This post is part of a larger deep dive

Curious about the role of the Spanish Civil War and "The Consequences of War" by Peter Paul Rubens in Guernica? Check out Guernica Explained!

Or read the full Guernica article!

This post is part of a larger deep dive

Curious about the role of the Spanish Civil War and "The Consequences of War" by Peter Paul Rubens in Guernica? Check out Guernica Explained!

Or read the full Guernica article!

After the World War I, Spain was a deeply polarised country. Opposition to the monarchy grew stronger after a series of debacles that saw King Alphonso losing the majority support of his army. The financial gap between the wealthy and the middle class also began to widen by the day, drawing both social classes to political extremist ideas.

In 1931 local elections were held that saw the opposition party, the Republicans – a conglomerate of political movements including communists, socialists, anarchists and syndicalists (all very anti-monarchy) – victorious. As a result the King was sent into exile, and a democratic republic was declared.

Although many reforms were initially planned, they were controversial and slow to put to practice, which alienated both the left and right. Several strikes erupted across Spain, eventually cracking down the government. At the General Elections of 1933, CEDA, a Catholic conservative political party with fascist ideologies, won the majority of the seats.

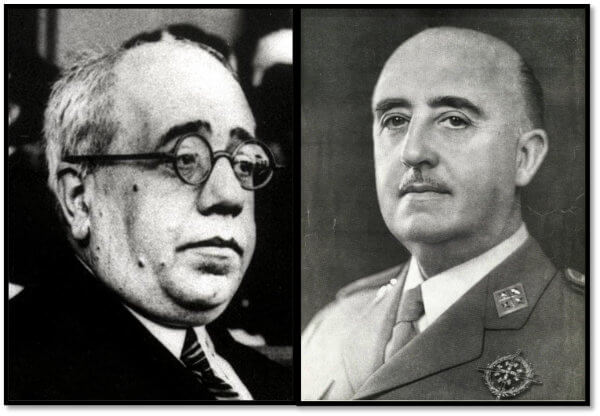

Unhappy with the prospect of a conservative regime in power far-left political factions rose up and took over the province Asturias by force. As a response, the army sent a loyal monarchist general called Francisco Franco, to quell the revolution, which he did with appalling brutality.

The left-wing parties realised that the only way to regain power and defeat the far-right would be to cooperate. And so they formed a coalition, the Popular Front, which stood against CEDA at the General Elections of 1936. The Popular Front won narrowly.

Fearing that the land would plunge into communism, a far-right military faction within the Spanish army launched a coup shortly after the elections.

Mutiny first erupted in Spain’s colony in Morocco. Franco joined them and formed the Nationalist movement – a movement which, he believed, would save Spain from the threat of communism.

But there Franco faced a problem: in order to get the fearsome army of Africa to mainland Spain, he would need to cross the strait of Gilbratar, which, at the time, was controlled by the Republicans-sided navy.

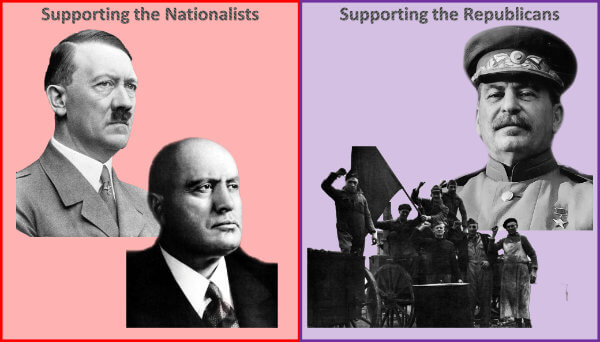

So Franco decided to ask for help from Adolph Hitler and Benito Mussolini. And both agreed.

Hitler’s decision to get involved in Spain’s war and side with the Nationalists was largely motivated by the prospect of having a state friendly to Nazi-Germany and, at the same time, inimical to France. Also, this involvement would provide a distraction from German rearmament, as well as a testing ground for Germany’s latest military technology and fighting tactics.

And so, Hitler sent Luftwaffe airplanes, tanks and thousands of troops to Spain. Mussolini, in turn, sent about 50.000 men and hundreds of aircraft.

Once Franco and his army of Africa arrived in continental Spain, the Nationalists immediately began pushing north towards Madrid. The advance was particularly fierce – a sort of Iberian blitzkrieg. With the help of their German and Italian allies, the ruthless and extremely disciplined army of Africa pushed through connecting the southern with the northern front.

The Republicans turned to Britain, France and the Soviet Union, which, fearing that their intervention would initiate an European war, declared a policy of non-intervention. Both Gemany and Italy also agreed to this policy, but blatantly ignored it.

The leader of the Soviet Union, Joseph Stalin, realising that Germany ignored the pact, decided to help the Republicans by providing tanks and fighter aircraft along with miliaray advisors. Not out of kindness, one must say. In fact, Stalin saw it rather advantagous to have a communist-friendly country in Europe. In addition, a Spanish war would keep Germany and Italy occupied, which would give Stalin precious time to build Soviet Union’s own military strength.

The Republicans also counted with the help of thousands of left-wing British, French, German and American volunteers (the so-called International Brigades).

