Watts embark on a mysterious journey to John’s mind. While perusing Johnny’s memories in order to successfully transfer the wish, they discover the disturbing reason for his lasting wish.

I agree with most reviews in that the story was indeed poignant and original. No doubt many emotionally-sensitive gamers will not be able to prevent shedding a tear or two, depending on how attached you become to the storyline.

By alternating between John’s past memories and the present, the game has a certain dynamism that I found appealing.

Now what I did not like.

First off, I wouldn’t really call this a video game. I mean it is a computer game of course, after all, I played it on my computer. But I didn’t reeaaally “play” it – I have books that require more interaction than this game, and they are still categorised as books.

In fact, if you go to YouTube and watch someone else play the game, you will not lose anything at all for not playing To the Moon… The fact is, there isn’t anything particularly exciting about the gameplay that should make the experience of playing it special or noteworthy.

Second, moving the characters around was a real pain sometimes. It’s a point-a-click game where you mouse click wherever you want your characters to move, but the mechanics are not the best in my opinion.

Third, there are a few puzzles to complete, but they are so laughably easy and soooo repetitive that you end up doing them just to be able to progress with the story. There is 0 fun aspect doing the puzzles after the third or fourth one.

Just for reference, I had more fun playing the whack-a-mole game (!) at the fair (one of the rare mini-games in the game) than I had playing any other puzzle. And the whack-a-mole game was pretty bad!!

Despite the good narrative structure, I also found the dialogues a bit bland and superficial. Given the game creators’ wish to concentrate on the storyline, I think this could have been improved (I’m currently playing Kentucky Zero Route, and I find the dialogues superbly intricate). Even the story itself appeared to me a bit over-the-top, mostly because it striked me as too unnatural.

For example, when John’s brother dies, their mother gives John beta-blockers, a type if medication for heart disease. The rationale was that it would erase memories of the accident and everything before that.

First of all, I don’t think beta-blockers affect your memories. I’m by no means an expert, but a quick wikipedia search has this to say:

“Adverse drug reactions associated with the use of beta blockers include: nausea, diarrhea, bronchospasm, dyspnea, cold extremities, exacerbation of Raynaud’s syndrome, bradycardia, hypotension, heart failure, heart block, fatigue, dizziness, alopecia (hair loss), abnormal vision, hallucinations, insomnia, nightmares, sexual dysfunction, erectile dysfunction and/or alteration of glucose and lipid metabolism.”

Second, how would the mother know that it would erase memories? In fact, and more to the point, how on earth would the medication affect only those memories that he’s supposed to forget, namely from the birth of his brother until exactly his death? What about memories of his parents? His name? Language?

Also, why doesn’t River say anything about their previous encounter when they are older? Clearly, she wants to, because she is constantly leaving hints behind. The explanation seems to be that she may have had Asperger’s syndrome, a type of autism syndrome disorder.

Still, it seems unlikely that River would not say anything at all. Instead, she uses very subtle cues for Johnny to figure it out for himself, forever if it came to it, even though this is causing extreme confusion, pain and suffering to both of them.

Don’t get me wrong, I found some of the narrative ideas very interesting – For example, I’m a very taken with the idea of localising engrams and building artificial memories; see below.

However, the strategy to keep gamers engaged was essentially omitting information from the gamer. So, the characters would talk a bit like this: “Oh, so you haven’t told her about that thing?”. “No, I don’t think she will react well if I mention that thing.” “Hhhmm, but she should know about the thing”. “Yes, you are right, the thing will eventually be brought up”.

Of course, I’m exaggerating, but you get my point. Mystery relied on blatant omission, sometimes rather forcibly, which I found a bit amateurish.

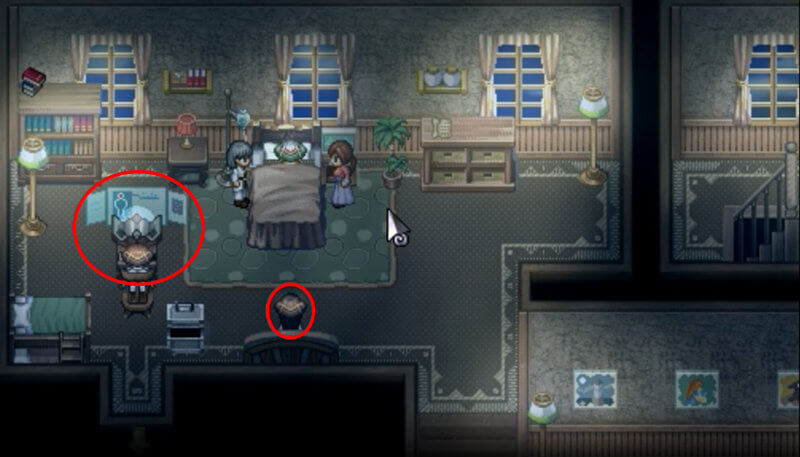

Moreover, the game is purportedly meant to evoke emotions and feelings. Well, if that was really the intention, then I think the game developers chose the worst medium possible. As far as emotional expressions are concerned (which is a potent emotional trigger), you can barely make up the face of the characters, let alone their emotions.

And, look, I have nothing against the 8-bit-kind-of graphics they used in To the Moon. In a way, I do have a preference for minimalist graphics. But, again, I simply do not think the graphics were adequate enough for the kind of emotional response the game was supposed to evoke.

I’m fully aware of the praise this game has received and I know my review will not come down well with some players… However, I really have a hard time giving this game a high score when I feel it lacks in so many crucial aspects to the gaming experience.

Again, I should stress it has nothing to do with the graphics. As I already mentioned above, I even tend to prefer simpler graphics if the focus is on gameplay and an engaging story. But that was the problem for me. Gameplay mechanics was very poor: lack of puzzles to solve, poor controls; the story, even though potentially interesting, suffers from weak dialogues and contrived plot.

