This post is part of a larger deep dive

Curious about the role of psychopathy and the Oedipus Complex in The Cell? Check out The Cell Explained!

Or read the full The Cell article!

This post is part of a larger deep dive

Curious about the role of psychopathy and the Oedipus Complex in The Cell? Check out The Cell Explained!

Or read the full The Cell article!

In the 1940s British psychiatrist John Bowlby examined the first years of life of adolescents that had been detained due to delinquent behaviour.

He speculated that individuals that had suffered emotional deprivation in childhood would be at risk to exhibit delinquent behaviour.

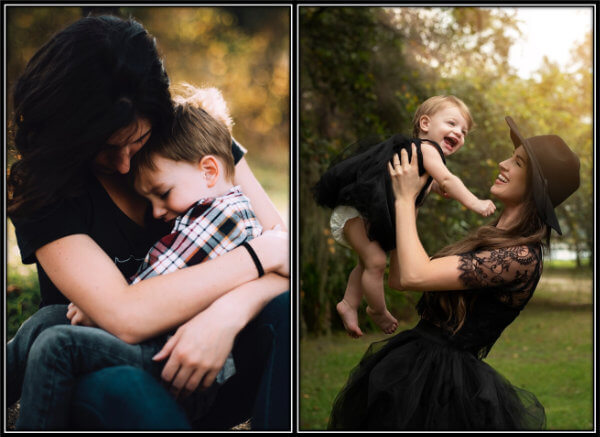

As with his predecessor Sigmund Freud, Bowlby believed that the way we interact with others was, first and foremost, influenced by those early years. Specifically, Bowlby suggested that children instinctively look for a primary caregiver (e.g., the mother, the father, a grandparent).

If the interactions with the primary caregiver are adequate, the child will develop a “secure base”, which is an important step in the development of the child’s personality. With a secure base, the child will learn to explore the surroundings and will start to socialise.

The secure base is developed during a very specific and critical period in childhood. If the primary caregiver is absent during this critical period, it is very unlikely that the child will succeed in developing the secure base.

Bowlby went on to conclude that delinquent behaviour was more common in children that had experienced maternal deprivation during the critical period, and thus lacked a secure base.

For example, Bowlby interviewed delinquent teenagers and observed that those that had had maternal deprivation showed more signs of psychopathy (e.g., inability to experience guilt, lack of remorse for criminal behaviour, lack of empathy for their victims).

Based on Bowlby’s models, development psychologist Mary Ainsworth devised a very clever experiment (the Strange Situation) that for decades has become the basis for assessing the quality of a child’s attachment to their caregiver.

The experimental procedure goes like this (see also video above):

1) infants (1-2 year old) play in the experimental room while their caregiver passively watches.

2) a stranger comes into the room and interacts with both the caregiver and then the infant. The caregiver then leaves the room, leaving the infant alone with the stranger.

3) After a couple of minutes the caregiver comes back in the experimental room.

4) The stranger and caregiver then both leave the room, leaving the infant alone.

5) The stranger then enters the room. A few minutes later, the caregiver also enters the room and picks the infant up.

6) The stranger then leaves the room, leaving the infant alone with his/her caregiver.

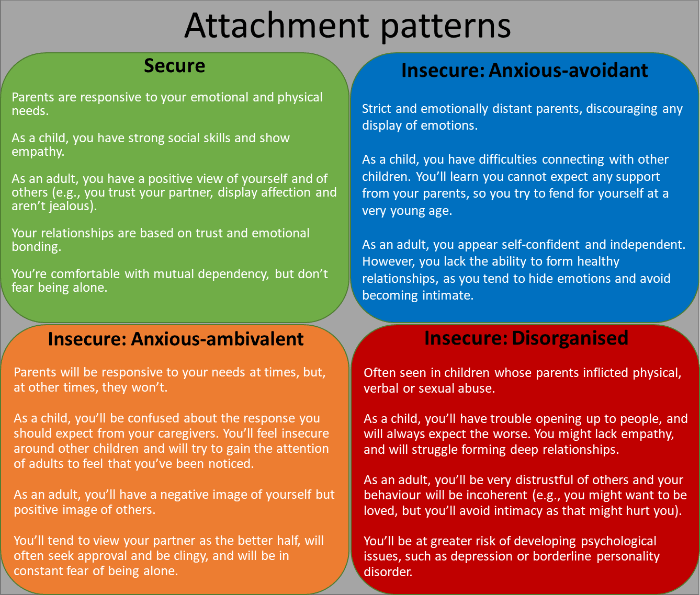

Ainsworth reported four broad distinct styles of attachment, depending on how the infant reacted to each of these situations:

Secure

Infants in this category explored the room when the parent was around and even interacted with the stranger, using the parent as a secure base. When left alone, they got slightly, but not overly, upset. They quickly got comforted as soon as the parent returned and resumed their playing.

