This post is part of a larger deep dive

Curious about the role of Hegelian dialectic in Hegel’s Holiday?

Read the full Hegel’s Holiday article!

This post is part of a larger deep dive

Curious about the role of Hegelian dialectic in Hegel’s Holiday?

Read the full Hegel’s Holiday article!

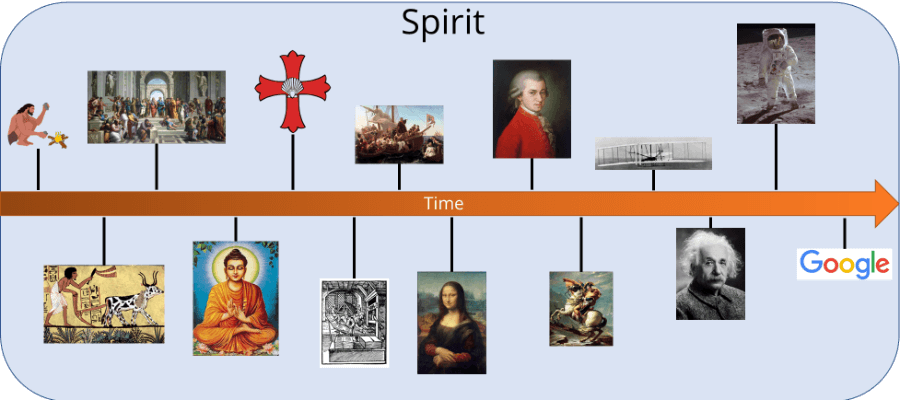

According to Hegel, all phenomena (e.g., consciousness, political institutions, tradition, culture, etc) are all aspects of an entity that he calls Spirit (Geist in German).

As I understand it, Spirit is essentially the sum of everything that has to do with humanity, including human expressions, thoughts, desires, language, goals and so on. These are grouped under a single overarching term: ideas or mind.

To Hegel, ideas are never fixed, they are constantly changing. This is clear when you look at world history; language, science, law, social institutions, attitudes, traditions have been changing throughout the course of history.

So, what we experience as history is nothing more than Spirit moving through time, driving things forward, and keeping the world in a constant flux.

Spirit’s end goal is actualising itself. That just means that, through human activity, Spirit gradually becomes more self-conscious, it evolves into what Hegel calls the Absolute Spirit (more on that below), where things get more collective and unified.

The way Spirit self-actualises is through a process called the dialectic.

Dialectic comes from the Ancient Greek word diá which means “through” and lektikós, which means good at speaking, able to speak, the art of speaking. So, putting together diá and lektikós gives us more or less this translation: (something can be attained) via the ability to speak well”.

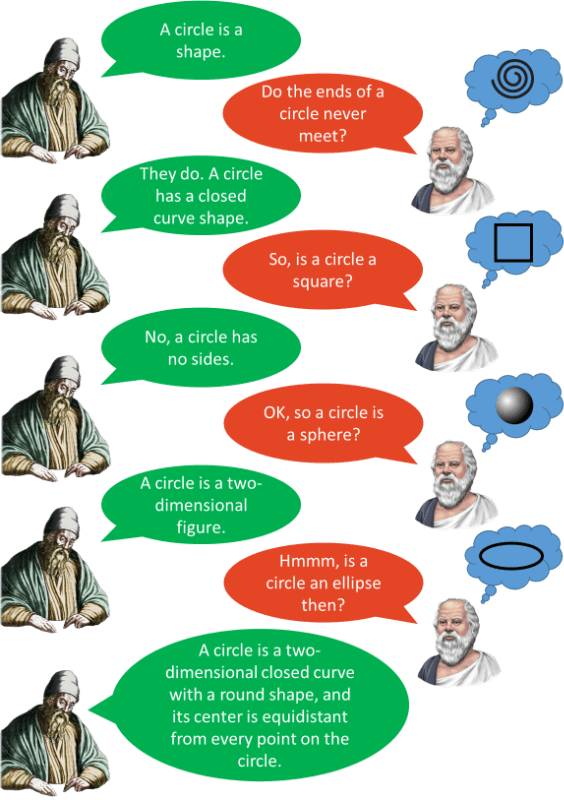

Dialectics had already been in use since Plato. Plato believed that people could achieve knowledge by engaging in conversations. He exemplifies his dialectic method by imagining Socrates asking a series of methodical questions to his interlocutors, mostly pointing out any flaws or incongruities in their reasoning. Socrates’ oppositions are an attempt to establish the truth on the topic being discussed.