Some players have noted that To the Moon feels more like watching a movie than playing a video game. If so, then we all surely agree this game is hardly a video game… Perhaps a new category should be created for “games” like these?

Personally, I wouldn’t recommend it as a video game, so here, at Mindlybiz, To the Moon gets a rating of 1.5.

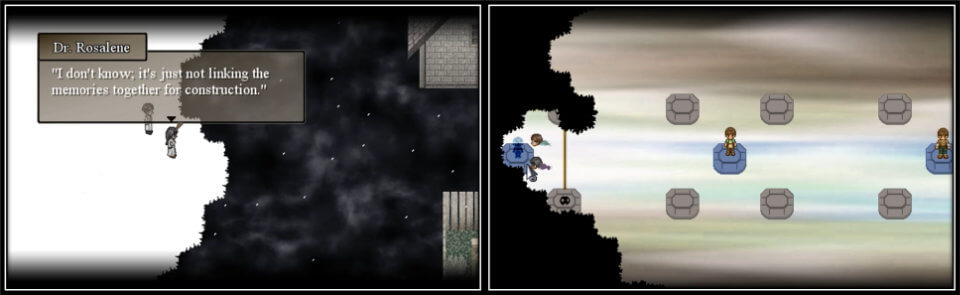

The game isn’t very easy to follow due to the fact that it is mostly being told in reverse timeline, with sporadic timeline jumps forward/backward. There are interesting bizarre moments, such as when the scientists tried to transfer the wish to the patient, but realise it did not work.

Furthermore, in order to create mystery, the developers omit important information which sometimes I found slightly forced.

Close to the end, there happens a major revelation that kind of places the entire narrative in context, so you won’t have the feeling something is left unexplained.

For that reason, To the moon gets a Bizarrometer score of 1.5.

Dr. Rosalene’s and Dr. Watt’s latest comatose patient, Johnny, has a last dying wish to go to the Moon.

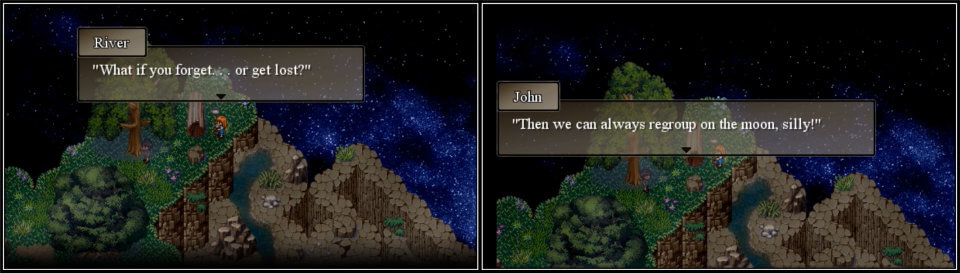

When Johnny was little, he met a girl called River at a carnival. The two got along instantly, and Johnny promised her that in case they ever got separated, they would regroup on the Moon.

A few days after the fair, Johnny’s twin brother is accidentally killed by their mother. To cope with the distress of losing her favourite son, she administers beta-blockers to Johnny, effectively erasing his memories up to a few days after the accident, including his encounter with River.

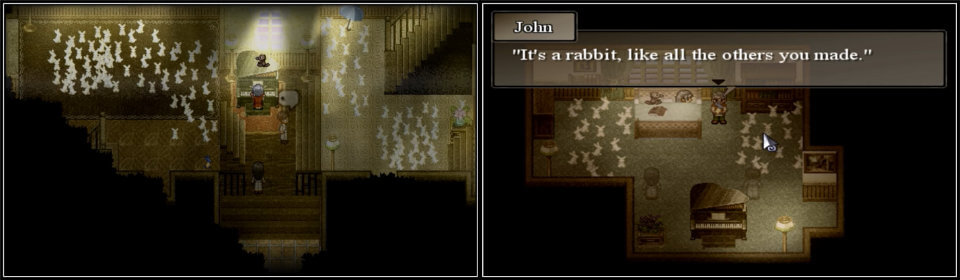

Johnny later meets River at school but doesn’t remember her. The two eventually get married, but River cannot cope with the fact that Johnny doesn’t remember her. She tries to jolt his memory by crafting paper bunnies (they played a bunny-related game in their first encounter), but to no avail.

When River dies of an undisclosed disease, her death triggers the resurgence of the (unconscious) promise that Johnny had made to River when they were children: that if they got separated they would meet on the Moon. Thus, because River died, Johnny has the inexplicable urge to go to the Moon.

After failed attempts to inject in Johnny the wish to go to the Moon, Rosalene realises that the only way that Johnny is motivated enough to go to the Moon is by removing River from Johnny’s memories.

Despite Watt’s protests, Rosalene’s plan is ingenious.

She knows that the machine works by using Johnny’s desire to dictate his behaviour. In other words, it will be Johnny’s own desires and motivations that will generate his new life – the machine is only a tool that makes this transformation possible.

Johnny has subconsciously registered the promise he had made to River to regroup on the Moon, and it is Johnny’s unconscious that drives this desire to meet River on the Moon.

River appears in Johnny’s new life, at a point where she is needed. This serendipitous encounter is no coincidence at all. It is Johnny’s unconscious and willingness to join River on the Moon that is driving his memory of River to NASA, exactly when he is being assigned a team to go to Moon.

To manipulate Johnny’s memories, Dr. Rosalene and Dr. Watts use a machine that appears to create, erase or modify the physical substrates of those memories. These are called engrams, and are the topic of the next section.

Have you ever stopped to think about how do you actually remember things?

