This post is part of a larger deep dive

Curious about the role of conscious experience in Being John Malkovich? Check out Being John Malkovich Explained!

Or read the full Being John Malkovich article!

This post is part of a larger deep dive

Curious about the role of conscious experience in Being John Malkovich? Check out Being John Malkovich Explained!

Or read the full Being John Malkovich article!

In all honesty, the field of philosophy is riddled with overly complicated jargon that only philosophers appear to appreciate: epistemological pluralism, collectivist perspectivism, deontological ethics, metaphysical idealism… You name it. Throw in borrowed German words such as: Ding an sich, Übermensch, Aufhebung, Zeitgeist, and no wonder philosophical texts look all Greek to us!

There is, however, one philosophical domain that is very relevant to the analysis of “Being John Malkovich” so it might be worth to remember: phenomenology.

Succinctly put, phenomenology is the studying of conscious experiences as we experience them from a first-person perspective.

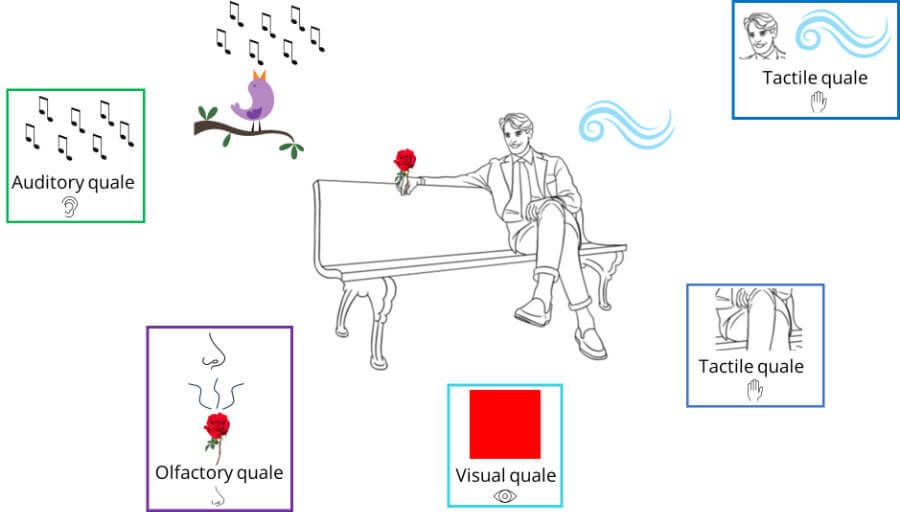

Let’s imagine I’m sitting on a bench, looking at a red rose, thinking about how to explain what phenomenology is, feeling the wind on my face and hearing the birds chirping.

Now, this phenomenological experience can be decomposed into separate, elementary properties, known as qualia (singular: quale). So, the quale of the red colour of the rose is the subjective sensation of seeing red. The texture of the rose petals or the way my buttocks feel while sitting on the bench are tactile qualia; the sound of the birds is an auditory quale, etc. All of these qualia are the properties of my current phenomenological (conscious) experience.

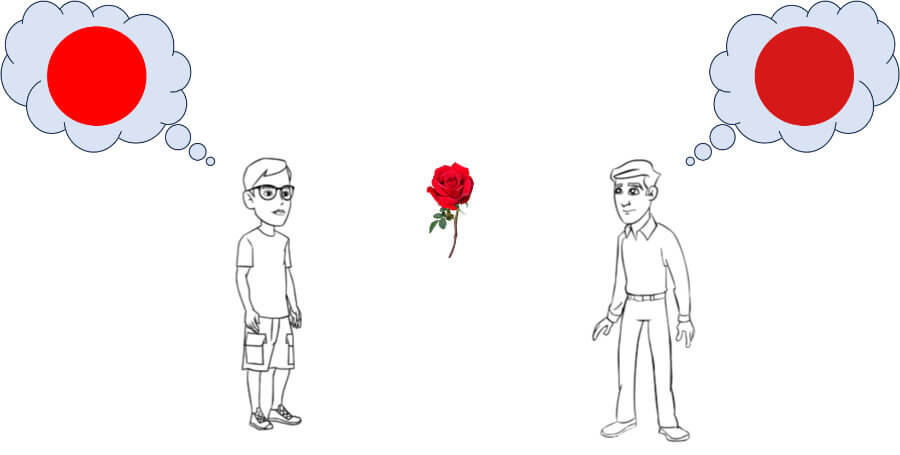

The qualia are unique to each individual; when I have a subjective experience of something, the qualia of that experience can only be experienced by me. Even if you are looking at the same red rose, what “red” feels to me might be different from what “red” feels to you (for example, I might perceive it as slightly brighter, more pleasant, etc.).