So, the dialectic is really just a method in which ideas are opposed to each other, with the aim to gain truer knowledge.

Hegel’s dialectic is shaped around the idea that everything that exists, including an object, a person, a consciousness, a government, an idea, contains within itself a contradiction (or negation).

Think of a contradiction as an action or an idea that causes the original object to transform itself.

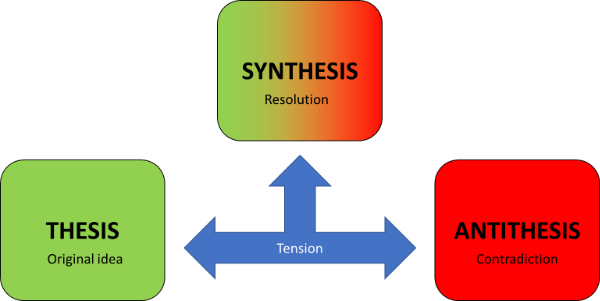

Hegel’s logic starts with two notions that are mutually incompatible. For every notion (or thesis) there is a contradiction (an antithesis). The tension between thesis and antithesis is resolved by the emergence of a higher-level stage (synthesis – Aufhebung or sublation).

Note that the antithesis doesn’t necessarily need to be the exact opposite of a thesis – it just needs to put the thesis into question. Hegel believed that it usually takes three moves for the resolve to be found.

If you go to youtube and check Hegellian dialectic video explainers, chances are that you will come across a video lauching a tirade of criticism against the use of the thesis-antithesis-synthesis triad as an explanation for Hegel’s dialectic.

It’s true that Hegel never used that formulation to describe his dialectical method. The thesis-antithesis-synthesis triad was originally proposed by Immanuel Kant and further refined by Johann Gottlieb Fichte and Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling.

Critics might evoke several reasons such as the meaning of the word synthesis bringing to mind the idea of combining or mixing things together. Hegel was careful to point out that the end result of his dialectical method is not a compromise of two things, or even their merging. Rather, the end result should be something greater, something that is elevated above and beyond the original notions.

Fair enough. However, Hegel’s ideas are already pretty complicated as they are, and opened to interpretation. Therefore, I don’t see the issue in trying to simplify some of these concepts, as long as we are aware of the limitations of using such nomencleture.

Frankly, I have yet to see a better explanation of Hegellian dialectic that does not employ the use of the thesis-antithesis-synthesis triad.

In fact, Hegel’s pundits often use terms such as Abstract-Negative-Concrete, which, in my opinion, are not only completely non-intuitive and vague, but you could even argue that using these terms is just as debatable. Hegel wrote in German, and the German words he used were “die abstrakte/verständige” (abstract/understand), “die dialektische/negativ-vernünftige” (dialectic/negative reason), “die spekulative/positiv-vernünftige” (speculative/positive reason), for Abstract, Negative, and Concrete, respectively.

So, unless a compelling argument can be made for employing particular English words as opposed to others, I believe we are caught up in semantics, which, for a newbie in Hegellian philosophy like myself, is a deterrent to the understanding.

Also, making sense of Hegel’s texts likely requires a PhD in Philosophy. But for the rest of us, we can surely benefit from the thesis-antithesis-synthesis idea, which has proven to be a good heuristic for learning Hegel’s dialectic, and also the preferred method of teaching Hegellian dialectic by reputable scholars.

