This post is part of a larger deep dive

Curious about the role of Freud's theory of the psyche in The Anthropomorphic Cabinet? Check out The Anthropomorphic Cabinet Explained!

Or read the full The Anthropomorphic Cabinet article!

This post is part of a larger deep dive

Curious about the role of Freud's theory of the psyche in The Anthropomorphic Cabinet? Check out The Anthropomorphic Cabinet Explained!

Or read the full The Anthropomorphic Cabinet article!

Way back in ancient Greece, Greek philosophers saw Man as a “rational animal” above anything else. Humans, they believed, did not base their actions on basic instincts like “lower” animals. On the contrary, humans could steer their own actions at will to whatever aim they felt more convenient, and were never under the dominion of our most archaic impulses.

Even though some philosophers did acknowledge that humans possessed obscure wishes that could, at times, cloud our judgements, they more or less agreed that humans could combat these less noble desires with reason.

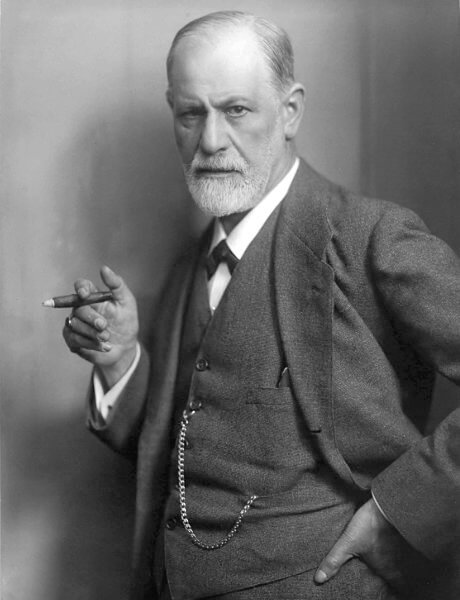

And so was the thought for the next 2500 years or so, until Mr Freud came into the picture and dropped a bombshell.

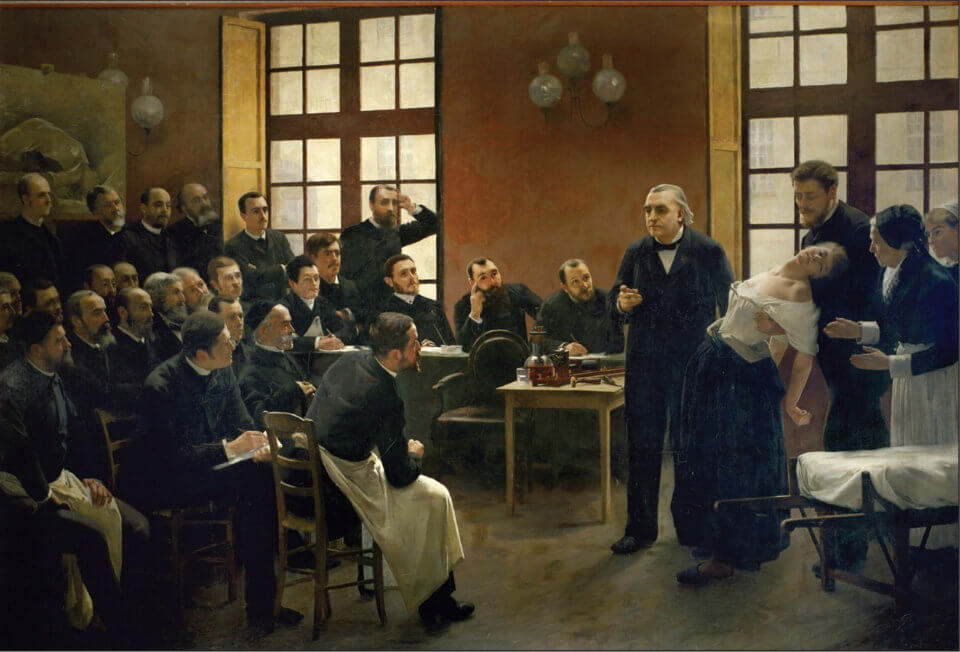

Freud studied and practiced medicine in Vienna, where, as I mentioned earlier, he founded Psychoanalysis. By examining both patients with a multitude of psychopathologies, as well as performing auto-analysis on himself, Freud concluded that humans’ seemingly rational behaviour was governed by an unconscious force – the libido, or sexual drive.

