Review

Flatland is a story narrated in the first-person perspective of a character called A Square (a literal square), after he had a glimpse of the third dimension.

The novella is split into two parts. In the first part, A Square explains to the reader the different aspects of living in his 2-D world that three-dimensional beings call Flatland: the different shapes that exist, the social hierarchy, particularly meaningful events that occurred, etc.

In the second part of the novella, A Square narrates his (mis-)adventures after a Sphere visits Flatland and takes A Square on a sightseeing tour of Spaceland, allowing A Square to gain an understanding of three-dimensional space.

I find the idea of Flatland spectacular. For a novel written in the late 1800s, Flatland seems impressively contemporary in its ideas and it has managed to remain relevant even to this day.

Indeed, plenty of films and TV shows have direct references to the novel. For example, in the film Interstellar (which is related to the concept of higher-dimensional space), Joseph Cooper accidentally drops the novel Flatland from a bookshelf. In the TV series The Big Bang Theory, Sheldon Cooper mentions that one of his favourite places to visit is Flatland from Abbott’s novel.

Abbott, who had graduated with the highest honors in mathematics, showed that he knew his business. His descriptions of places existing in lower dimensions were picked by the likes of Stephen Hawking and Carl Sagan, who took inspiration from Abbott’s novella and popularised the topic of extra dimensions.

Despite its potential, I do have a few criticisms.

First, the first part of the novella (which comprises half of the book) is purely descriptive of the inhabitants and the world they live in. There is no particular plot to speak of. Even the second section of the novella, which is certainly the most interesting of the two, suffers from an underdeveloped plot, with only sporadic and ephemeral entertaining passages.

Thus, even though I found the topic of dimensionality extremely interesting, it felt more like reading a textbook rather than a novella.

The writing style of the first section in particular was also quite difficult for me to get into. In all honesty, I learnt more about the topic from reading reviews of the book than from the book itself. That might sound unfair, given that we had more than 100 years to dissect Abbott’s novella and apply modern teaching tools to explain dimensionality.

Nevertheless, it could have been written in a more reader-friendly and exciting way, as some science fiction books from some of Abbott’s contemporaries (e.g., Jules Verne, H.G. Wells). Abbott’s descriptions were often convoluted and off-track, and I found myself losing interest quickly (although his explanations improved in the second section).

I did, however, find his drawings amusing, and they did help visualise the second dimension much more than the text descriptions were able to.

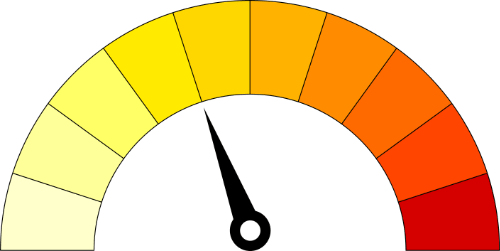

Star rating

I have to say that I have mixed feelings regarding Flatland.

On the one hand, the topic was great. Also, taking into account that the book was written at the end of the 19th century, I do think Abbott was reasonably good at simplifying a very complex topic to non-mathematicians (particularly his drawings).

However, the writing style and the descriptions of the first section were just not my cup of tee, and I think the book could have been improved to be a more interesting read.

Since Flatland is a novella, I was also expecting a relatively interesting plot. However, plot was almost inexistent, with most of the book devoted to explaining dimensionality. The most exciting event was A Square’s interactions with the Sphere, which really took up only two chapters.

Here at Mindlybiz, Flatland gets a rating of 2.5.

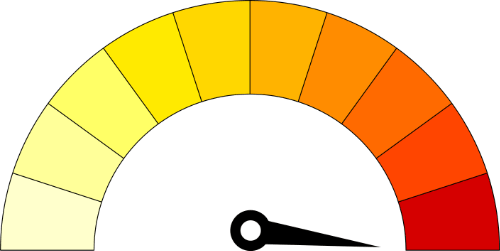

Bizarrometer

Hmmm… I would say Flatland is bizarre, not for the obvious reasons that the all characters are geometric figures (which is kind of weird on its own), but because the novella is highly satirical in tone.

Also, the topic of dimensionality is not an easy one to grasp, although I think the author did a relatively good job simplifying it to the general, non-mathematician reader.

Flatland gets a bizarrometer score of 2.

Masterpiece

Mind-blowingly weird

c’est bien..

thanks..

Hi,

Thank you for your comment, and I’m glad you enjoyed the article 🙂