This post is part of a larger deep dive

Curious about the role of memory formation and retrieval in Memento? Check out Memento Explained!

Or read the full Memento article!

This post is part of a larger deep dive

Curious about the role of memory formation and retrieval in Memento? Check out Memento Explained!

Or read the full Memento article!

Memory is really what defines us. It is because we can form, store and retrieve memories that we are able to understand, feel emotions and even move and speak.

But, and despite often being described so, don’t think of memory as something akin to a hard drive on your laptop. Memories are not perfect accurate records stored in one particular comparment in the brain like files on a computer’s hard drive.

In fact, memories are complex and extremely interconnected neural networks that spread over the entire brain.

Memories are also fragile and subject to change over time. A vivid memory of an event when you were 10 years old has most likely been altered over the course of the years. This may happen due to a combination of your own residual remembrance of the event, others’ account of the event, or even similar recent events that you might have experienced and got mingled with the older memory.

In the next section I’ll give a very brief scholarly introduction to the organisation of memory, and the division between long-term memory (the memory system that allows you to retain information over extended periods of time) and short-term memory (the memory system that stores information for brief duration).

Every memory you have that goes back for longer than a a few minutes is most probably stored in your long-term memory, regardless of whether you are aware of them or not.

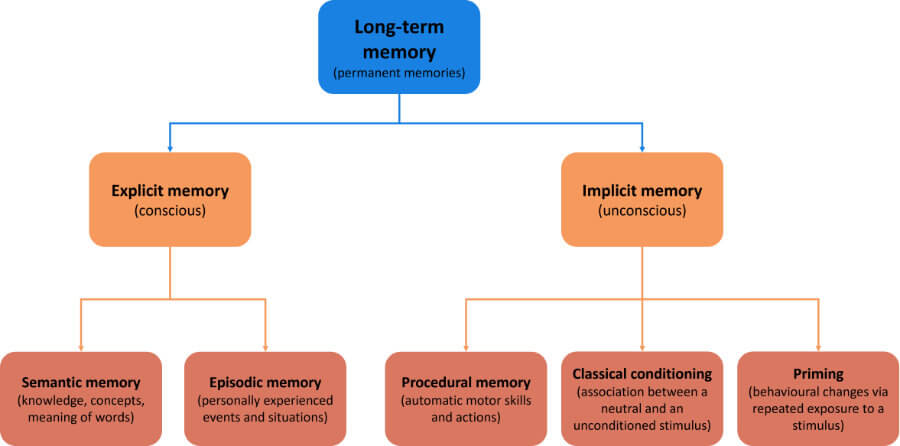

Cognitive scientists have found it helpful to divide long-term memory into two big sub-types: explicit memory and implicit memory. The difference has to do with the role of consciousness, that is, whether memories are being retrieved intentionally (explicitly) or automatically (implicitly).

Explicit memory are those memories that you can consciously and intentionally bring back and which can be expressed with language. That is why it is also known as declarative memory – because you “declare” (using language to describe) facts and events.

Explicit (or declarative) memory is further divided into 2 sub-types: semantic and episodic memory.

Semantic memory stores the memories you have of words, concepts and objects. For example, the meaning of the word troglodyte, the capital of France, the name of the object that you sleep on at night (bed), etc. Whenever you attempt to retrieve the meaning of any of these words you are using semantic memory.

Episodic memory refers to memories that you can consciously invoke and which you’ve personally experienced in some place and at some point in time. These include our own past experiences, thoughts and wishes (which together form the autobiographical memory), as well as memories in which we were simply witnesses (e.g., the memory of watching John fall down the stairs).

Note the important distinction between semantic and episodic memory: semantic memory doesn’t have a personal component (e.g., there isn’t anything you personally experienced when you’re simply trying to retrieve the name of the capital of France), whereas episodic memory does.

Implicit memory consists of memories which we can bring back without the aid of consciousness. This implies that you can “remember” something which you are not really aware that you have retrieved.

The prototypical example of an implicit memory is that of driving. You can talk to your friend seating on the passenger seat and listen to a good old song on the radio, all the while you are performing complex maneuvers on a busy city street.

Imagine the disaster it would be if you had to consciously focus on every single one of these driving actions. By the time you finished gearing up you could have missed the stop sign. However, you’re able to pay attention to the street, while your hands and feet do what they are supposed to do automatically.

There are many types of implicit memory, but three of the most studied are procedural memory, priming and classical conditioning.

