This post is part of a larger deep dive

Curious about the role of the nature of consciousness and free will in The Talos Principle? Check out The Talos Principle Explained!

Or read the full The Talos Principle article!

This post is part of a larger deep dive

Curious about the role of the nature of consciousness and free will in The Talos Principle? Check out The Talos Principle Explained!

Or read the full The Talos Principle article!

Consciousness is such a difficult concept to define that it is perhaps easier to begin this discussion by describing what isn’t required for something to be deemed conscious.

Because our conscious experiences are so intrinsically linked to our emotional states, memories, selective attention, language and self-introspection, it is only natural to consider them as quintessential for a conscious experience. However, plenty of scientific evidence now suggests that none of those things are necessary.

For example, individuals with lesions in brain regions critical for the retrieval of memories have profound deficits in episodic memory (such as remembering past events), but they are just as conscious as you or I. Similarly, if the insult occurs in brain regions responsible for language processing, these patients might show pronounced deficits in speech production/comprehension, but they are not less conscious of their surroundings than you or I.

Clever laboratory experiments with healthy participants have also provided convincing evidence that attention, emotions and self-introspection are not pre-requisites for consciousness.

Note, that I said they are not required, but that doesn’t mean they aren’t useful. As already mentioned, patients with severe memory deficits are surely conscious, but their impairments may reduce the quality of their conscious experiences.

So, how does the brain produce a conscious experience?

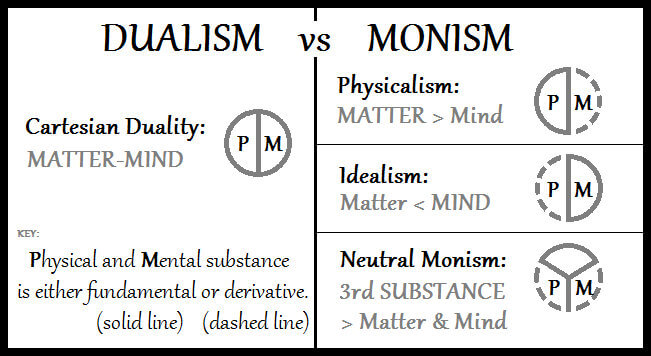

That’s pretty much the question that divides two prominent views in the philosophy of mind: monists and dualists. One specific monist view, physicalism, argues that all mental states and processes (including consciousness) are inherently physical (e.g., activation of specific neurons in the brain).

In contrast, dualists claim that mind (mental) and body (physical) are separate substances. According to this view, consciousness (a mind entity) is something physically intangible, not likely to ever be reduced to physical properties.

In a previous article, I discussed Thomas Nagel’s What is it like to be a bat?, which was largely written as a criticism to the physicalist idea. In this article, I’ll explain a physicalist framework for explaining consciousness.

In 2004, Italian neuroscientist Giulio Tononi proposed a theory of consciousness which he called Integrated Information Theory (IIT).

IIT rests on the idea that every conscious experience is unique, highly differentiated and consists of a huge amount of information. Watching my daughters play in the garden is a very different experience than watching a football match or listening to a Mahler’s symphony. Even similar events like listening to a Mahler’s symphony again, will be a unique experience on its own.

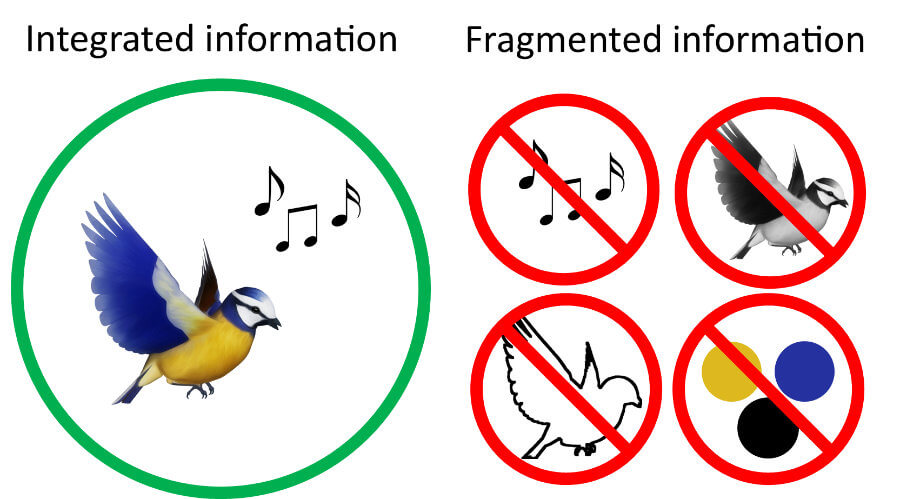

In addition, this information is also integrated. Let’s imagine we are looking at a bird singing (see figure above). We see the shape of the bird, its colours, its movements and chirping. We cannot only see the shape of bird, just as we are unable to see it in only black and white.

