This post is part of a larger deep dive

Curious about the role of the WWII atomic bombings in Raphaelesque Head Exploding? Check out Raphaelesque Head Exploding explained!

Or read the full Raphaelesque Head Exploding article!

This post is part of a larger deep dive

Curious about the role of the WWII atomic bombings in Raphaelesque Head Exploding? Check out Raphaelesque Head Exploding explained!

Or read the full Raphaelesque Head Exploding article!

One of the things I admired about Dalí as an artist was his deep interest in the sciences. Copious letters survive as evidence of how Dalí kept close correspondence with mathematicians, physicists, biologists and neurologists.

His fascination with science led him to the works of Albert Einstein, Stephen Hawking and many others. He was so fascinated with science that even subscribed to scientific journals in order to keep up with the most recent scientific advances.

One particular field that was to become Dalí’s obsession was that of nuclear physics. After Germany invaded France during the beginning of the second World War, Dalí moved to the USA with his family.

The atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945 made an indelible mark on Dalí. Speaking to his friend André Parinaud, Dalí said:

“The atomic explosion of 6 August 1945 seismically struck me. Since that time, the atom has become my favourite subject of reflection. Many of the landscapes painted over this period express the great fear I felt at the news of that explosion. I was applying my paranoiac-critical method to the exploration of that world. I want to see and understand the power and hidden laws of things so as to gain control over them. In order to penetrate into the marrow of reality I have the genial intuition of having an extraordinary weapon available to me – mysticism, the deep intuition of what is, an immediate communion with the whole, absolute vision through the grace of truth, by divine grace”.

Salvador Dalí

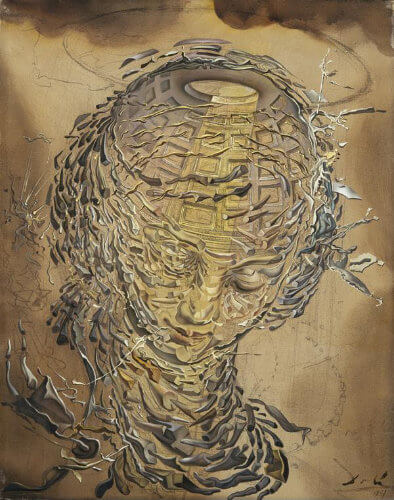

With further developments in nuclear fusion, Dalí developed a unique style that he termed “nuclear mysticism”, which combined elements of diverse fields such as classical physics, Catholic mysticism and classicism. It was during this period that the Raphaelesque Head Exploding was produced.

And I believe the painting is a perfect illustration of that combination.

Let’s see what I mean by that.

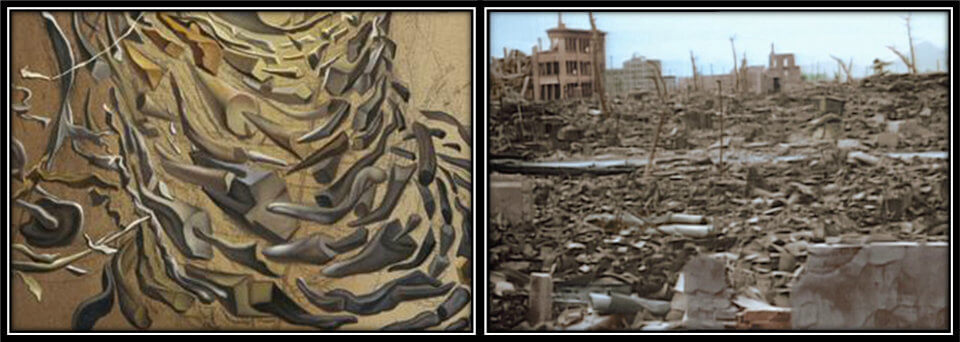

If you have read the section on The making of a bomb you will have an idea of just how destructive the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki were.

The fragments on the painting could represent the disintegration of everything that happens to be in the path of such an atomic explosion.

Alternatively, they have also been interpreted as swirling sub-atomic particles, which, as explained above, are the constituents of the atoms that make up all matter.