Hegellian purists might completely disagree with me but, in my opinion, if the thesis-antithesis-synthesis triad not only provides a more intutive grasp of the Hegellian dialectic, but also proves to be didactically superior, then I think it’s only reasonable to make use of it.

It’s important to remember that the dialectics does not happen on an occasional and disjointed basis.

In fact, it takes place all the time whenever two objects (and by that I mean two ideas within an individual, two individuals, an individual and a rock, two institutions, two religions, etc) interact and create tension.

And when a synthesis is generated, it becomes the new thesis which gets contradicted and develops into a synthesis and so on and so forth.

Note that the original thesis and antithesis are not destroyed. Rather, these oppositions are preserved at a higher level. Indeed, when sublation is successful, two things occur: negation and preservation. The tension between opposites is both negated and preserved. It has a partial truth to it which exists within the superseded notion.

It’s important to realise that the synthesis isn’t simply mutating things together. It’s not like we are trying to find a compromise between a thing and its opposite (by the way, I believe this is the reason why people often avoid talking about a synthesis-antithesis-synthesis when discussing Hegel).

So, we are not looking for a compromise. When we start with a notion (thesis), apply a contradiction (antithesis), the resulting notion (synthesis) should be an elevated form of the original notion.

In addition, the synthesis is not something from the outside that resolves the apparent contradiction. The synthesis emerges from the original notion and its contradiction, so it is really one aspect of a three-part notion (thesis-antithesis-synthesis). That means that old notions have the potentiality already in them, and the synthesis is simply the actualisation of that potentiality.

Likewise, the contradiction of the idea is internal to the original idea itself. To illustrate this, think of the concept of freedom. Few people would disagree that freedom is essential and should be pursued by every human being. However, even freedom can be abused, as in the case of land/business owners calling upon their “freedom” to exploit and oppress their employees. So freedom has within itself a contradiction – oppression.

The successful transformation of a seed to an oak tree requires several factors such as sunlight, water, and adequate soil. However, if the seed is not yet ready to contradict (or transform) itself, it will remain a seed, regardless of the conditions in its environment. So, the transformation (contradiction) of the seed is totally internal to the seed, and not due to external factors – this is what Hegel means by everything that exists is contradictory in itself.

Unfortunately, practical examples of Hegel’s dialectics are relatively scarce. But I like to work with practical examples, so I’ll give my best shot.

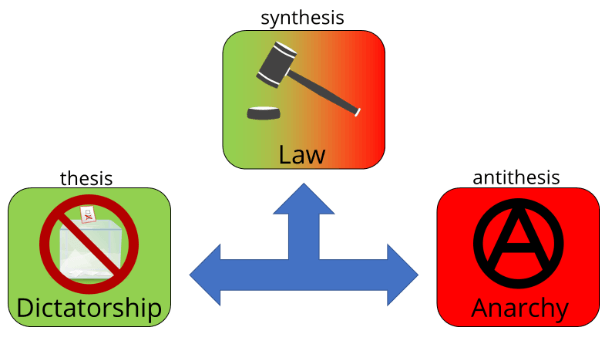

Let’s think of the case of a dictatorship (thesis). People are often discontent with this kind of government, so it generates the need for freedom. The dictatorship could get opposed by a form of government with total political freedom – anarchy (antithesis). Now, if you combine an element of dictatorship with an element of anarchy you create law and a democratic government (synthesis), which is, by most accounts, a superior form of government.

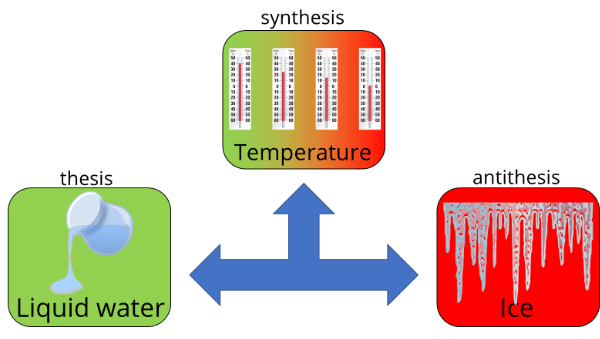

Let’s say you run an experiment and the results tell you that water is a liquid (thesis). However, additional experimentation reveals that water can be solid as well (antithesis). By reasoning (combining elements of both the thesis and antithesis), you reach the conclusion that water can be both liquid and solid, depending on the temperature (synthesis). So, based on observation and experimentation, you reached a conclusion that is more accurate.