Procedural memories are related to motor skills learned through repetition, such as driving, tie a shoe or brushing your teeth. Once you have acquired the skill, these memories can be retrieved automatically, without the need to consciously supervise the action.

Priming is a phenomenon that occurs when your response to a stimulus changes because you have been exposed to it before. Imagine that during the day I bombard you with subtle cues that point to a specific number (e.g., the number 55), but are nonetheless unconsciously registered by your brain. Then, later in the day we are watching an American football match, and I ask you to pick any player, betting that I can guess the number of the player you’ll pick. Lo and behold, you pick the player with the number 55 – you’ve been primed! (btw, I took this example from the movie Focus, starring Will Smith and Margot Robbie – click here to see the scene, and here for the explanation why it worked).

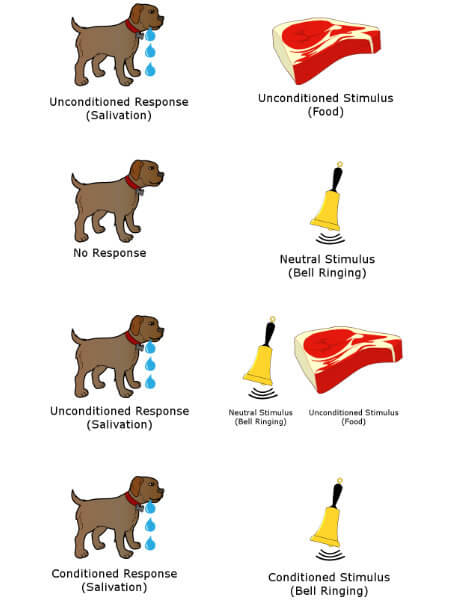

Classical conditioning is the association between a neutral stimulus (something which usually doesn’t trigger any particular response) and an unconditioned stimulus (something that leads to an automatic response, such as fear; see figure above). For example, let’s say someone gives you a shock every time a bell rings. The bell is a neutral stimulus at first, because on its own it wouldn’t normally trigger a particular response on you. However, if paired with an unconditioned stimulus (e.g., the shock), you might start becoming anxious every time the bell rings, even before you get the shock – you’ve been conditioned!

Both priming and classical conditioning are thought to be implicit memories because they can be retrieved relatively automatically and effortlessly. However, it’s still debatable whether implicit memory is truly an independent system from explicit memory.

Whereas the duration of long-term memories can last a lifetime, information in short-term memory can only be retained for about 15-30 seconds. If you can remember something that you have witnessed a few minutes ago, it is not in your short-term memory anymore but likely in your long-term memory.

Most explanations of short-term memory almost always use the example of keeping a phone number in mind. When someone recites you a phone number for you to dial in a few seconds, this information enters short-term memory.

For something to be registered in your short-term memory, you need to pay attention to it though.

So, if you are sitting in a cafe, and look at the person sitting next to you, it will be registered in your short-term memory. The menu you just read will be coded in short-term memory along with the typeface used, images, the commercial you see on TV, the name on the name tag of the waitress and so forth. Literally everything you give enough attention go through short-term memory.

Now, in every day life, it is more relevant to speak of a “working memory”, rather than short-term memory. The distinction is subtle but important.

When psychologists refer to short-term memory they are usually referring to the capacity of the storage: 15-30 seconds and up to 7 units of information (e.g., 7 numbers).

Working memory, on the other hand, is a brain system where you can process and manipulate information in short-term memory for a bit longer. If you are having a conversation with a friend, it’s probably useful to maintain information in your brain for longer than 30 seconds. Otherwise, you would always lose the thread of the conversation.

Most information that enters the brain will be forgotten. Tomorrow, you will have probably forgotten the menu, the person sitting next to you, the TV commercial and the name of the waitress from the day before.

Note, however, that forgetting things from the day before doesn’t necessarily mean they were short-term memories. They could have been momentarily transferred to long-term memory, but because the information wasn’t consolidated strongly enough in long-term memory, it was easily forgotten. Important memories (such as those carrying emotional content) tend to be transferred to long-term memory (see section below).

Note that although short-term/working memory is regarded as a separate system from long-term memory, it can interact with it by retrieving task-relevant information stored in long-term memory. Think about it: it would be very hard to follow a conversation about cars if you didn’t know what a car is. So, working memory needs access to semantic knowledge stored in long-term memory in order to make sense of the information.

You might wonder why have psychologists bothered using divisions like short-term vs. long-term memory, implicit vs. explicit memory and so on. Why not simply categorise everything in a single memory system and be done with it?