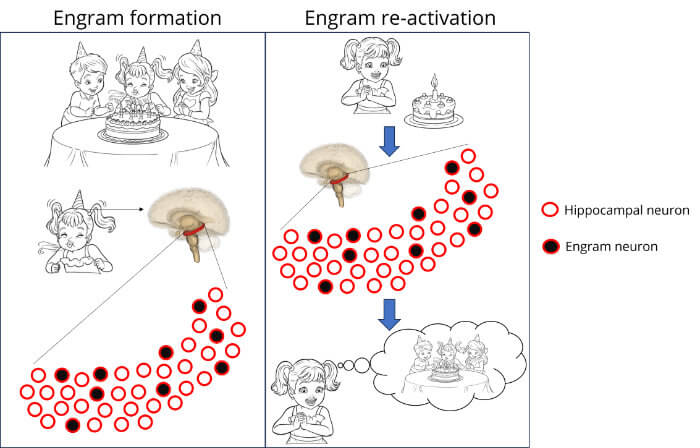

Think of your last birthday. Obviously, you aren’t literally reliving your birthday when you remember having met your friends and family and eating cake. So, what exists in your brain that allows you to have such a vivid mental image of that experience?

Strides have been made to answer questions like these, and research has unambiguously led to a particular construct: the engram.

To me, engram research is one of the most exciting topics in the field of neuroscience. Simply put, the engram is a neuronal representation of a particular experience.

More specifically, whenever you experience an event, that experience activates a bunch of neurons that encode that event in the brain. These neurons go through chemical and physical changes (e.g, strengthening of synaptic connections among neurons), forming what scientists refer to the “engram” – the physiological substrate of the memory itself.

Note that the engram is not synonym with memory. It simply provides the scaffold for a memory to emerge.

For example, a cue present during the encoding of the experience (e.g., seeing a birthday cake) can potentially reactivate the engram; only then will the memory of that experience (e.g., your birthday) be retrieved.

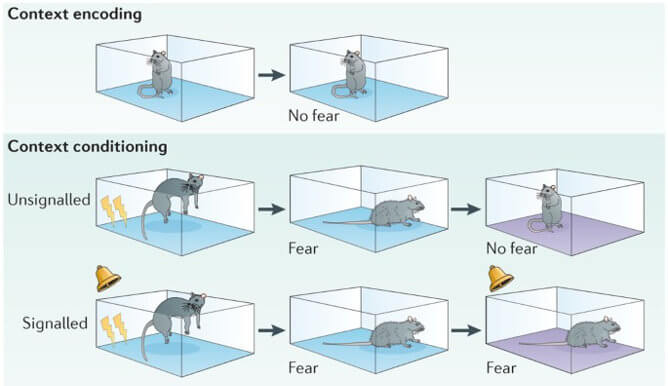

To understand how scientists have been able to observe engrams, it will be useful to explain a particular experimental set-up researchers use called the fear conditioning paradigm.

In this paradigm, researchers condition mice by repeatedly playing an innocuous stimulus, for example a neutral tone (what is known as conditioned stimulus, or CS) at the same time they deliver an aversive stimulus, such as a footshock (what is known as unconditioned stimulus, or US). The unpleasant footshock causes mice to freeze, which is an adaptive defense mechanism in prey animals.

By repeating this process a number of times, the mice will learn to associate the innocuous tone with the unpleasant shock, and a new associative memory (CS-US) will be formed.

After fear learning training, playing the tone in isolation (i.e., without the shock) is typically sufficient to see mice freeze in fear, showing that the new associative memory during the previous learning phase (i.e., the CS-US memory) has been retrieved.

Now, for the most part, engram research has been conducted using rodents.

In one study, researchers tagged neurons that were active during the fear learning training. They found that there was an above-chance overlap (about 11% overlap in the basal nucleus of the amygdala) between those neurons and neurons active when mice were re-exposed to the same conditioned context 3 days later.

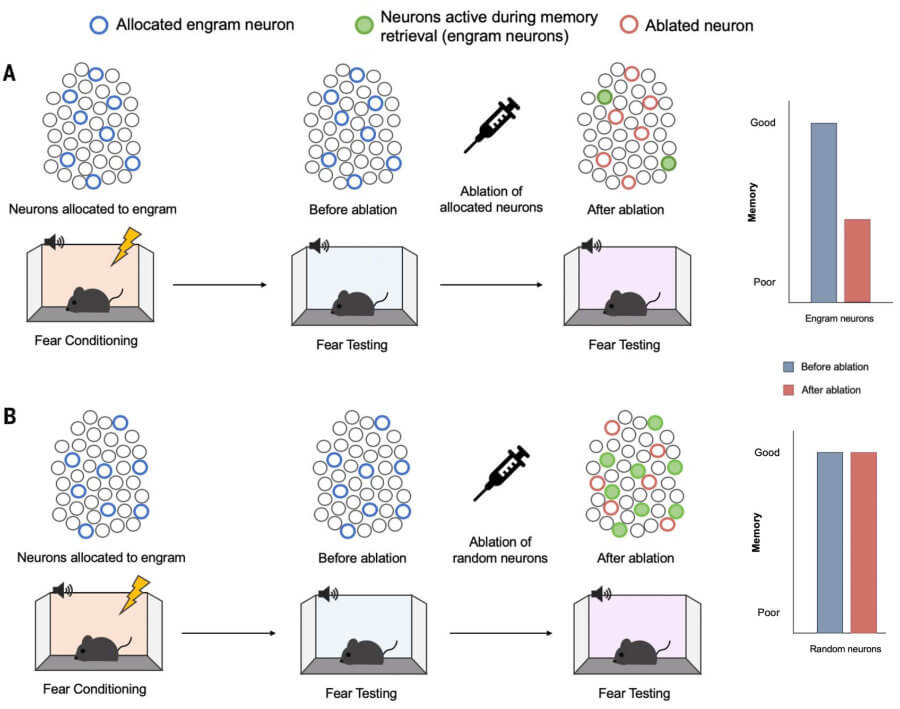

Researchers have also been able to manipulate which neurons will be part of an engram. In one study, a number of neurons were selectively allocated to an engram in mice while they performed the fear learning task. The mice showed the typical freezing in response to the CS alone.