In other words, we experience the bird in its totality – we integrate all pieces of information, and that’s what we are conscious of. Our mind receives all these integrated information at once; they cannot be fragmented.

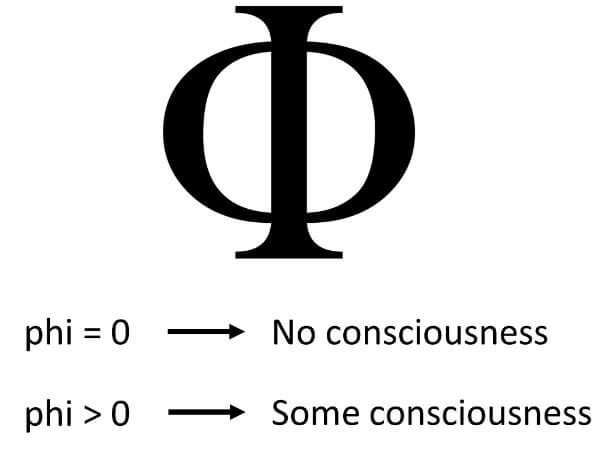

A system is a unique entity distinguishable from others, and it can be biological (e.g., an ant, a human) or not (e.g., a rock, a computer chip). IIT proposes a universal mathematical formula from which it derives a number, phi, that summarises the system’s degree of consciousness.

If a system possesses a high value of phi (measured in bits), the amount of integrated information in the system is very high, and, thus, will have a high degree of consciousness. In contrast, a value of phi close to zero is indicative that the system has a low amount of integrated information, and therefore has little to no consciousness.

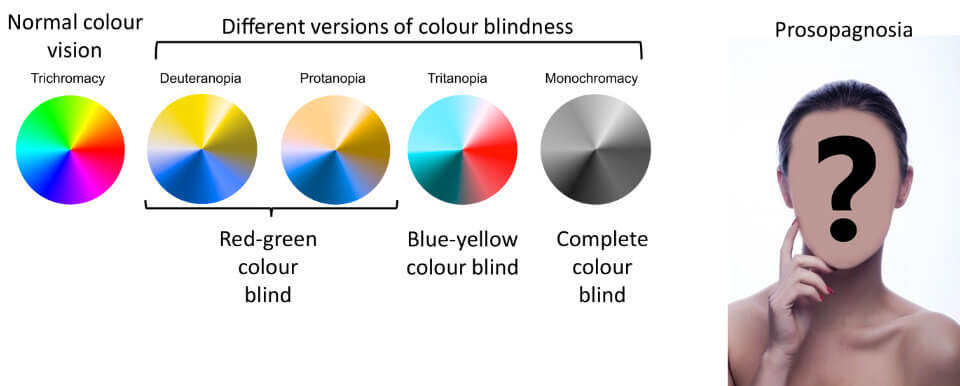

Many criticise the theory on the basis of brain lesions that alter perception in some individuals, thus questioning the idea of integration as crucial for a conscious experience. For example, some people with complete colour blindness will not able to see colours, only the shapes of things. Individuals with prosopagnosia have a deficit in recognising faces. Patients with this disorder are conscious that they are seeing a face (nose, eyes, mouth, etc.), but are unable to say whether two faces are the same or not.

Naturally, if certain brain regions responsible for one of these modules breaks down, then we experience disorders of consciousness. However, IIT proponents would argue that the conscious experience of those individuals is still integrated, the colour or face recognition just happens not to be a component of their experience.

If IIT is correct, then it would mean that everything in our universe will be guaranteed to have a phi which is above zero. So, a chimpanzee, a cat, an ant, a microbe, a tree, a microchip, and even a rock will possess a non-zero value of phi.