However, the number of volunteers fighting for the Republicans was modest compared to the assistance Franco had received. As brave as the Republicans were, most volunteers were under-equipped and lacked proper military training. They were no match for the professional soldiers under the leadership of Franco (particularly the disciplined army of Africa), as well as the ultra-modern weaponry provided by Germany and Italy.

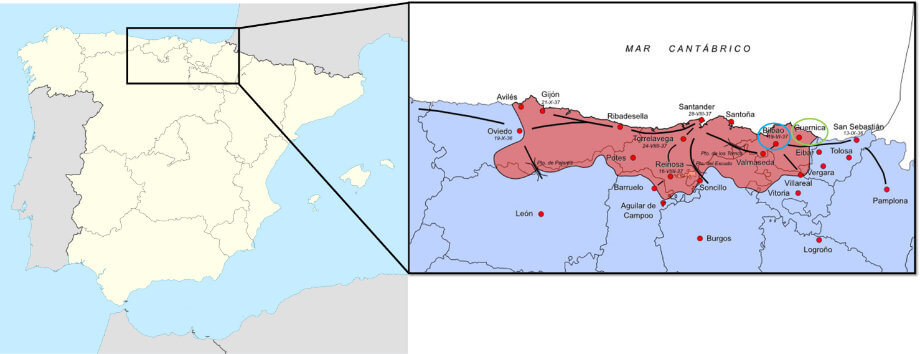

After seizing key cities in southern Spain, Franco and his Nationalist troops concentrated their efforts on the northern front.

Even though northern Spain was mostly under the control of the Nationalists, the Basque country, which included the city of Bilbao (a major industrial centre in Spain), was still under Republican control. The Nationalists believed that taking over the city would put a quick end to the war in northern Spain, and potentially decide the course of the war.

Guernica, a small village of 7000 inhabitants and only 30 kilometers from Bilbao, was what stood between the Nationalist advance and the capture of Bilbao. In addition, Guernica served as a retreat point for Republicans fleeing, and was the location of a weapons factory.

By this time, Germany had reorganised its existing military units in Spain, and formed a new legion called the Condor Legion, which consisted of modern bombers and fighters. In April 1937, under Franco’s orders, the Condor Legion as well as Italian bombers were deployed to Guernica.

The attack on Guernica was gruesome. Prior to the attack, bridges and roads had been completely destroyed to restrict the movement of Republican troops, and effectively lock everyone inside the town.

The Condor Legion employed a combined tactic involving both explosive and incendiary bombs, as well as indiscriminate machine gunning of unarmed civilians.

Over 3000 bombs were dropped on the town, which resulted in the destruction of about 75% of the buildings. Although estimates vary, it is believed that about 200-300 people were killed on that day, and many more were severely wounded. Most victims were children and women, since men were away fighting for the Republicans.

The defender’s morale dropped to its lowest, and any will to resist was crushed. Nationalists had no trouble taking complete control of the town.

A few months after the bombing of Guernica, Bilbao fell to the Nationalists, paving the way for Franco’s victory over the Republicans and complete domination of the country.

Only with a simply contrast b/w lenguage, that a child can easily undrestand, if you are a human(not you in this case).

With primeval figures in their desperation and most dramatic moments in their life and dead.

Almost like graffiti artists do in the same size today.

He brings us “The Horror of War”, but he is also warning to us.

A different war is coming.

The Spanish Civil War was reported by important journalists of the time.

This picture alerted and made the world aware of the pain and suffering that this new type of war brought with it, the so-called aerial bombardment of the civilian population.

Europe will experience it later in World War II.

For the painter it was a way of giving voice to his people and his message.

The press of those years was in b/w and the cinema too, except for some blockbusters with a very high budget.

In order to spread and raise funds for the Republican side (Defenders of democracy), against the Nationals (Franco dictatorship).

He presented his work at the Universal Exhibition in Paris in 1937.

Obtaining recognition and impact at a global level.

Those pioneers of graphic journalism of the time, in a photograph of the painting in b/w or without color.

They managed to convey the message of the painting to their readers, and after the passing of the years, it still retains the strength of its original genesis.

Whoever you are and regardless of who you are.

Thanks for your comment Cris! I think you have nicely summarised Picasso’s intentions with Guernica and the impact it had on the audience with this comment.

I admit I could have given more focus on Picasso’s sentiment towards the war, which naturally needs to be taken into account in any analysis of Guernica. I mentioned it in passing at the end of the Review section, but I should have probably elaborated on it.

I fully acknowledge Guernica’s potentiality as an anti-war symbol and this, by itself, is noteworthy; it is in fact one of the aspects of the painting that fascinates me. Unfortunately, reviewing the work as a whole, I do not think the quality of the painting is on par with the message it embodies.

lacklustre?

Inspired to inspire your deadclock imagine

Hi Cris. Yes, perhaps “lacklustre” was a poor choice of a word. But I was refering to the visual elements of the mural. To me, they simply don’t do justice to the intrinsic message of the painting, which I find profound.

However, art is subjective, and my opinion is really just that, an opinion. I tend to lean more towards classical art than abstract/cubist art, and my article likely reflects this inclination.