Furthermore, even if I can describe my qualia to you in the most detailed way possible, that alone isn’t sufficient for you to know my own subjective experience.

Now, reductive physicalists (to introduce yet another jargon term) argue that everything can be reduced to physical phenomena. They argue that maybe we cannot yet completely explain consciousness because our experimental tools are still too crude, but we might eventually be able to do it in the distant future.

Thus, physicalists believe that consciousness, just like any other product of the mind, can be reduced to properties of the physical brain (neuronal firing, chemical interactions among neurons, inter-areal communication, etc).

But…

What a weird question for a title!!

Yes, it is weird. But it just so happens to be at the center of a great debate, if not the most exciting debate, in the entire field of cognitive science: the hard problem of consciousness.

The very same question in the title above was also the title of a 1974 paper by American philosopher Thomas Nagel. Basically, it deals with the tricky question of what it means to have subjective conscious experiences, and how a physical substance, such as the brain, can give rise to these subjective conscious experiences.

Nagel criticised physicalists’ position that consciousness is ultimately physical. To Nagel, consciousness isn’t something tangible that we can objectively measure with scientific tools, which is what physicalists attempt to do. He argued that, by trying to measure something objectively, we are removing subjectiveness from the equation. If there is no “subjective” in subjective experience, then physicalists cannot explain those experiences.

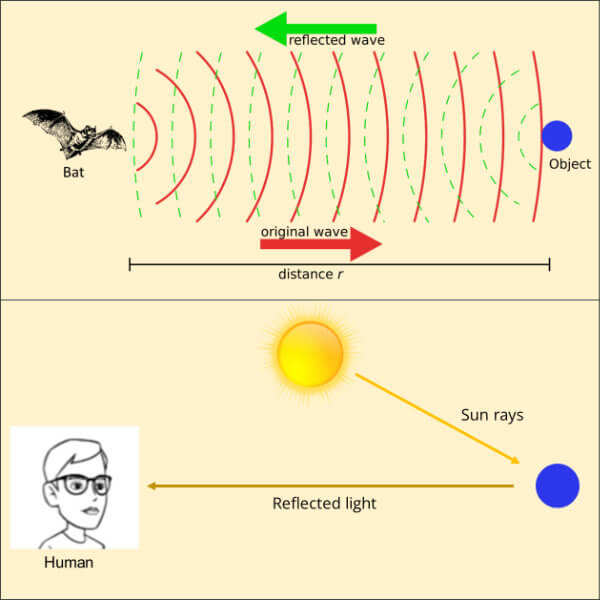

Nagel famously defined consciousness as “the feeling of what it is like to be something”. He reasoned that it’s likely that not every living being is conscious, but he felt that bats probably are. Bats are mammals, just like us, but unlike us, see the world in a very different way.

For starters, whereas humans are diurnal and rely on sight to navigate the world, (most) bats are nocturnal with relatively poor eyesight, relying instead on echolocation to find food and avoid obstacles.

He goes on to argue that we can never really know what it is like to be a bat, just as we will never be able to truly experience the what it is like to be someone else. In fact, we will not be able to experience anything in itself. So studying the subjective experiences with objective methods is simply impossible according to Nagel.

You might counterargue and say that you can imagine how a bat must feel like. For example, if you’ve already done skydiving or bungee jumping, you may have an idea of what flying probably feels like. Also, even though you cannot echolocate, you can imagine throwing a series of objects and if they ricochet and hit you, you know there is a wall in front of you.

But herein lies the problem. You are experiencing these things from the perspective of a human. No matter how sophisticated your experiences are, and how well you describe them, you are experiencing them and describing them from your point of view. You still cannot know exactly what it feels like to be the bat (i.e., the bat’s qualia), because those qualia are simply inaccessible to you.