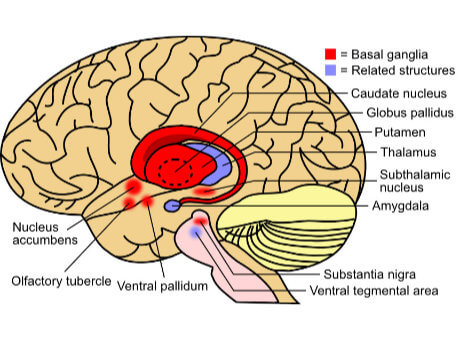

Researchers believe that the brain contains different memory systems that are more or less independent from one another. Many experimental studies with patients with brain lesions revealed that some types of memory are disrupted if specific brain areas are impaired.

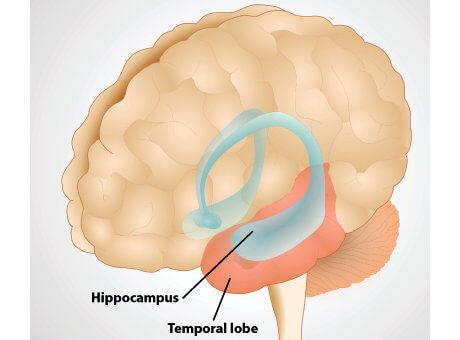

One of such brain regions are the medial temporal lobes. Famous patient H.M. suffered from severe epileptic seizures as a result of a bicycle accident as a child. In an attempt to alleviate and possibly cure his epilepsy, HM underwent a surgical procedure to remove both of his medial temporal lobes.

The procedure was successfully in controlling his seizures. Nevertheless, H.M. lost the ability to form new explicit memories: he could not remember any new information for longer than a few minutes.

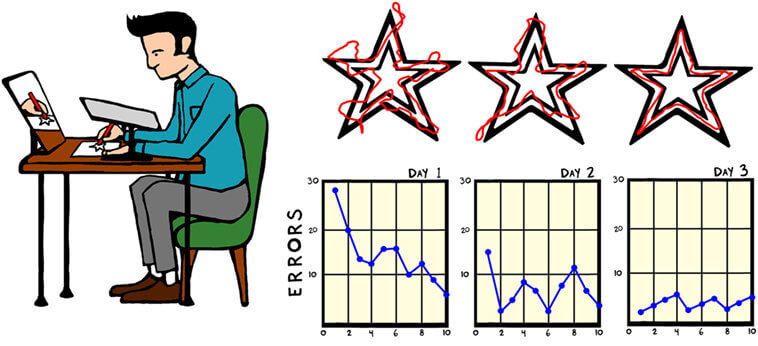

Surprisingly, his implicit memory was intact. Researchers asked H.M. to trace a line between two five-pointed star by only looking at his hand through a mirror (see figure above). With practice, his tracing got increasingly better over the course of the days, even though he was unable to remember that he ever did that task previously.

Likewise, his short-term/working memory remained intact. He could obviously follow the instructions the experimenter was giving, which is exactly the kind of job the short-memory is for.

So, H.M.’s memory deficit was in his long-term memory, more specifically, in his episodic memory (his semantic memory was partially affected). Whether his deficit was due to a failure during encoding, storage, retrieval, or a combination thereof is still a matter of much debate.

Cases such H.M.’s have helped researchers gain a better understanding of how memory is organised and led to the development of extant theories relating the structure and function of the brain to specific psychological processes.

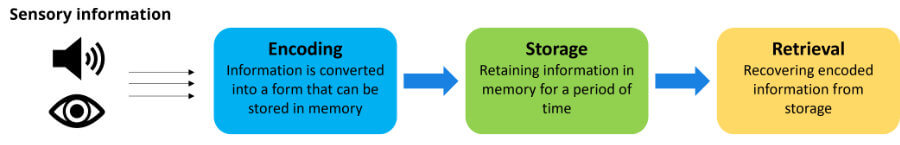

For a memory to go from short-term memory (memories that last for up to 30 seconds) to long-term memory, it needs to go through 3 stages: encoding, storage and retrieval.

Encoding refers to how the sensory inputs (e.g., the visual words in a menu) are converted to an input that can be stored in the form of a memory. Think about what happens when you press the “A” key on a computer keyboard. The computer doesn’t know if you typed an “A”. The pressing of the “A” key (sensory information) is converted into a digital signal that the computer (your brain) will understand.