Uh-oh! If you do not immediately see the implications of this idea, Freud was essentially arguing that there was no real free-will. We were basically slaves of our most primitive, basic instincts that molded our decisions and actions, without us ever being aware of this influence!

As you might imagine, the puritanical society of late 19th Century/beginning 20th Century Vienna pretty much deprecated much of Freud’s ideas. Freud gained a considerable amount of opposition from the scientific community, and it was not long before his theories became a topic of ridicule.

Nevertheless, Freud’s determination did not falter and after some turbulent times he went on to become one of the most important figures of the 20th century.

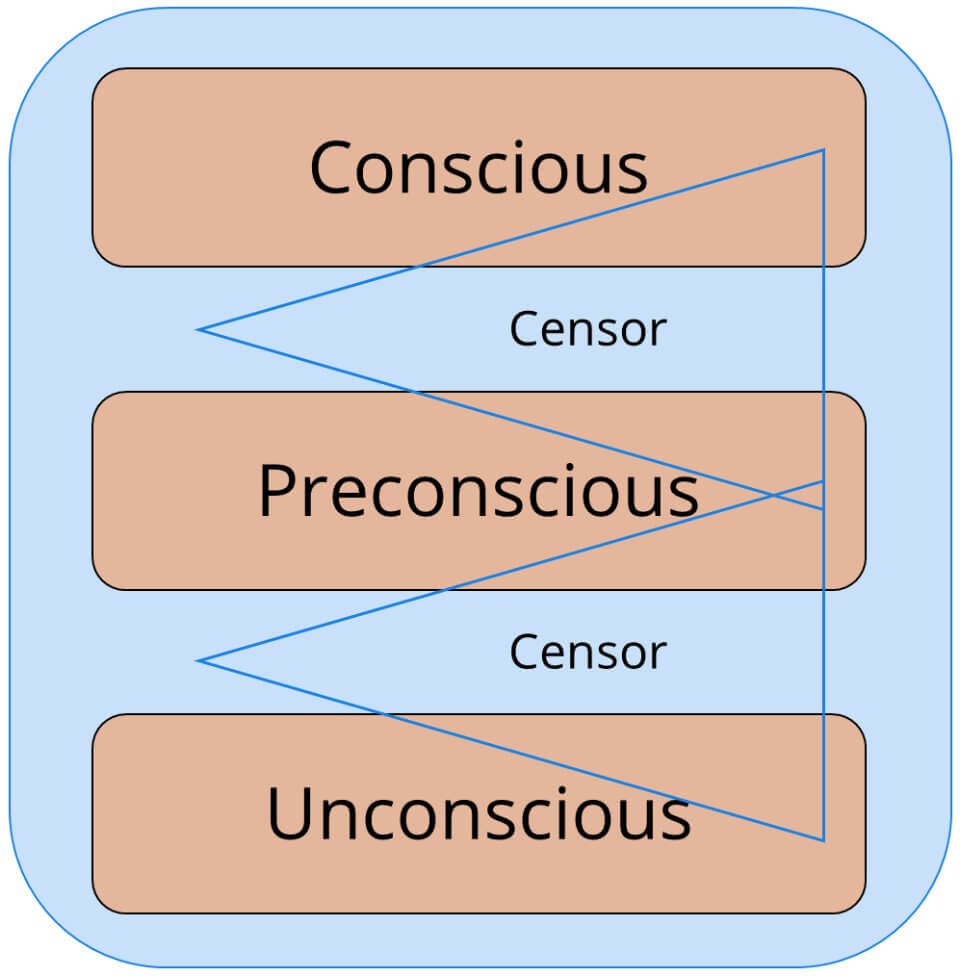

In his earlier work, Freud asserted that the human mind was compartementalised into a conscious, a preconscious and an unconscious “compartment”. These compartments, he went on, didn’t reside in physical brain regions, but were rather thought of as a representation of humans’ mental activity.