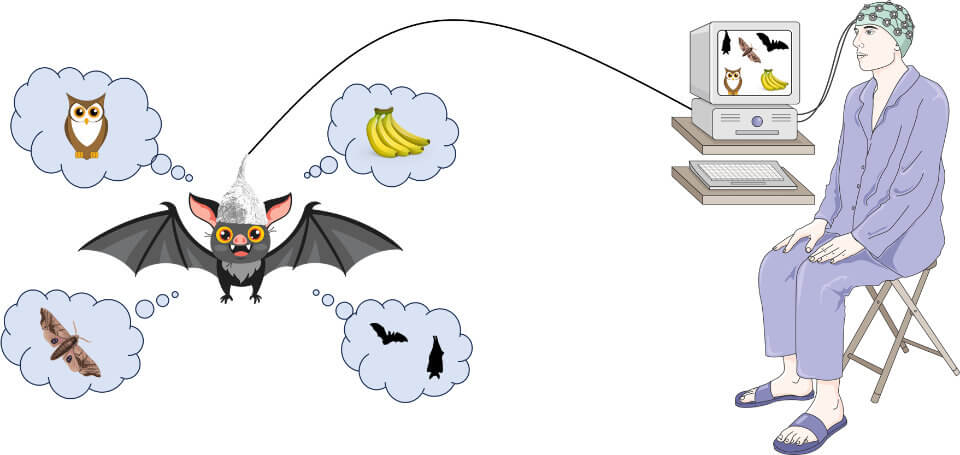

One could even potentially bring up the argument that in the future we might be able to build a sophisticated machine that would be capable of analysing the bat’s neural circuitry while conscious, generate its qualia, and insert them into your brain. Then, surely, you would feel what it is like to be a bat, right?

Well, not really.

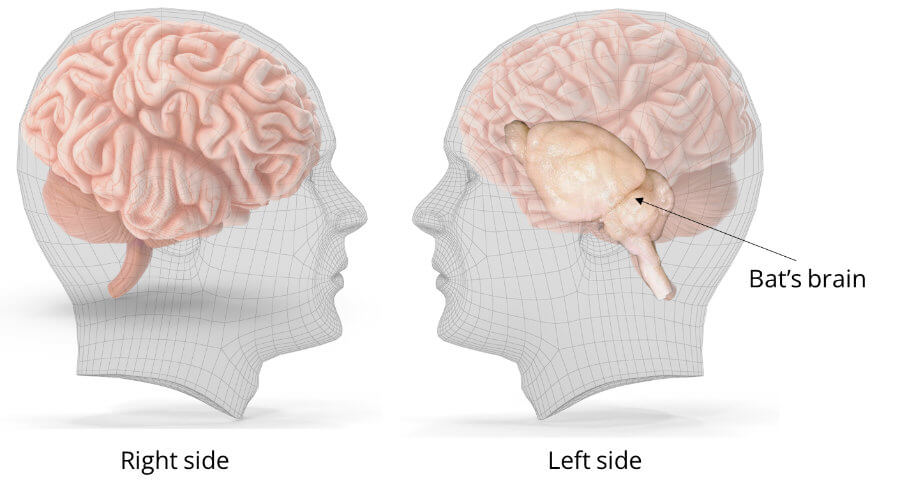

Clearly, your brain isn’t wired as a bat’s brain, so even if you were to be injected with the bat’s qualia, would you really experience things like a true bat?

First of all, wouldn’t we need the same neural machinery as the bat, in order to reproduce the bat’s qualia? If so, that would surely mean that our brains required a replica of the bat’s brain from which the qualia had been extracted.

Think of it like the difference between a cassette tape and a cd (see figure above). We can store the same music in both mediums, but we can never play the tape on a cd player. We might have an approximation of what the cassette tape might sound like on a cassette player (the frequency response, the distortions, the dynamic range, etc.), but we cannot really reproduce the exact same sound on the cd player. No matter how imperceptible to the human ear, there will always be minute changes during the conversion.

Likewise, even if we had access to the exact neural circuitry of a bat’s qualia down to the synaptic firing, without the bat’s neural apparatus it would be impossible to really feel like the bat.

Even if we ignore the hardware problem, would you be able to feel what it is like to be a bat, while still being aware that it is you who is experiencing the bat’s feelings? If you are not aware that you are you, would you have memories of what it was like to be a bat once you came back to your own self? If you didn’t have any memories of it, how would you know what it felt like to be a bat?

Let’s now consider a situation in which a mad scientist developed a medical procedure that could transplant a bat’s brain into a human, with the human’s and bat’s brains somehow connected to each other. Thus, one could experience what being a bat feels like, and also be conscious of that experience as a human.

Setting aside the creepiness of this scenario, Nagel would probably still argue that this isn’t the same as what the bat is feeling. Surely, the consciousness from the human brain interacts with the consciousness of the bat’s brain, a component which is not present in the original bat.

Thus, because you are adding extra sensorial elements to your experience (the brains must be connected somehow), it cannot be argued that you know what it really feels like to be a bat.

Not easy stuff, right?

Leave a comment

Add Your Recommendations

Popular Tags