Storage refers to the ability to maintain the information you just encoded. Keeping with the computer analogy, this would be equivalent in clicking the save button, so that a file is stored in the computer.

Retrieval is the ability to access the stored information whenever you need it. Again, using a computing analogy, this would be like going to the file and open it up so that you can read its contents.

Now, encoding, storage and retrieval are not discrete, isolated processes. In fact, encoding and retrieval are strictly intertwined, and the brain mechanisms responsible for each may overlap to a great extent.

If you direct your attention to a particular object, you will likely encode it visually and will bring the information to short-term memory. If you need to maintain that information for a short while it will be dealt with by your working memory. However, as discussed above, information in working memory is volatile, so it might quickly vanish (and most information we pay attention to is indeed lost).

However, if the information is deemed to be sufficiently significant, it will be stored in long-term memory (storage process). Consequently, you’ll be able to retrieve it if the information has been successfuly stored (retrieval process).

For example, if you have encoded a phone number just for the purpose of dialing it in the next few seconds, this information will be placed in short-term/working memory. But because this information is not really useful anymore, it will not likely be stored in long-term memory, and, therefore, you will not be able to retrieve it ever again.

In contrast, imagine you are walking down the street and someone steals your bag. Because of the significance of this event, your brain will give it a high priority and will transfer this memory to long-term memory (via the storage process).

It’s quite normal to forget things. As we age, we also show an inevitable decline in our ability to remember. This is a normal consequence of aging and even though gradual memory loss is inevitable, there are certainly ways to delay it.

Unfortunately, for some people, their memory problems are much more severe, leading to a complete inability to recover memories of the past or form new ones.

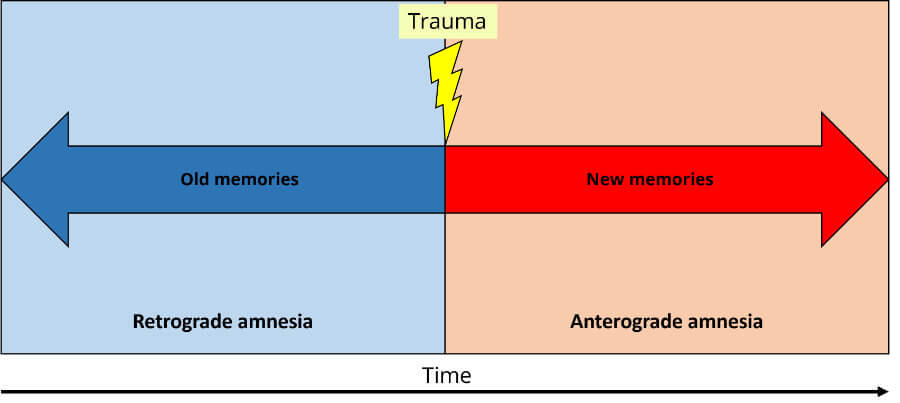

Neurologists have identified several types of amnesia depending on the type of insult to the brain and the extent of memory loss. In this secion, I’ll mention two specific types of amnesia: anterograde and retrograde amnesia.

If an individual is unable to remember events before the lesion, the patient will have retrograde amnesia. For example, H.M. was unable to retrieve any memories 3 years before the surgery, suggesting a partial retrograde amnesia.

If, in contrast, the individual is unable to remember events that take place after the lesion, then the patient will have anterograde amnesia. For example, even though Brenda Milner worked with H.M. for over 20 years, she always had to introduce herself to him, because he had absolutely no recollection of having ever met her.

Anterograde amnesia is by far more common than pure retrograde amnesia, and even rarer are patients with both forms of amnesia (such as patient H.M.)

Although H.M.’s amnesia was the result of a surgical procedure, amnesia can have other causes, for example, traumatic head injuries, dementia and encephalitis.

Finally, if the amnesia is accompanied by the presence of structural lesions to the brain (e.g., as a result of trauma to the head) it’s called organic amnesia. If there is no identifiable brain damage, then the amnesia is due to psychological factors (e.g., extreme stress), and it’s called psychogenic amnesia. Psychogenic amnesia is mostly associated with an inability to retrieve past memories (i.e., retrograde amnesia) but it can also affect the formation of new memories, although it’s extremely rare.

Masterpiece

amazing

amazing. 5-stars. blown away. great storytelling and structure. crazy twist, one of my favourite movies ever. youd never see it coming and its quite tragic when you think about it

Completely agree! Is there a particular interpretation of the ending you gravitate towards?

By the way, that was a very fitting name you have chosen 😀