Afterwards, those allocated engram neurons were eliminated (ablated). When the mice heard the CS tone again (which should have evoked the fear memory), they did not freeze. It was as though the fear memory had been completely erased.

To ensure that the lack of freezing response wasn’t just a general insensitivity, the researchers then killed a bunch of random neurons (those not allocated to the engram). Mice showed the typical freezing behaviour when the tone was replayed, suggesting that the disruption in the freezing behaviour mentioned above was specific to the elimination of allocated engram neurons.

You might have already heard or read somewhere that many algae and bacteria have photo-sensory molecules that can convert light into electricity.

Even humans do it to some extent. For example, our vision is possible due to the presence of a type of opsin protein (called rhodopsin) found in the rods of the retina. Light reaching your eye is converted into an electrical signal which is transmitted to the brain, allowing us to see.

Scientists have taken some of these natural proteins that can convert light into electricity, and manipulated them so that they can be inserted into neurons.

In most cases, the protein channelrhodopsin (ChR) is used, which is present in green algae and is sensitive to blue light. Thus, if a neuron contains ChR, blue light would stimulate that neuron.

In order to place ChR into a neuron, we need a bit of genetic engineering; that is, we change the genetic makeup of the neuron, such that it expresses ChR. To that aim, viruses can be used to infect the neuron and change its genetic expression in order to produce light-gated ion channels that react to light.

Once this has been done, if you shine light into those neurons, the light gets converted into electricity. Because neurons use electrical signals to function and send messages to other neurons, we can use light to turn on/off those neurons at our leisure.

Conversely, scientists can also inhibit, or silence, the neuron by exposing other types of protein to light (e.g., Archaerhodopsins).

The studies I reviewed above suggest the existence of engrams for actual experienced events.

But what if we could make use of engrams to generate memories of events that were not experienced by the subjects? In other words, can we implant false memories?

Recent optogenetic studies (see What is optogenetics?) on mice appear to suggest we can.

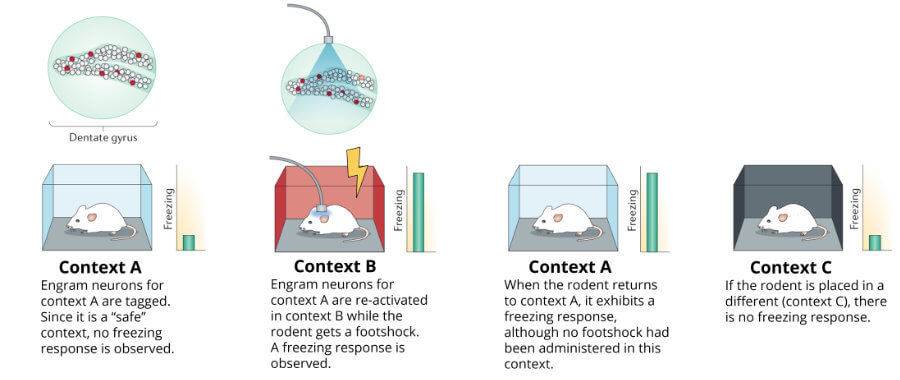

For instance, a team of researchers from MIT published a study in 2013 in the journal Science in which they let mice explore a particular environment (context A), while the researchers labeled engram neurons in two regions of the hippocampus (dentate gyrus and CA1; see figure above).

Then, the mice were put in a different environment (context B), where researchers administered uncomfortable footshocks. Critically, during this fear learning training, the researchers reactivated the engram neurons in the two hippocampal regions that had previously been labeled in context A. Reactivation was performed using optogenetics, a technique which uses light to activate specific neurons.

Next, the mice were placed back in context A, where, remember, no footshock had been administered.

What do you think happened?

Even though mice were never shocked in context A, they still froze in fear significantly above chance as soon as they were placed in context A.

Say what?!? Why would the mice freeze in the context that was completely safe??

The answer is that the activation of the engram linked to context A got associated with the shock during the fear learning phase in context B. So the mice formed a false memory: the memory that context A should be feared.

Importantly, when the mice were placed in a novel context (context C), they did not show above-chance levels of freezing behaviour, suggesting that the false fear memory was restricted to context A.

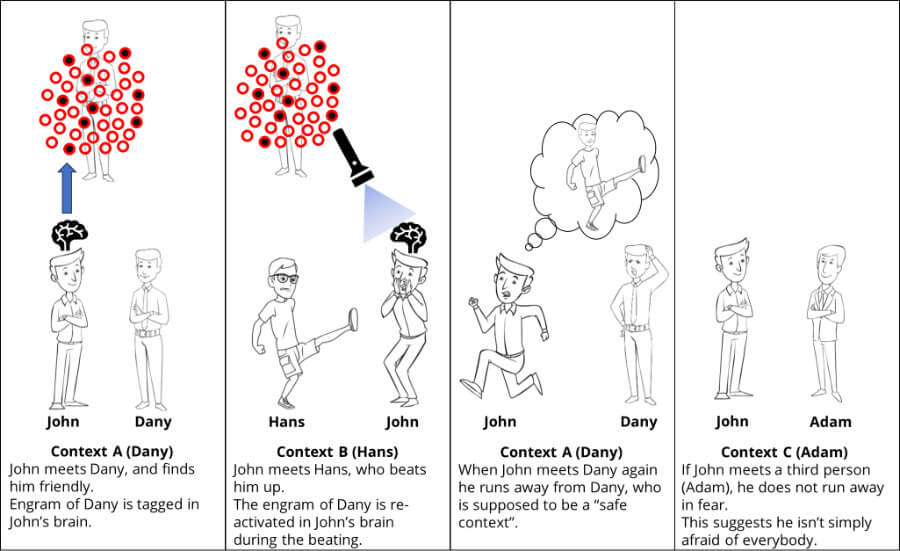

Let’s make this a little bit more tangible by imagining that, unbeknownst to you, you are the subject of a wicked experiment by a wicked scientist.

