This post is part of a larger deep dive

Curious about the role of Freud's theory of the psyche in The Anthropomorphic Cabinet? Check out The Anthropomorphic Cabinet Explained!

Or read the full The Anthropomorphic Cabinet article!

This post is part of a larger deep dive

Curious about the role of Freud's theory of the psyche in The Anthropomorphic Cabinet? Check out The Anthropomorphic Cabinet Explained!

Or read the full The Anthropomorphic Cabinet article!

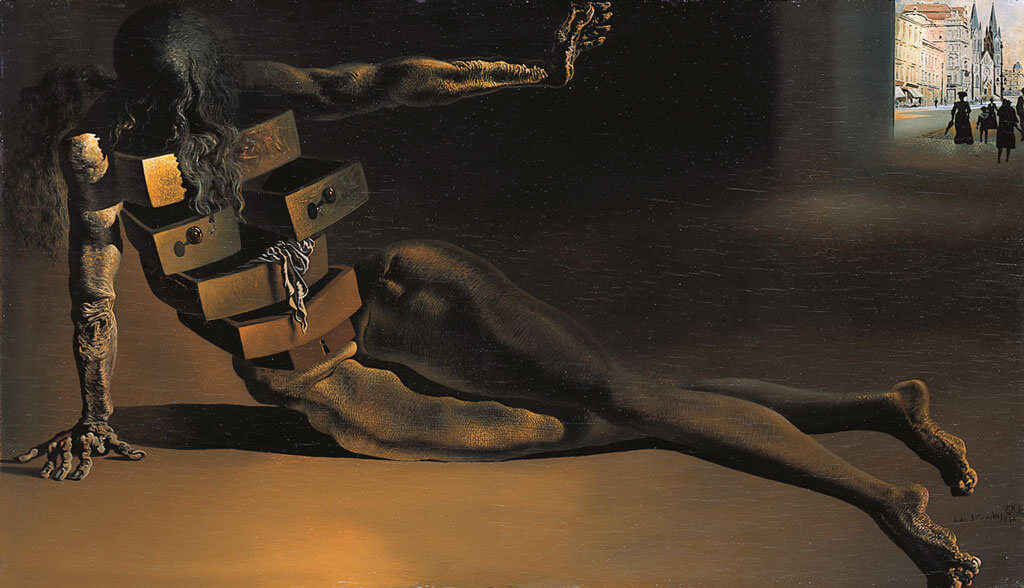

Let’s first begin with a dissection of the title of the painting.

Anthropomorphic means treating particular objects as if they had human characteristics. For example, Babar the Elephant is an anthropomorphism, because Babar has human traits (he talks, dances, and drinks tea with his fellow elephants).

A cabinet is a type of furniture with drawers and/or shelves.

So the name of the painting implies a cabinet with human qualities. Let’s rephrase this to really make a point here: the “woman” portrayed in the painting is not really a woman with drawers on her torso; it’s a cabinet to which Dali added female features.

We have just started out our journey and already made quite a progress in our analysis of this artwork: the primary element of the painting is an object, not a person.

The cabinet-woman could thus be seen as a representation of the unconscious mind, a cabinet that stashes all our primitive urges and desires.

Dali once said:

“The only difference between immortal Greece and contemporary times is Sigmund Freud, who discovered that the human body, purely platonic in the Greek epoch, is nowadays full of secret drawers that only psychoanalysis is capable to open.”

If you read the section on Freud and the unconscious mind, you should be able to understand what Dali meant with this.

The drawers represent niches of unconscious and repressed material that can only be revealed by proper psychoanalysis.

But why did Dali use drawers to symbolise the unconscious mind?

Well, if you think about the functionality of the drawer, it becomes clear that just as you can take clothes out, you can also put them in.

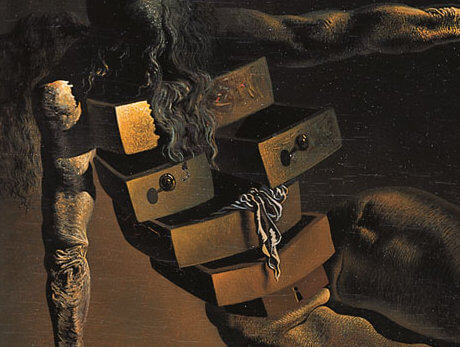

The drawer knobs are clear allusions to the nipples, whereas the key hole (you guessed it) represents the vagina.

With these two details, Dali is expressing one of the central theses in Freud’s psychoanalytical theory os the psyche: the human nature predominantly obeys to unconscious sexual impulses.

Take the piece of clothing sticking out from one of the drawers, which appears to be some kind of woman’s lingerie. Well, lingerie is a very personal feminine kind of garment, isn’t it? You do not walk around in underwear for a reason, and only people with whom you have intimacy get to see it.

In fact, the disposition of the clothes in the drawers could take three meanings:

1) if the drawers are opened with clothes sticking out, it could represent the attempt at bringing a person’s own repressed thoughts/memories/wishes to the surface.

2) if the clothes are kept inside closed drawers, it could indicate buried thoughts/memories/wishes in the depths of the unconscious.

3) if the open drawers contain no clothes, it could indicate successful integration of those memories into the self.

In this particular painting, the drawers are opened, most of them empty but the drawer with the lingerie. This could indicate attempts at making unconscious content conscious.

