This post is part of a larger deep dive

Curious about the role of free-association and the Activation-Synthesis Theory in The Elephant Celebes? Check out The Elephant Celebes Explained!

Or read the full The Elephant Celebes article!

This post is part of a larger deep dive

Curious about the role of free-association and the Activation-Synthesis Theory in The Elephant Celebes? Check out The Elephant Celebes Explained!

Or read the full The Elephant Celebes article!

During the early years of psychoanalysis, psychoanalysts were in search of a therapy that could potentially treat many of the known psychological ailments at the time.

One of these therapies was hypnosis. Put simply, hypnosis consisted of ensuring the patient remained silent and focused, while the psychoanalyst whispered words and used gentle movements to soothe any symptoms that caused pain in the patient.

Now, hypnosis had many setbacks.

First, it wasn’t really generalisable. In fact, its effectiveness was very much restricted to the treatment of neurosis, which was what Freud devoted most of his time with.

Second, not everyone was equally suggestible, so hypnosis would not work for everyone.

Third, even if the patient could be hypnotised, the suggestions simply did not stick. For example, the therapist might have been able to calm down a patient suffering from anxiety using hypnosis in his office, but an emotional trigger could revert the patient back to the pre-hypnosis anxious state.

Freud was aware of the limitations of hypnosis, and was determined to find a more suitable alternative.

His idea was to find a technique with which he could access patients’ mental conflicts in a more direct and stable way.

By mostly trial-and-error, Freud came up with the free-association technique.

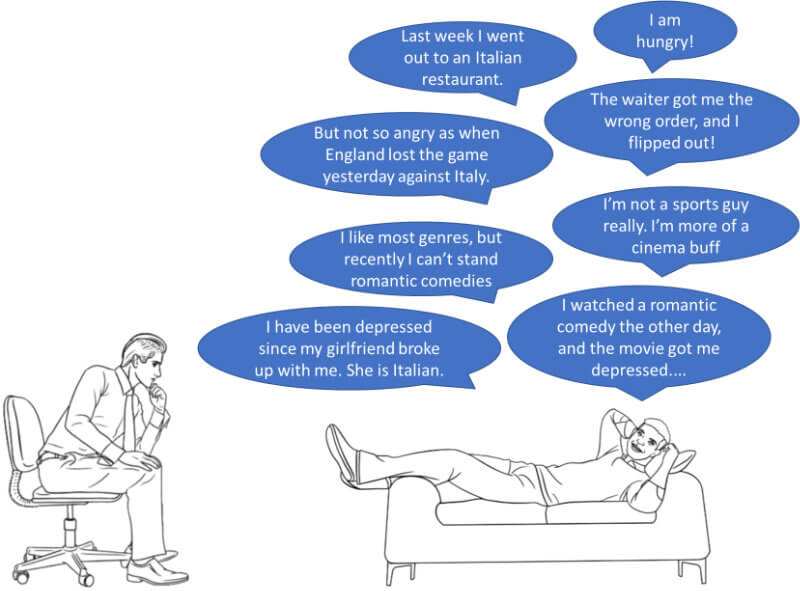

The free-association technique consisted of asking the patient to narrate the initial experiences that the patient could immediately associate with the appearance of the symptoms.

Next, the therapist would ask the patient to say whatever spontaneous thoughts came into his/her head.

Importantly, the patients were told they shouldn’t think about or rationalise the thoughts. They should simply say out loud whatever images or words appeared in their minds.

Little by little, a trained psychoanalyst would be able to piece together these seemingly random thoughts into a (more or less) coherent past history of the patient.

Freud considered that every mental process must obey reason. So, if the patient tried to avoid a particular association (e.g., she corrected herself), it probably meant that this was the result of consciousness trying to prevent disturbing unconscious thoughts from emerging.

As soon as the psychoanalyst became aware of that resistance, he/she would intervene and investigate the reason for avoiding that particular association – for example, by asking further questions regarding that association.

It was the therapist’s task to successfully knock down the barriers of resistance, in order to bring the obscure content to consciousness. Only once this content was consciously exposed, could the patient manage the true wishes, emotions and desires related to the traumatic content.

It should be stressed that Freud subjected himself to the free-association technique he invented. In fact, he was his very first patient, and always reserved an hour or two per day for this activity, until his death.

So, in summary, free-association technique is nothing more than allowing the patient to quickly voice any thoughts, words or images that appear in his mind without deliberation, no matter how incoherent they may appear.