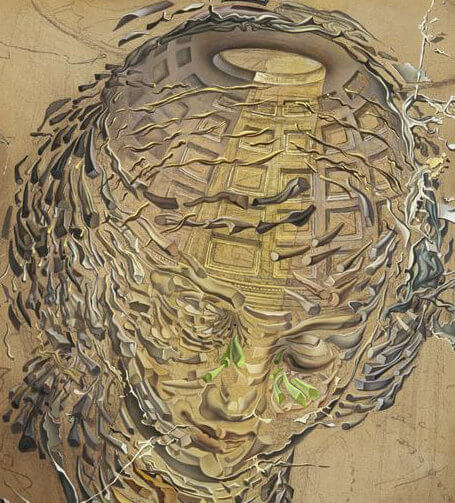

Another interesting connection to the effects of nuclear physics is the focus of light emanating from a hole at the top of the head (see figure above).

In physics, fission leads to the release of heat, which is converted into light. Indeed, many survivors of the Hiroshima bombing reported having seen a very bright light before any explosion sounds were heard. People looking in the direction of the explosion would experience flash-blindness.

Thus, it is not a stretch to think that the light shining through the head of the subject in Dali’s painting may be a representation of the blinding light that was emitted after the atomic explosion.

Both the clouds and halo are likely representations of the mushroom cloud seen after the nuclear explosions of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombing (see figure above).

In fact, note how the light seems to originate from this “mushroom cloud” above the head.

The identity of the face that appears in the painting is undoubtedly the face of Madonna, the Virgin.

In fact, this head is supposed to be a Raphaesque’s head (meaning a head based on the work of Raphael). The similarities between the head in Dalí’s painting and some of Raphael’s work depicting the Madonna are indeed staggering (see figure above).

It is a peculiar combination, classical physics and Christian iconography, but that was Dalí my friends.

Dalí is cleverly using the image of a Madonna – a prominent Christian symbol for purity – as a sharp contrast to the callous and wicked use of nuclear weapons.

And the effect is truly powerful.

Here you have an image of heavenly perfection being desecrated by human violence, aggressiveness and immorality. Making up the face with fragments akin to those resulting from a nuclear explosion confronts the viewer with two completely opposing ideas, leading to a certain confusion: we cannot really call the face beautiful, but we cannot call it ugly either.

Another interesting detail is that if you pay close attention to the area around the eyes you might just make out tears running down the face (I have highlighted some of them in a yellowish tone in the the figure above).

So, once again, Dalí is playing with contrasts. What you might believe to be a serene and content facial expression, now has the appearance of showing desperation and sorrow.

Above the head we see what appears to be a halo, further implicating Christian symbolism in this painting. A halo is often depicted in Christian art as a circle formed by rays of light. A Catholic interpretation of the halo could be that it represents perfection and divinity.

Again, Dalí is playing with contrasts here. The halo, symbol of perfection and divinity, stands in stark contrast to the horrible destruction caused by nuclear weapons, which, in Dalí’s painting, is represented by the condensation ring (very briefly, the shockwave caused by the explosion has an area of high and low pressure. In areas of low pressure, there is a drop in air temperature below its dew point. The moisture in the air condenses and forms water droplets, which is what makes up the “ring” we see in the photographs of nuclear explosions; see figure above).

Dalí also added a peculiar wheelbarrow at the bottom left corner of the painting, which blends itself naturally to the remaining fragments of the head.

Dalí purportedly painted the wheelbarrow after becoming enamoured with a painting called “The Angelus” by French Realist artist Jean Francois Millet (see figure above).

What is interesting about this fact is that Millet’s painting shows two peasants saying a Catholic prayer called “The Angelus”, signaling the end of a day’s work.

However, for some reason, Dalí became convinced that the scene did not depict a prayer ritual, but rather the mourning of a lost child. Astonishingly, the Louvre did detect an outline of a child’s coffin just under the basket of potatoes when it later X-rayed the painting!

Millet died several years before Dalí’s birth, so how Dalí came to this insight, no one really knows.

But we could speculate that the addition of the wheelbarrow in Dalís work is not only a tribute to Millet’s influence, but also a representation of a more poignant reality: the mourning of the dead from the atomic bombings.

The influence of classicism is also seen in Raphaesque Head Exploding with the depiction of the interior of the The Pantheon of Rome.