The Conscious mind was the place where your conscious thoughts were located. When you think I’m hungry; I am tired; I am a great supine protoplasmic invertebrate jelly – this is your conscious mind at work. Consciousness was therefore the part of your mind through which you interacted with others and the world at large.

The Unconscious mind, on the other hand, was where problematic and repressed thoughts or memories resided. For example, certain traumatic and painful memories (e.g., war atrocities, sexual abuse), or wishes that caused extreme embarrassment were all locked up in the Unconscious.

The Preconscious was kind of a middle ground. Things here could go either way – they could become conscious or unconscious, depending on the current situation and their emotional significance. For example, a recent event (e.g., hearing Dogtanian’s intro song) might trigger the memory of a mild emotional experience that had occurred in your youth (e.g., remembering once having spilled soda over your shorts while watching Dogtanian). So, that memory, which had been previously stored in the Preconscious, surfaced to the conscious mind.

How did the mind decide whether a memory should be promoted to Consciousness or demoted to the Unconscious?

For that task, Freud argued that there was a censor that served as a kind of psychic gatekeeper, deciding what contents to release to the other regions of the psyche.

In fact, Freud speculated that there were two instances of this censor: one situated between the Unconscious and the Preconscious, and another located between the Preconscious and the Conscious.

There was a good reason for the existence of this censor. Freud believed that once suppressed material loomed in the unconscious, it could not be accessed directly, as the censor would prevent most unconscious material to become conscious. It did this in order to prevent traumatic and painful content to have a negative effect on the person. However, if the memory was only slightly emotional, and perhaps even helpful, the censor would relax its grip on the memory and allow it to reach consciousness.

As Freud matured his theories, he became adamant that psychopathologies were the result of some internal conflict that had occurred sometime in the patient’s past. Due to their disconcerting content, the mind chose to bury it in the Unconscious, and stationed a vigilant censor to bar passage of this material to other parts of the psyche.

However, he viewed traumatic/embarassing memories and wishes as persistent, with the sole aim to ascend to consciousness. In order to escape censor’s constant surveillance, these repressed memories/wishes would appear camouflaged as symptoms.

That was the reason, according to Freud, why patients with numerours psychopathologies tended to exhibit such strange behaviour (e.g., emotional lability) – these symptoms were repressed memories, thoughts and/or ideas that surfaced under disguise.

It may not be obvious at first, but digging enough into the patient’s past and via a series of (at times, convoluted) associations, a talented Psychoanalyst would eventually be able to uncover the root of the conflict.

The stratification of the psyche into a Conscious, Preconscious, Unconscious and censor was developed as part of Freud’s first topic (topic comes from the Greek word topos, which means location. With it, Freud possibly intended to depict a map of the different locations that inhabit our psyche).