Even though free-association was invented as a means to treat disease, it can be applied more generally as a way to peak into the unconscious mind.

Free-association can also be used on dreams. Instead of directly asking patients what they think their dreams meant, they are encouraged to tell the analyst whatever comes to mind in relation to their dreams, regardless of how embarrassing and unpleasant these thoughts may appear.

To Freud, the free-association technique on dreams was indispensable for unravelling the true meaning of the dream.

But what if dreams have no meaning? What if the contents of your dream are nothing more than the by-product of erratic brain activity occurring during sleep?

In the 70s, late American psychiatrists and dream researchers Dr. John Allan-Hobson and Dr. Robert McCarley of Harvard University put forward a neurobiological theory of dreams called “activation-synthesis hypothesis”.

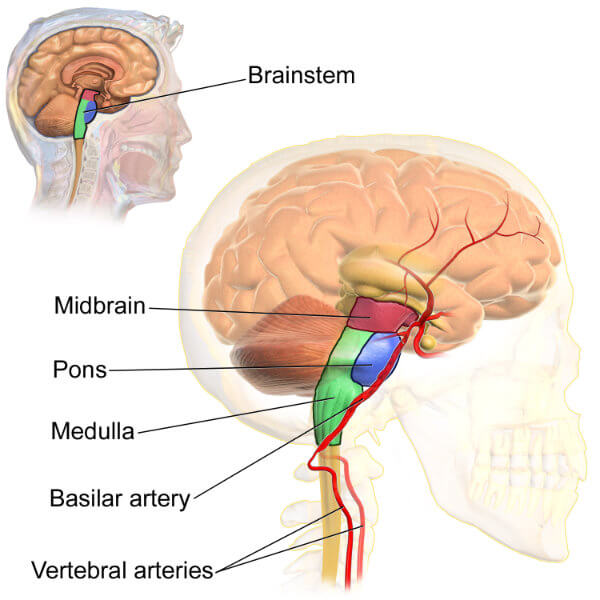

According to this hypothesis, the genesis of a dream takes place in a location called the pontine reticular formation (PRF) situated in a part of the brain stem called the Pons (see figure above).

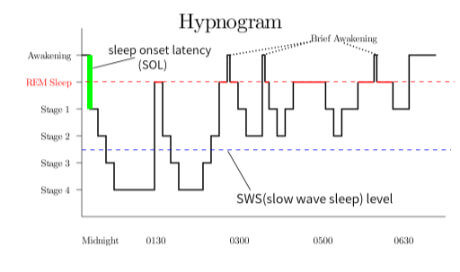

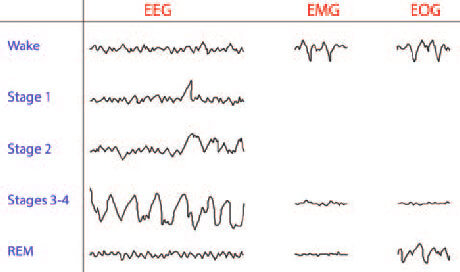

Research has shown that the firing of PRF neurons generates very distinct rapid-eye-movements (REM) while we are sleeping. It just happens that it is in this REM sleep stage when most (but not all) of our dreams take place (see Sleep Stages).

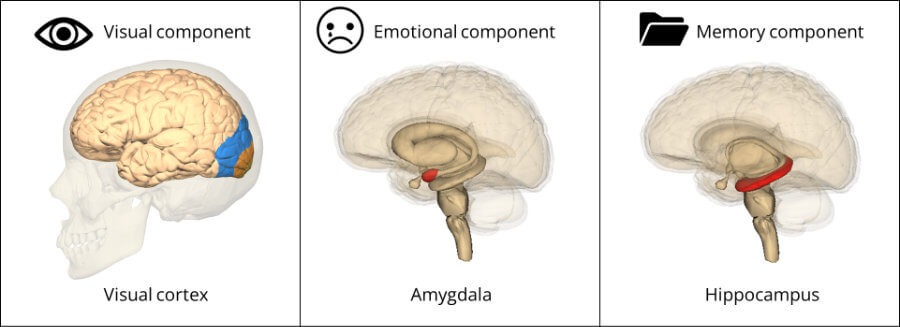

The activation of the PRF propagates to several brain areas of the cerebral cortex.

For example, it stimulates the visual regions (e.g., occipital cortex), explaining why our dreams are so visual.

It also stimulates the limbic system, a set of brain structures that are involved in emotion and memory processing (e.g., amygdala, hippocampus). The involvement of the limbic system during dreaming explains why our dreams can be so emotional-laden and why they often include known events, people and past experiences.