The scientist introduces you to Dany, who is friendly to you, making you feel safe around him. During this interaction with Dany, the scientist records your neuronal activity, and detects a collection of neurons that visually represent Dany.

Later, the wicked scientist introduces you to another person called Hans. Now, Hans is barbaric beyond belief, as you get repeatedly punched and kicked by him.

Now, while Hans is beating you up, the wicked scientist activates the previously recorded neuronal representation of Dany in your brain. The consequence is that you become convinced that Dany is physically attacking you.

When the wicked scientist places you together with Dany again, your behaviour is to immediately wet your pants. The reason should be obvious: you got beaten up pretty badly and, in your mind, that was the doings of Dany.

But, the scientist ponders, perhaps this has nothing to do with Dany specifically; maybe you are simply generalising your fear to pretty much every human being. To figure this out, the wicked scientist sets you up with another individual, Adam, who you appear not to fear.

The results of this experiment show that the wicked scientist has successfully implanted in your brain a false memory of Dany (and not any other person) as being the aggressor.

This is pretty much what researchers did to the mice (just not so violently as in my made-up and cruel experiment). Dany would be context A, Hans context B and Adam context C. The neuronal representation of Dany that the scientist tagged in your brain would be like the neuronal engram that was labelled in the brains of mice during the exploration of context A. And the beating would be the footshock.

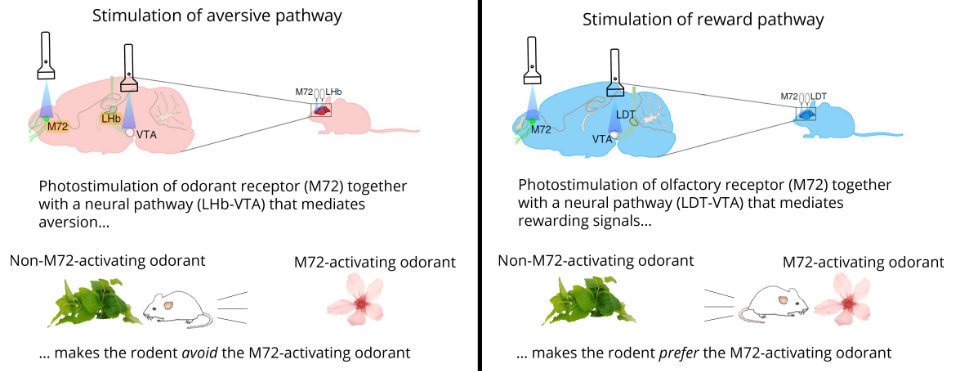

In all the studies I reviewed above, the mice underwent some sort of learning experience; even in the false memory study, mice were physically shocked in a particular environment.

Impressively, a more recent study showed that artificial memories can be made even in the total absence of experience.

Researchers used optogenetics (see What is optogenetics?) to stimulate a structure in the olfactory bulb, a brain region involved in the sense of smell, in the mice’s brain. Importantly, that brain region responded to a particular type of odor called acetophenone. This stimulation was paired with optogenetic stimulation of neuronal populations involved in either rewarding or aversive responses (see figure above).

After conditioning, mice showed a preference for the real odor when the rewarding pathway had been stimulated (right figure above), whereas they showed aversion to the odor when the aversive pathway had been stimulated (left figure above).

Remember, mice did not undergo any task or experience whatsoever, they sat idling in the lab. So the memory the researchers created was indeed fully artificial.

If engrams are damaged, they cease to exist. In that case, it will not be possible to access the memory ever again. Damaged engrams can result from traumatic injuries to relevant brain regions that encode said engrams.

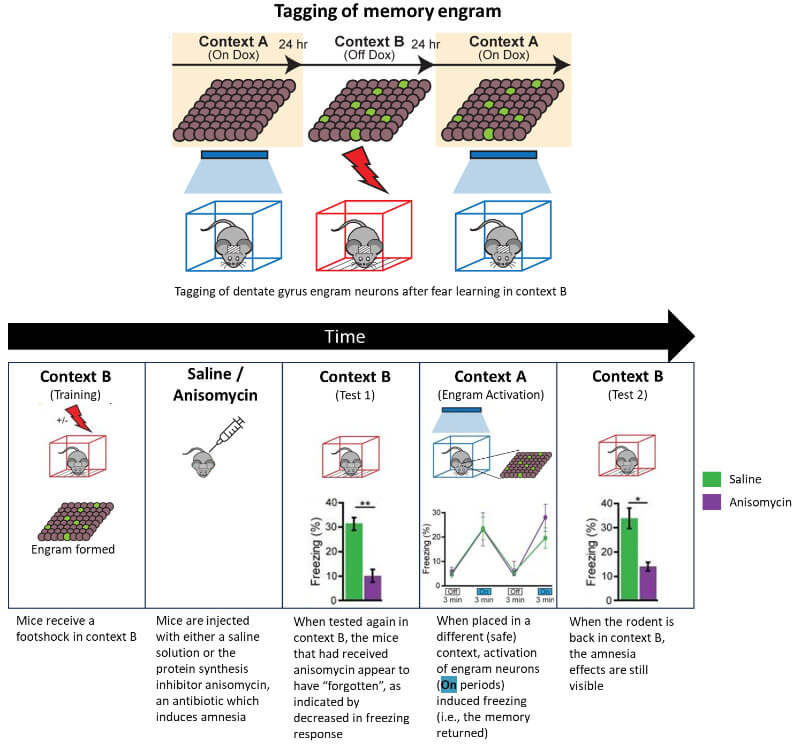

On the other hand, if engrams are simply temporarily inaccessible, they will still exist, but cannot be retrieved by natural retrieval cues. These inaccessible engrams are called silent engrams.