The Pantheon of Rome was originally built by Roman general and architect Agrippa sometime between 25-27 BC, in commemoration of the Battle of Actium, the infamous naval battle that saw the defeat of Mark Antony and Cleopatra. Patheon derives from the Greek word πάνθειος (pántheios), which means “of all gods”, so it is likely that the original Pantheon was a temple dedicated to the twelve Roman Gods.

After Agrippa’s Pantheon burned down in a fire in AD 80, Emperor Hadrian built his own version of the Pantheon on the same site around between 113-125 AD, which is the current building that survives to this day.

In the middle ages, the Pantheon was converted to a Christian church and renamed Sancta Maria ad Martyres (St. Mary and the Martyrs).

The Pantheon’s dome contains five rings of 28 rectangular coffers (square-shaped sunken panels) on its ceiling. The interior of the head is covered with coffered panels, just as the interior of the Pantheon (see figure above).

An oculus, the large uncovered opening on the ceiling of the Pantheon, provides the main source of natural light, and, in sunny days, you can see light beams entering the opening, illuminating the interior of the building. Likewise, the beam of light entering the opening at the top of the head simulates the effect of the light beam entering the oculus of the Pantheon.

The Pantheon served as a great inspiration to Raphael, who requested to be buried there. Given Dalí’s fondness for Raphael’s works, I find these associations particularly relevant when analysing Dalí’s work.

Indeed, we can find at least three associations between Raphael and Dalí’s painting: the title, the Madonna, and the Pantheon. Perhaps, in a way, Raphaelesque Head Exploding was Dalí’s dedication to Raphael.

The Pantheon’s dome may have been built to resemble the heavens. The oculus was designed to function as a sundial, but also likely intended to represent the connection between mortal beings and the gods (the Pantheon was originally a pagan temple).

This suggests that the dome and the oculus in the painting are meant to represent something transcendental, godly or divine. What is Dalí trying to tell us by making this connection?

As Dalí became fascinated with nuclear physics, he took a special affinity with the idea of the atom making up everything in nature, which led him to attempt at unifying science and religion under the self-conceived notion of “Nuclear Mysticism”. Perhaps Dalí is mischievously insinuating that nuclear physics experimentation is, in a way, like playing God. In other words, he may have viewed the immense destructive power of nuclear weapons and the cataclysm it causes in a way that would rival the powers of the gods.

I should conclude with the note that even though Dalí was utterly shocked by the bombings on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, he also saw scientific progress (including the advances in nuclear physics) as an inevitable reality that the world of art needed to accommodate if it were to adapt the modern world.

One can only imagine the kind moral turmoil going inside Dalí’s head, hoping for unending scientific progress but terrified of its consequences.

Raphaelesque Head Exploding must be one of Dalí’s most enigmatic works.

The association to Raphael’s Madonna is very obvious but there is undoubtedly an inexplicable feeling of unease when viewing Dalí’s painting that we certainly don’t find in Renaissance works.

The central head is both beautiful and hideous, both pleasant and unpleasant, both safe and dangerous… Dalí achieved this effect by forcing viewers to contrast images of perfection and magnificence (Madonna’s gentle expression, the halo, the Pantheon) against images of defilement and desecration associated with destruction, war and pain (e.g., fragments composing the face, tears, the mushroom cloud, the condensation ring).

He also suffused the painting with symbolism. The bright light that illuminates the face has its origins in the halo and clouds above the head. Perhaps a representation of the blinding light resulting from a nuclear explosion? A wheelbarrow meshes with the head fragments. Perhaps a representation of mourning the deceased? The coffered panels of the Pantheon dome covering the interior of the head. Perhaps a representation of the almost god-like powers of manipulating the very fundamental structures of matter?

A Dalí painting, that’s for sure!

In retrospective, perhaps Huettel and colleagues chose Dalí’s painting for their fMRI book simply because, visually, it sort of appears that the light is illuminating the inside of the head which, figuratively speaking, is what fMRI is used for (i.e., it allows researchers to “visualise” the inner workings of the brain).

Whatever the reason, it was enough to grab my attention, and I can now rejoice that I have finally analysed one of my favourite paintings.

I can only thank the authors for that! 😊

See you in the next article!

Leave a comment

Add Your Recommendations

Popular Tags