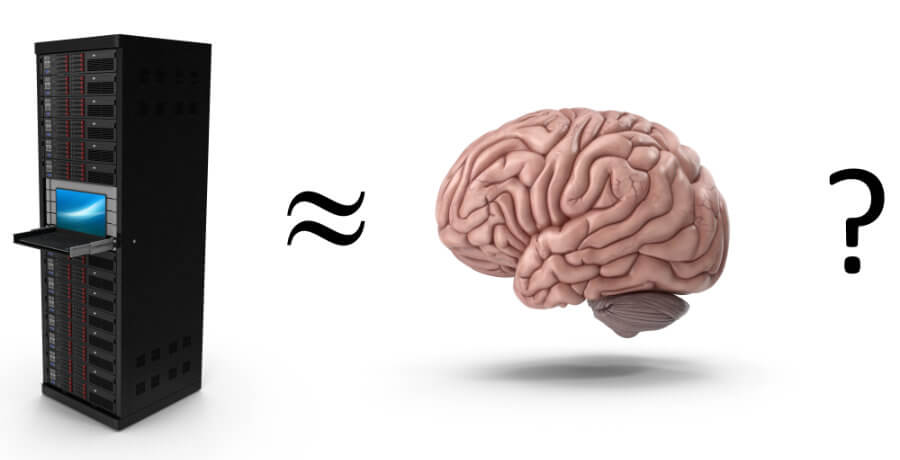

Thus, a computer will certainly also have a non-zero value of phi! But can it be conscious? The human brain is estimated to be able to store between 1 to 2500 terabytes and able to perform trillions of operations per second. My PC has about 4TB disk storage, so can I say my PC is as conscious as a kind of miniature human brain?

Of course not.

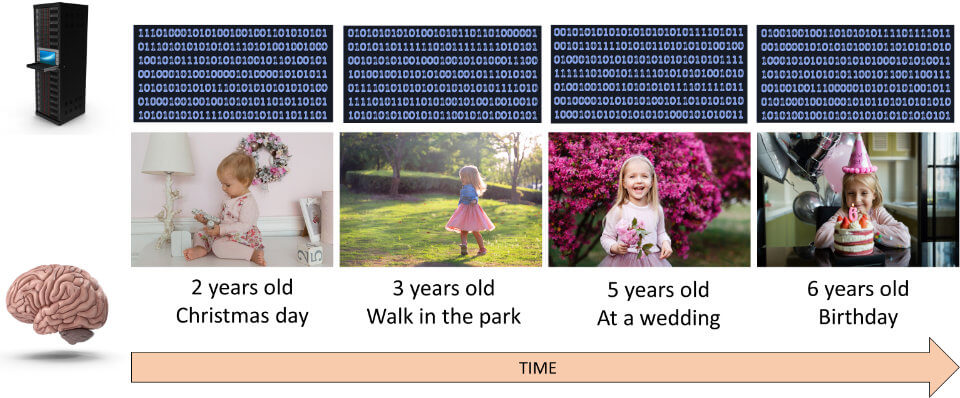

Even though we can associate a phi to my hard drive (i.e., phi > 0), the information that the drive contains isn’t integrated. Integration is the key word here. My PC has no clue that the photos I store of the recent birthday of my eldest daughter are related in time to the photos I took of her a week ago. In fact, to my PC, every photo of my daughter at different time periods of her life is independent, a bunch of zeros and ones that bear no relationship to the other photos.

To my brain, however, all of her photos are related; I have memories of seeing her yesterday, last year, when she was a baby, and these memories are all interconnected. The more this information is integrated, the more consciousness I have, and the higher the phi.

But, let’s imagine that we were somehow able to perfectly simulate a human brain in all its glory (the complete neural architecture down to every single synapse) using a conventional computer, would this simulation be conscious?

A tricky question, no doubt. I bet some of you have responded yes (I did, the first time I saw this question posed). After all, a healthy human brain is definitely conscious, so a perfect simulation of it must also be, right? Well, according to IIT, the answer is a categorical… No!

You see, a simulation is still limited by its underlying hardware. Each transistor connects to up to five other transistors of a particular type in order to get the system going. The human brain however, is way more complex than that. Even retrieving a simple memory may require the coordination of hundreds of thousands of neurons working together in different parts of the brain.

Famous neuroscientist Christoph Koch pointed out that just as simulating a black hole on the computer doesn’t distort time-space around it, simulating a human brain doesn’t make the simulation conscious.

Consciousness cannot be emulated, it has to be built into the system. So, we would need to replicate the causal effect structure of the brain, by building synapses and neurons using wiring or light for example.

In any case, IIT implies that an entity will have consciousness so long as it includes some mechanism that allows the entity to make choices among alternatives, in other words, that it has free will. Keep that in mind because it will be important for the analysis of the Talos Principle.

Leave a comment

Add Your Recommendations

Popular Tags