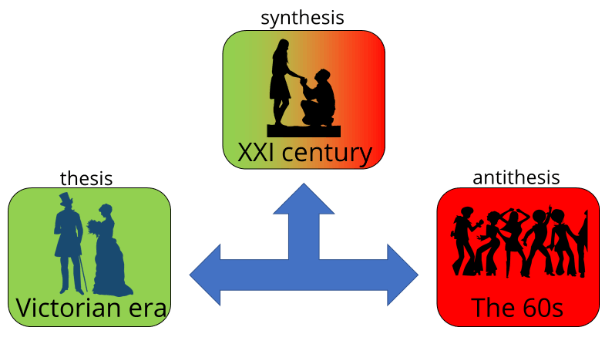

The Victorian era was famous for its puritanical and repressive attitude towards sexuality (thesis). This led to a natural increase in sexual freedom, which resulted in the extreme liberal stance on sex of the 1960s (antithesis). A balance has been restored in our current decade (synthesis), since we now have sexual freedom but (most of us) restrict its use to intimate settings.

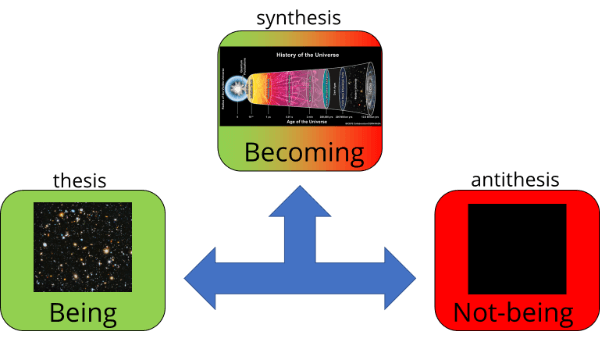

Hegel put forth the notion of “being” (thesis). This concept however contains a contradiction, because something that exists will not exist and has not existed forever. So, to grasp the notion of being requires the idea of nothingness, or not-being (antithesis). How is this contradiction resolved? The concepts of “being” and “not-being” are two aspects of a superseded concept: becoming. That is, the state of “not-being” moves to (or becomes) a state of “being”.

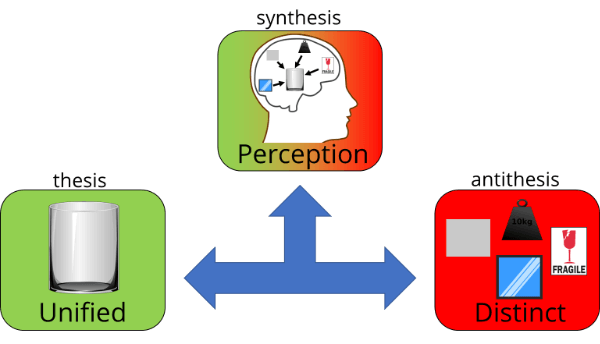

When I see a glass on a table, I perceive the glass in its entirety, as a single entity (thesis). However, my wife points out that the glass isn’t a unified object. It actually contains different properties such as shape, colour, transparency, weight, texture and so on (antithesis). True, but despite the many properties of the glass, our human brain is hardwired to perceive the glass as one single entity (synthesis).