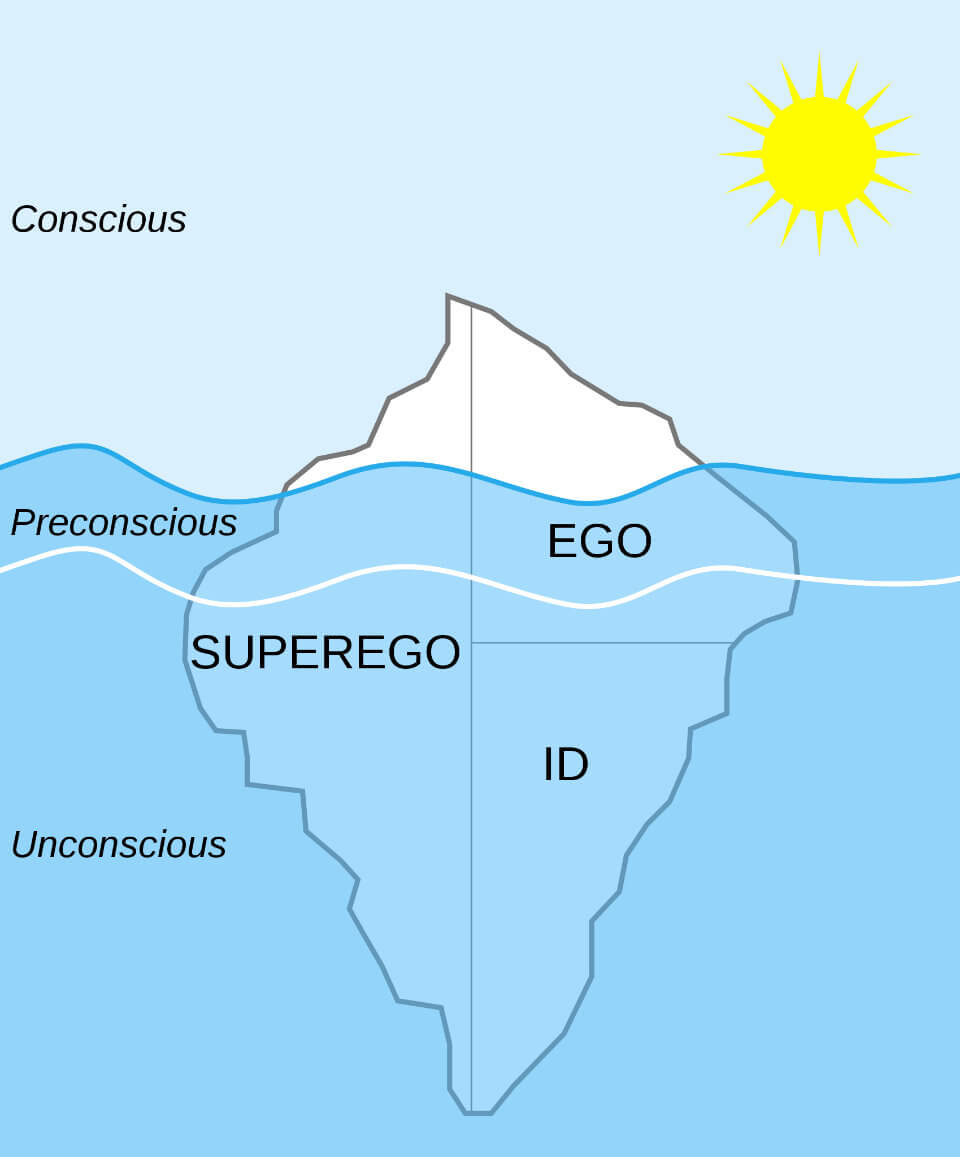

However, the first topic is by no means definite. Freud reviewed and expanded his theories over time and his second topic (which you might know from the famous image of an iceberg representing the Ego, Id and Superego structures – see above) is seen, by most academics, Freud’s more important theoretical model regarding the study of the psyche.

The first topic will be enough to interpret “The Anthropomorphic Cabinet” (no worries, there will be plenty of opportunities to discuss the second topic in detail in later articles). Nevertheless, there is one aspect of the second topic which I would like to mention here as it is relevant for the discussion of the “The Anthropomorphic Cabinet”.

During the subsquent years after the formulation of the first topic, Freud concluded that the human nature obeyed primarily to sexual instincts stored in the Unconscious.

You read it right! Freud was claiming that most decisions people took in their daily lives were, in one way or another, influenced by sexual instincts that had been somehow repressed in the Unconscious.

This sexual energy was the reason for many symptoms seen in neurotic patients, as I described above, although it could also be channeled to more productive activities, such as a friendly relationship, an aritistic work, a job, etc.

Now, this is going to sound weird…

Not only was Freud claiming that our conscious behaviour was mostly influenced by these unconscious wishes of sexual nature, but that these wishes could be traced back to experiences in early childhood (you may have heard of the Oedipus complex, which is arguably the quintenssential of these experiences).

Enough said about this though, because the psychosexual development in early childhood is a whole other topic that requires a dedicated article.

Leave a comment

Add Your Recommendations

Popular Tags