For instance, one study showed that administering a drug that inhibits protein synthesis right after fear learning, disrupted the freezing response in mice tested 1 day later. However, the fear memory returned if engram neurons that had been tagged during fear conditioning were reactivated with optogenetics (see figure above).

This research has natural and important clinical implications in the understanding of memory disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease. The most pressing question is: are engrams in these memory ailments forever lost, or are they simply inaccessible in the sense they cannot be re-activated by natural means?

The jury is still out there.

OK, I’ll tackle To the Moon asking a series of questions that will hopefully lead to a logical conclusion at the end of the article.

Short answer: they cannot.

Dr. Rosalene and Dr. Watts are no genies. What happens is that they use their patients’ own desires (unconscious or otherwise) to make up an alternate life story in their patients’ minds.

For that, they make use of a machine that generates a new mental life of the patient, where the desire dictates the patient’s behaviour. That life is transferred to the actual patient, so that all memories are replaced with the artificial memories generated by the machine.

If you have read the section on engrams above, this shouldn’t sound too outlandish.

After all, even though engram research at the neuronal level has only been applied to animals so far, it is not a stretch to think that one day we will possess the technology to alter memories in humans as well.

Presumably, the machine that Dr. Rosalene and Dr. Watts use to create/erase memories in their patients does pretty much the same thing as what scientists have done to the rodents. That is, the machine might be looking for engrams (the physical substrate of memories in the brain), and once it detects the correct engrams, it proceeds decoding them into images that Rosalene and Watts can actually visualise.

When they transfer wishes to their patients, they are creating artificial memories, just as scientists have been able to do with rodents.

Similarly, deleting memories can be achieved by inhibiting the engram neurons of the to-be-deleted experience.

So, I see the part where River’s memories are deleted from John’s memory as simply probing any events that contain River’s engram, essentially removing her from those events.

John’s last wish was to go to the Moon. Despite not knowing the reasons for such a wish, the two scientists attempt to implant this wish into John’s earliest memories.

When the scientists try to access one of Johnny’s childhood memories, they hit a dead end. Johnny’s earliest memories are distorted and incomplete. Rosalene concludes that this early memory isn’t linking with the other memories for construction.

They thought it was a glitch, so decide to implant the wish to go the Moon on the earliest memory they could access. However, when they did that, they realised Johnny showed no desire whatsoever to go the Moon. In fact, his memories remained exactly the same. No matter how much Rosalene and Watts tried, the implantation of the desire to go to the Moon simply would not have any effect.

At some point, Rosalene cogitates:

“A secondary condition for the desire was changed in the process. Only then, would the same desire produce two different outcomes at two different points in time. […] If there’s anything that could’ve caused the core to change, she [River] would be the top suspect.”

So, Rosalene reasons that something more potent is overwriting the transferred wish and that River is probably the reason that the desire has changed.

It all boils down to what happened during those early years of Johnny’s life that the scientists cannot access.

Remember, Johnny had been given beta-blockers, which disrupted his very early memories.

Luckily, Watts managed to get hold of the “reconfiguration frequencies” that would allow them to get past the blockers and access those early memories.

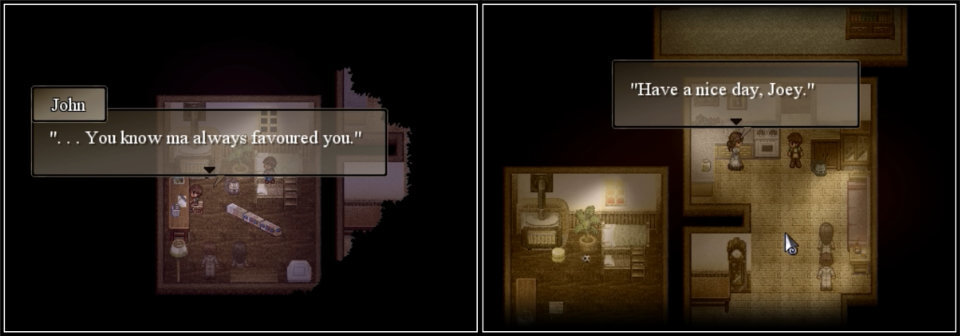

When they are finally able to break the barrier formed by the beta-blockers they come across a memory in which Johnny had a twin brother called Joey. Joey is accidentally killed by their mother, leaving her extremely depressed.

To quell the anguish of losing her preferred son, she gives Johnny beta-blockers, which has the effect of erasing Johnny’s memories up to the time of the accident. There is an interesting parallel with research on mice here. As reviewed above, some research has shown that admistering a protein synthesis inhibitor called anisomycin induces memory loss shortly after fear learning training.

Now, the mother’s intention with administering the beta-blockers to Johnny has been a topic of much debate.

Johnny’s mother had a clear preference for Joey – this is very obvious during a conversation between Johnny and Joey in the bedroom. By erasing Johnny’s memories with the beta-blockers, Johnny’s mother could pretend that Joey hadn’t died, since Johnny was his twin brother. At some point, she started calling Johnny, Joey.

Terrible, I know. But it is corroborated by the conversation between Rosalene and Watts:

Watts: “… What about their [Johnny’s and Joey’s] mother?”

Rosalene: “I don’t think she took the beta-blockers. She seems to have gone a little cuckoo. At least, I don’t really think she called Johnny ‘Joey’ as a nickname.”