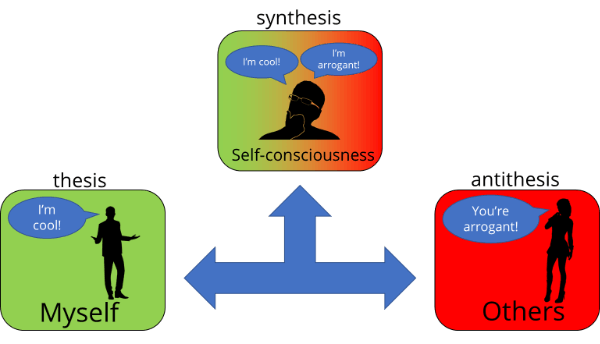

Let’s say I feel like I’m a very confident person (thesis). However, I interact with other people in this world, and they will have formed an opinion about myself, maybe that I’m arrogant (antithesis). So, in order to gain a better understanding of myself, I should try to see how others see me, without, of course, loosing sight of what I think about myself. If I allow this tension to play out (the tension between what I believe I am, and how others see me), it’s just possible that I’ll become closer to understand who I’m truly are, and reach self-consciousness (synthesis).

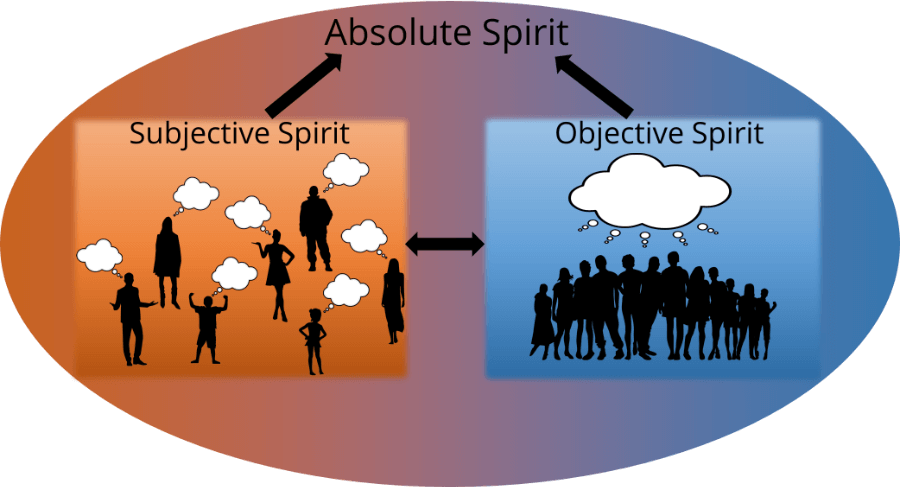

The dialectic begins with individuals gaining self-consciousness, that is, being aware of himself/herself as an individual among other people (see example 5 above). This is Subjective Spirit, according to Hegel, and happens within the mind of an individual (hence subjective).

You can think of subjective Spirit as the individual interests, desires and objectives in life. When you try to fulfill those desires and goals you are contributing to the self-actualisation of Spirit

The dialectic evolves to encompass the consciousness of social and political groups, tradition and culture. Hegel calls this the Objective Spirit.

The objective Spirit is, thus, ideas that are shared among all people. For example, humans seem to possess concepts such as tradition, culture and society, regardless of the environment they were brought in. As such, tradition, culture and society are all aspects of the Objective Spirit.

And it is objective Spirit (ideas shared among people) that end up shaping our own individual perception of reality. Thus, we interact and engage with the world around us through ideas that are shared among human beings (i.e., objective Spirit).

To Hegel, the dialectical process on both the Subjective and Objective Spirit continues in this way, always refining itself, with the aim to reach an end point. That end point is the Absolute Spirit, the reconciliation of Subjective with Objective Spirit (the totality).

The Absolute Spirit is a kind of consciousness that belongs to reality as a whole (and not to any single individual). When Spirit reaches this stage, we can say that knowledge is complete. I believe this means that humanity reached a sort of nirvana, where societies flourish in peace and humans behave completely rationally.

If there is something that drives me mad is the sort of tricky phrases that explain concepts in riddles. Why really?!?

For a long time, the phrase negation of a negation looked like one of them, but I will try to break it down and show it to you that it isn’t really that bad (provided, of course, I’m getting the concept right myself).