Insecure: Anxious-avoidant

Infants with an avoidant pattern didn’t care much whether either the parent or the stranger were in the room or when either left. There was virtually no exploration regardless of who was present in the room. The children were unemotional for the most part and did not show separation anxiety when the caregiver left. They also did not seek comfort when the caregiver returned.

Insecure: Anxious-ambivalent

Here, infants stayed around their parent and did not explore the room much. They were clingy and exhibited anxiety even before the caregiver left the room. When the parent left, they threw a tantrum and upon the parent’s return, the children reacted with anger and refused to continue playing.

Insecure: Disorganised

Here, the infants weren’t very responsive and/or engaging. They tended to fluctuate between extreme avoidance and outbursts of emotion. They also looked confused and disoriented upon the caregiver’s return.

In general, there is a consensus in the attachment literature that being affectionate towards the child (e.g., playing with them, comforting them when they cry, giving them food when hungry, etc) will most likely lead to a secure attachment.

However, if the parent abuses or neglects the child this can lead to an insecure attachment as the child feels he/she cannot depend on his/her parent.

For example, children with a disorganised attachement pattern become anxious of the people that they are looking for protection, hence will often appear confused. The child will also be in constant fear, avoiding most social situations.

In the most severe cases, in which the child is very unresponsive and/or shows extreme sadness or fear during the experiment, it could indicate that the infant is at greater risk of developing a condition called Reactive Attachment Disorder. The child will be unable to form a healthy relationship with the primary caregiver, and will have an increase chance of becoming violent, abusive and cold-hearted towards others.

Worryingly, some research also found associations between insecure types of attachment (particularly avoidant/anxious) with psychosis development.

Psychologist Peter Fogany put forth a theory based on the concept of mentalization that attempts to explain, among other things, the behaviour of psychopathic individuals.

Mentalizing is the ability to think about what goes on in other people’s minds so that we can understand their behaviour.

Of course, we cannot know what others are thinking, feeling and wishing. However, we can infer what they are thinking, feeling and wishing from the way they behave and talk (e.g., if we see a child holding a broken toy and crying, we can infer that they are sad and want to have the toy repaired).

This comes in handy in social contexts, because mentalizing allows us to predict the response of others, which will be decisive in forming relationships (e.g., by promoting cooperation and avoiding conflict).

Fogany hypothesised that our ability to understand others is very much shaped by how our own mental states have been understood during childhood.

If the primary caregiver has had an adequate emotional response to the needs of the child, the child will have been able to register that his/her own feelings had been understood. The caregiver should thus transmit his/her mental states to the child, so that the child learns how this kind of communication takes place.

However, when children are physically abused, the ability to mentalize is seriously compromised. Adopting the perspective of the aggressor (the caregiver) would bring more pain, so children experiencing maltreatment simply do not learn to reflect upon what goes on in other people’s minds. These children tend to grow up and become impulsive and lacking empathy (what Fonagy refers to as “pre-mentalizing modes”).

Fonagy and colleagues demonstrated that most prisoners that had been incarcerated due to violent crimes came from a deficient family environment. Importantly, the research team also showed that these prisoners had a decrease ability to mentalize, that is, they failed to understand the mental state of their victims.

So, violent criminals tend to reject individuals and institutions as possible objects of affection. They seem unable to put themselves in other peoples’ shoes and fail to understand the serious psychological harm they inflict on their victims.

In one well-known study from the University of Cambridge, a research team analysed a series of variables and their relationship to delinquency, such as low IQ and school failure, child maltreatment, parental conflicts, size of family, etc.

For example, it was observed that about 40% of delinquents experienced maltreatment by one of the parents, with implicit consent from the other. They also showed that the probability of children becoming delinquents later in life increased if the child had little to no affection from any of the parents. Furthermore, having delinquent parents increased the chances that their children would also be delinquent and would commit similar crimes to those committed by their parents.

Very solid analysis!! I’m a clinical mental health therapist and I was looking for a good clinical breakdown of this movie. This one did not disappoint. Your analysis was thorough and spot on. ❤

Hi Aliya,

Thank you very much for your comment!

Given that you are a mental health therapist, I would be very curious to hear your opinion on how clinical practitioners would even approach a case like that of Carl Stargher (provided he sought help in the first place, of course)? His case seems so extreme that I wonder how current therapies would be prepared to dealing with such cases. Any thoughts?