The brain is wired to process information. While we are awake, the brain interprets the information from our senses. For example, if we pick up our baby everything connected to that experienced (the touch, the smell, the baby’s laugh, the baby’s physical appearance, how we are feeling, etc.) is processed (or synthesised) by our brain to form an impression of that moment.

When we are dreaming, however, all the information the brain receives is generated internally (via this spontaneous and largely random firing from the PRF neurons).

Nevertheless, the brain is hard-coded to process that information. In the absence of external stimuli, the brain tries to synthethise the best it can these random signals from every part of the brain into a coherent narrative. Using the words of Hobson and McCarley:

“the forebrain may be making the best of a bad job in producing even partially coherent dream imagery from the relatively noisy signals sent up to it from the brain stem“

So, to recap, the activation part of the “activation-synthesis hypothesis” is really just the (mostly random) neuronal activation within the brain stem. The interpretation of these random signals from the brain stem by the cerebral cortex is the synthesis part of the “activation-synthesis hypothesis”.

This painting from Max Ernst is a masterpiece. Yes, Max used borrowed elements from other paintings but that should not confuse anyone as to what the painting is about. The painting was about how Europe after having experienced the first industrialized war in humanities history should have been doing everything in their power to never revisit such destruction and horror. This he had witnessed first hand as a soldier in WW1 for 4 years. Instead just 3 years after such a horror – Europe began lumbering towards an even more mechanized industrial conflict. Hitler and the other Fascists had after all moved from political rants and grumblings in beer halls in 1921 to a shooting revolution just 2 short years later (Beer Hall Putsch). Therefore Ernst paints the sky as apocalyptic in prediction of the future which he felt in his bones or perhaps subconscious was coming. The confusion of Europe and particularly Wiemar Germany and the decapitated Austrian Hungarian Empire where women were then permitted to have some rights is represented as a nude beheaded manikin leading the lumbering industrial war machine (Celebes).

I found this site looking for an image of the back of the Elephant Celebes for a sketch I am working on for a different composition. Therefore to understand why this painting is as important as Starry Night must be understood from the perspective of WW1 and the defeated Axis nations. Hyper inflation was raging in the ragged economies Axis economies. In 1921 the German currency became so inflated a US dollar was equal to 4,210,500,000,000 marks in 1921. Yes that was trillions of Marks to a single US dollar. Therefore surreal yes but within a very surreal existence for Max and most others at that time.

Hi Leo,

Thank you for your comment and analysis of the painting!

I briefly linked some of the elements of the painting to WWI but, honestly, felt that the more parsimonious explanation of being the product of free-association more likely.

For example, the idea for the mechanical monster appears to have been taken from an anthropological magazine, and it seems unlikely that Ernst based the idea of the elephant from his war experiences (a horse would have been more fitting, for example). More likely, Ernst found the idea of an elephant amusing, either in connection to the German satirical verse, to the elephant-shaped Indonesian island called Celebes, or simply to the shape of the clay corn bin.

Also, Ernst’s interest in Freudian theories, particularly the free-association technique, and their increasing relevance to the surrealists of the time might also indicate Ernst’s work mode. The decapitated nude female and the surgical glove are most likely influences from de Chirico, given the recurrence of these elements in the latter’s works (Ernst was also a great admirer of de Chirico’s paintings).

So, given these points, and a lack of analysis of the work by Ernst himself, I saw The Elephant of Celebes more as an experimental creation in the very early surrealistic movement rather than a homogenous symbolic artwork.

Of course, it’s just my interpretation. As you said, there is the possibility that Ernst’s “random” ideas may have been used within the scaffold of a larger and more meaningful idea, which Ernst remained silent about. It was that scaffold linking these seemingly random elements that I tried to identify in my analysis, but, in the end, I wasn’t convinced I’d found it…

Outstanding

Elephant Celebes

Okay, let’s break down “The Elephant Celebes,” which Ernst cooked up in 1921. Imagine stepping into a dream where nothing makes total sense, but it’s intriguing as heck. In the center, there’s this funky-looking elephant creature, all twisted up and wearing strange stuff. Around it are these mysterious shapes and structures, like something out of a surreal fairy tale.

Many thanks for your review!

Indeed, I agree that the entire painting looks as though we are viewing someone’s macabre dream, full of weird surrealistic elements.

You rated it 4.5 stars, is there any particular aspect of the painting that you consider exceptional?