To explain what the negation of a negation in Hegel’s philosophy means, let me give you an example using science (thanks to Alison Adams, for a great explanation here).

The way science develops is through a continual dialectic: scientists come up with a reasonable theory (thesis), which is confronted with a contradiction (antithesis), that results in a new theory (synthesis). That theory (now itself a thesis) gets contradicted again (antithesis), creating a new theory (synthesis) and so on and so forth.

Hegel’s fabulous insight was that these contradictions do not simply update the original ideas; contradictions are actually the agent that allow the original ideas to develop into a higher level.

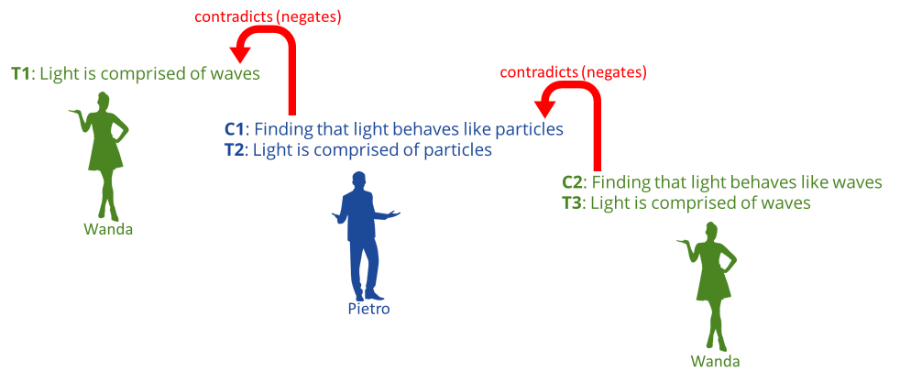

Imagine that a scientist called Wanda has a hunch that light is comprised of waves. Let’s call that theory 1 (or T1).

Then, another scientist, Pietro, carries out an experiment and finds that light behaves like tiny particles, and so, this finding contradicts T1 (let’s call that contradiction C1). So, Pietro proposes a new theory that states that light is made of tiny particles instead (T2).

However, Wanda decides to devise an experiment herself, which turns out to contradict the idea that light behaves like particles (this is C2). Then, she revives her previous theory that suggests that light really behaves like waves (T3).

So, one could conclude that T1 = T3 since they both claim that light consists of waves. If so, we should also conclude that if C1 contradicts T1, then C1 should also contradict T3 (since T1 and T3 are equivalent). This means you could simply apply C1 to whatever further claim that light behaves like waves.

But that clearly won’t work. C1 was already contradicted by C2, and, thus, C1 does not have the potential to modify the state of T3.

So what is going on here? What makes T1 and T3 different?

They differ in that T3 is the result of a historical progress. T3 contains in itself a history, in which C1 and C2 became parts of it. T1 does not have this history, and that is the key.

This is actually very relevant in my example. Light can actually behave both as a wave and as a particle, depending on the experimental set-up you use to detect it.

T3 has synthethised all the previous findings, so Wanda can forge a new theory that suggests that light can behave both like particles or like waves, depending on the type of experiment that is carried out.

In other words, T3 contains both thesis (T1 and T2) and antithesis (C1 and C2) and incorporates that information, that history, into itself, whereas T1 does not. That is the difference between T1 and T3.

Now we are in a good position to understand what a negation of a negation means.

Remember that C1 (the finding that light does not behave like a wave) is the negation of T1 (the theory that proposes that light behaves like a wave). On the other hand, C2 (the finding that proves that light behaves like a wave) is the logical negation of C1 (the finding that light does not behave like a wave).

So, if C2 is the negation of C1, and C1 is the negation of T1, then C2 is a negation of a negation.

C2 (which leads to T3) is essentially the synthesis of this whole story. So, the synthesis is the negation of a negation.

Pheeww…

OK, that’s enough of Hegel for today (and probably for years to come)!

Leave a comment

Add Your Recommendations

Popular Tags