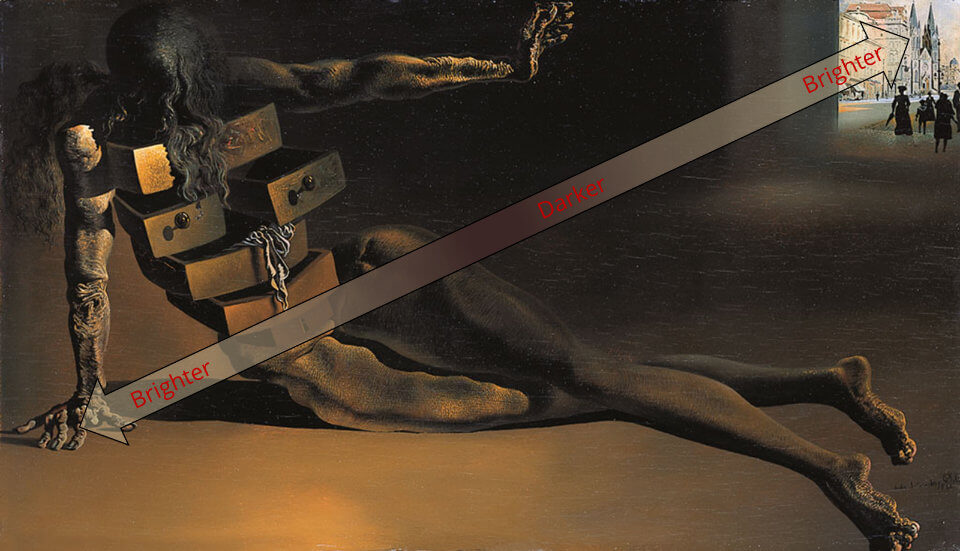

Another interesting composition aspect of the “The Anthropomorphic Cabinet” is the lighting. Your gaze is immediately directed to one of the brightest areas of the painting: the cabinet-woman. A bright light falls on the reclining and slightly disfigured female body, which appears to be in the process of disintegration. So, the light shining over the body could symbolise the shining over repressed material in order to bring it to light, to consciousness.

However, as with most unconscious repressed material, this experience might be a painful and shameful one. The despair look in the woman’s figure suggests shame, guilt and/or embarassment of some kind, and, as discussed above, the lingerie has a likely sexual connotation. This is related to Freud’s idea that most unconscious material are sexual (unconscious) wishes that are simply too disturbing to the mind. Note the head hanging occluding the face, as if to hide the shame and the strecthed arm as if begging for the observers (top right) to leave her be.

Indeed, facing repressed material can be very difficult, but it is necessary, since unresolved repressions often appear as unwelcoming symptoms. It is the job of the psychoanalyst to help the patient cope with these internal conflicts and guide him/her on the journey to resolve those conflicts.

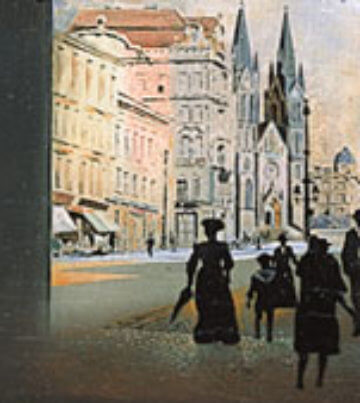

At the top right corner of the painting, we can spot the sillouette of several human figures standing at the boundary between the inside and the outside world – the Preconscious.

The sillouetes stand out, which is perhaps an indication that they are significant elements in the narrative. But what might they represent?

As mentioned above, the final repressed memory (represented symbolically by the hanging lingerie) is crying out to be made conscious.

We could speculate that the individual holding this repressed memory needs to come to terms with these figures – perhaps acquaintaces or people that were integral to the formation of this repression.

Once the repressed event has been successfully integrated, these sillouetes will finally step out into the light (into consciousness; which is the brightest area of the painting), as the internal conflicts have been resolved.

Alternatively, the sillouetes could represent the internal censorship. According to Freud’s first topic, there are two censors: one between the Unconscious and Preconscious, and another between the Preconscious and Conscious.

The censor ultimately decides which material should reach consciousness and which material should remain buried in the Unconscious.

So perhaps these figures, who appear to be patiently observing whatever is going on inside the room, are simply judges of memories to come. If so, what outcome for the last repression do you think Dalí had in mind?

Freud’s tripartite theory of the human psyche (Consious, Preconscious, Unconscious) was a turning point in the history of Psychology, and the division between conscious and unconscious systems was one of Freud’s greatest contributions.

The Anthropomorphic Cabinet beautifully illustrates this divide, and Dalí did it with mastery. I find it interesting that Dalí chose not to overwhelm the viewer with colour and juxtaposition of objects as some other surrealistic art (even some of Dali’s other works).

Still, I cannot help but feel the despair in the narrative of the painting, as if something mysterious and disquieting was trying to reach out… Is there a better visual description of Freud’s idea of the Unconscious than that?

This painting reveals not only how technically gifted Dali was, but also his acumen in turning Freud’s abstract and complex psychoanalitical ideas into actual shape with a handful of compositional elements.

Freud must have been impressed!

Despite your feelings towards Freudian psychoanalysis there is little doubt that Freud was pioneer in bringing the unconscious to the fore, at a time when it was largely ignored (although to be fair, some philosophers, such as Nietzsche, had already proposed the existence of an unconscious mind). Today, science has confirmed the existence of an unconscious mind, as evidenced, for example, in various forms of implicit cognition.

Dalí, an avid reader of Freud’s works, likely saw the potential of Freud’s grand idea as a novel avenue for surrealism, and was quick to incorporate it in his own compositions.

At times, I daydream about that 1938 encounter between Freud and Dalí. Really, how awesome it would have been to witness two of the most illustrious personalities of that time exchanging thoughts and ideas about the unconscious mind.

See you in the next article!

Books

Martí, Marc Pepiol. Freud – Un viaje a las profundidades del yo. Shackleton books.

Néret, Gilles. Dalí. Taschen.

Leave a comment

Add Your Recommendations

Popular Tags