Watts: “But if she then takes Johnny for Joey, what about Johnny himself?

One of the critical memories that was erased in the process is the memory of a carnival, where Johny meets River for the first time.

Rosalene and Watts witness this encounter. At some point, Johnny promises River that if they ever get separated, they will “regroup” on the Moon.

Sadly, a few days after the carnival, Johnny’s mother kills Joey by accident, and gives beta-blockers to Johnny to prevent any recollection of this tragic event. Unfortunately, the beta blockers erase all memories from his childhood up to the point of the accident, including the encounter with River a few days earlier.

So, when Johnny meets River at school, he has genuinely no memory of ever having met her, and thinks this is the first time they are actually meeting.

Clearly, River wants Johnny to know that they had previously met. She is seen obsessively crafting paper bunnies. Remember, at the fair, River and Johnny played a game where they try to find a constellation in the shape of an Easter Bunny.

They notice a cluster of stars forming the ears and legs of the bunny, with the moon forming its big belly.

So the paper bunnies River leaves behind in the house are meant to be hints to jolt Johnny’s memory of the encounter at the fair. One particular bunny appears particularly significant to River: the bunny with a yellow body, and blue everywhere else. This bunny is a representation of what they saw together as kids, the yellow belly being the moon, and the blue body being the sky.

Nevertheless, it still seems rather odd that River would not say anything at all, even when it started to hurt their marriage, and making both miserable.

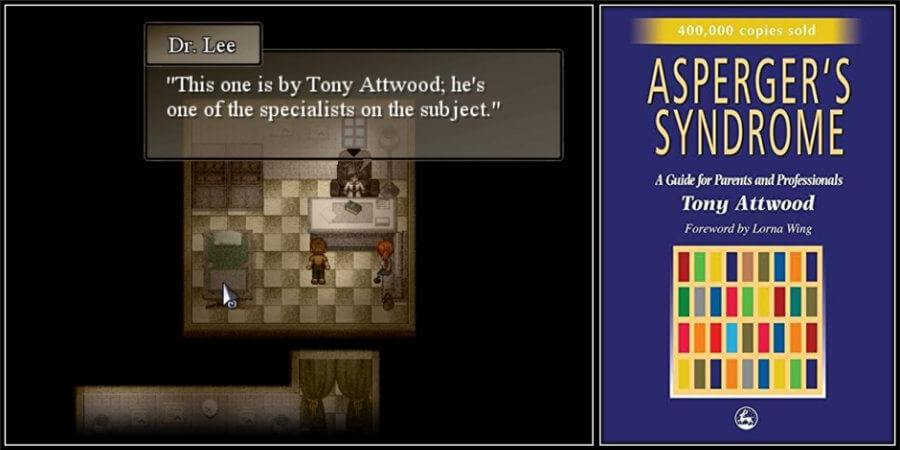

The explanation seems to be that River may have Asperger’s syndrome.

When River and Johnny visit the doctor, River asks the doctor if he has any books about her condition. The doctor gives River a book written by Tony Attwood, and says he is a specialist on the subject.

Well, Tony Attwood is an actual British psychologist with a research focus on Asperger’s syndrome and has written many important books about the disorder (see figure above).

Asperger’s syndrome falls under the broad umbrella of autism spectrum disorders. Some of the most common symptoms include difficulties with social interactions, and problems with communication, language and thinking.

River was in poor health during their later weeks of their marriage. When River was bedridden, Johnny was planning to sell the house to cover the medical bills and for River to be operated. Thus, it is implied that she also had a terminal disease, maybe cancer.

Now, more relevant to River’s autistic condition, she refused medical treatment because she wished John to keep the house, particularly the lighthouse (that she calls Anya) so he can tender to it when she dies.

This fascination with lighthouses is explained during River’s and John’s first encounter at the fair.

When River was a child, she had the belief that stars were billions of lighthouses stuck on the sky. They could all see each other and wanted to talk to one another, but they could not, since they were too far apart to be able to communicate. So the lighthouses could only use their lights so that the others, and River, knew they were there. River tells John that the reason the lighthouses were also shining at her was because she wanted to befriend a lighthouse one day.

Note the focus on communication, which may represent River’s attempt at (and long for) social interactions. I believe this partly explains why River never really directly confronted Johnny about their first encounter at the fair – she simply struggled to express and communicate her feelings and frustrations.

Rosalene concludes that the only way they can “send” John to the Moon is if he’s sufficiently motivated to go and that means removing River from John’s early memories. Remember, none of the memory implantations in his early childhood were a motivation enough to alter the course of John’s history.

When Watts protests, Rosalene reminds him that they are legally bound by the contract to fulfill John’s wish to go to the Moon, which they only can by erasing the memories of River.

But you see Watts argument, right? The only reason John wants to go to the Moon is because of River. If they remove River from the picture, there is no point of John going to the Moon. To Watts, John would be happier in a life where he had met River and not go to the Moon, so why removing her?

The reason why Rosalene thought River needed to be out of the picture has puzzled me for days…

But I think I get now what she was trying to do.

Let me explain.

Johnny promised River he would meet her on the Moon if they ever got separated, which happens after River dies.

Now, when they try to transfer a desire for Johnny to go to the Moon, it doesn’t work.

But why should it work anyway?

After all, Johnny will not want to go to the Moon because River is in his life, and Johnny prefers to be with River than not to be with her.

However, after River dies, the memory of their initial encounter at the fair still lingers in his subconscious.

And it is River’ death that triggers the retrieval of this unconscious promise to regroup in the moon, causing John’s inexplicable wish to go the Moon.

So, Rosalene has the idea to “remove” River from his memories.

Now, from here on, there are two versions, both of which could be true, and it relies on whether or not memories of River are completely erased.

Version 1: The memory of meeting River at the fair is preserved

With this version, we are assuming Rosalene removed the memories of River after the encounter at the fair.

So, the encounter at the fair still took place.

After the fair, Johnny and River never meet again, so the promise he had made to her about reuniting in the Moon in case they never saw each other again is unconsciously stored in his brain.

Thus, by removing River from Johnny’s memories (but keeping their encounter at the fair), Rosalene is using River’s absence to trigger Johnny’s unconscious desire to go to the Moon and keep his promise to River.

Version 2: All memories of River are deleted from John’s brain

Here we assume that Rosalene erased every single memory trace of River from John’s brain, including their meeting at the fair.

Now, I don’t think there is any evidence to support this version, since the memories that have been erased are shown in temporal order, starting from when Johnny meets River in the school’s staircase, then the cinema date, the horse-ride, the marriage proposal at the lighthouse and so on.

Of course you could argue that if River and Johnny’s encounter at the fair wasn’t deleted then Johnny would have somehow remembered meeting River. So, the fact that he did not recognise River when they met at NASA is evidence that no trace of River was present in John’s brain whatsoever.

However, surely River would have looked very different from when she was 6 years old. Furthermore, remember that River never told Johnny her name during their encounter at the fair, so Johnny wouldn’t be able to associate the name River with the NASA’s newly recruit.

So, in my view, the promise he had made to River wasn’t deleted and that was what Rosalene decided to use as trigger to arouse Johnny’s desire to want to go to the Moon.

One thing the game gets often criticised is Rosalene’s logic of getting rid of River, hoping River would magically return and be with Johnny.

Most people discard this as a very fortuitous coincidence. After all, River wasn’t even in the same school as Johnny so she wouldn’t have been influenced by his decision to go to the Moon.

So, not only River would need to want to become an astronaut, would need to have a desire to go to the Moon, would need to apply at about the same time as Johnny did, would need to be able to get into NASA, and would need to be assigned to Johnny’s team.

That’s a lot of woulds!!! What are the chances of that happening?!?

Well, here is where people get it wrong, in my opinion.

We are assuming we cannot control River’s decisions, since it’s up to her what she does with her life.

That’s true.

However, River in Johnny’s mind isn’t the real River. In fact, nothing in Johnny’s mind is real. Everything has been fabricated by the machine. To be more precise, the machine generates Johnny’s new life based on Johnny’s desire and consequent response to that desire.

This is key in understanding Rosalene’s hunch. Johnny’s subconscious has still registered the encounter with River at the fair, and the promise he had made in case he “gets lost”. It is Johnny’s unconscious that is driving his desire to meet River on the Moon, and the machine works towards that goal. River is introduced in Johnny’s memories exactly where she needs to be – at NASA, training to become an astronaut for a Moon expedition, where she will be able to be with Johnny.

So, in my opinion, Rosalene’s hunch was very much spot-on!

Comatose patient, Johnny, had an inexplicable wish to go to the Moon, and hire Dr Rosalene and Dr. Watts to use their special machine to make him believe he did.

As the scientists later learn, Johnny had met his later-to-be-wife River at a fair when they were children, where he promised her to regroup on the Moon in case they ever got separated. After Johnny’s brother is tragically killed, Johnny is given beta-blockers that have the effect of erasing most of his memories, including the encounter with River.

River and Johnny eventually marry each other. However, River, who appears to possess a form of autism, never mentions their first encounter as children, and is upset that Johnny does not remember it.

The scientists realise that transferring the wish to go the Moon will not work because Johnny doesn’t want to be apart from River. So, Rosalene has the clever idea of removing River from Johnny’s memory, so that Johnny’s unconscious promise he made to River (that they would regroup on the Moon) could drive his desire to become an astronaut and want to visit the Moon.

In this alternate (mental) life, Johnny becomes an astronaut at NASA, and is later introduced to fellow-astronaut River, who is a product of Johnny’s desire to meet with River on the Moon.

While I acknowledge the poignant story-line and interesting script, I found that, as a video game, To the Moon lacks in many critical aspects. The poor game mechanics, lack of interesting puzzles and laconic dialogues certainly took my enthusiasm away from the game. Furthermore, the lack of emotional expressions and absent voice acting in a game that is supposed to evoke deep emotions makes me wonder if perhaps a different medium would have been more suited.

To the Moon inadvertently touches on one of the most fundamental problems in philosophy of mind.

Can it be that our consciousness is solely the product of a bunch of engrams with a physical location in the brain? Is it possible that experience, thoughts and desires are simply the activation of a bunch of these engrams? Can it really be that easy to manipulate and modify one’s memories by simply activating/inhibiting these engrams? That is, at least, the premise of To the Moon, and what gives Rosalene and Watts a paycheck.

This is surely a very provocative thought, but also an uncomfortable one. After all, messing up with stored content in the brain has stopped being purely the work of fantasy and science fiction. Manipulating and creating artificial memories in the lab is now child’s play, at least in rodents.

But perhaps it is only a question of time until the same could be done in humans.

Yikes! I don’t know if I should be fascinated or terrified…

Maybe both?

Yeah, definitely both!

See you in the next article!

Journal articles

Josselyn S.A., et al. (2015) Finding the engram.

Josselyn S.A. & Tonegawa, S. (2020) Memory engrams: Recalling the past and imagining the future.

Ramirez et al. (2013). Creating a False Memory in the Hippocampus.

Vetere et al. (2019). Memory formation in the absence of experience.

Ryan, T.J. et al. (2015). Memory. Engram cells retain memory under retrograde amnesia.

YouTube

About optogenetics:

Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)

About engram research:

Lovely article 🙂

Hi Ewan,

Thank you very much for your comment – I’m happy you enjoyed the article! 🤗