Introduction

Being around like-minded communities which value the weird and the bizarre in art and entertainment above all, there was one particular novelist that cropped up almost all the time: Haruki Murakami. Never having heard of him, recommendations abounded. Apparently, virtually every book by Murakami appeared to tick all the boxes for inclusion in this website, with a lot of… talking cats. Huh?!?

That was already a red flag, but I decided to go along. People continued to warn me, “be prepared, it’s going to be really weird!”. I scoffed, thinking I’ve already lived long enough to have witnessed all kinds of bizarre. Right…

I decided to begin my Murakami’s initiation with arguably the most famous of his novels: Kafka on the Shore.

And people still persisted: “be careful, that one is especially weird!” Again, I scoffed “Look, I’m experienced, I like it weird. Some say, even insensitive to weirdness. Mr. Weirdo (that doesn’t sound good)”. And went on to read it.

…

Yep…

That was weird alright!

Review

Kafka on the Shore tells the story of 15-year-old boy Kafka Tamura, whose father prophesised that Kafka would kill him and sleep with his own mother and sister, both of whom left the family when Kafka was four years old. Kafka runs away from home to escape his emotionally abusive father. Along the way, he makes several acquaintances, two of whom Kafka believes may well be his long-lost mother and sister.

The story of Kafka alternates with that of Nakata, an elderly man who lost his ability to read, write, or recall past memories after a bizarre accident in his childhood. As a result of that accident, Nakata possesses the peculiar ability to communicate with cats. After a deadly encounter with an evil spirit, Nakata sets off on a strange journey that gradually begins to intertwine with Kafka’s.

Phew… Where do I start?

Maybe with this: Kafka on the Shore is a very dense novel, disguised as a light one.

Let me explain.

Overall, the book is a relatively easy read – clear language, manageable 10-page chapters, a mostly linear storyline. Major plot developments are few and far between. Most of the time, not much is happening, everyone is almost suspended in time, passively waiting for fate to intervene, as opposed to making things happen.

Thus, it isn’t unusual to have mundane descriptions such as Kafka’s routine at the gym, Oshima’s intellectual digressions on philosophy, or Hoshima’s introductory lessons in classical music.

In my opinion, these moments of stillness are very much human, relatable, and rooted in our everyday life experiences, which stand in stark contrast to some of the truly bizarre and brutal events in the novel.

The key moments in Kafka on the Shore are brought to you in the form of magical realism. The protagonists Kafka and Nakata are presented with ghostly apparitions and magical portals, without questioning their own sanity. As weird as these scenes may be, even they appear to be taken place in some kind of metaphysical otherworld, disconnected from physical reality.

So, why have I described the novel as being dense?

Well, despite Murakami’s literary prowess (note that I read the English translation, so I cannot speak for the original Japanese edition), the book will make your head spin like hell.

And not only because it contains really absurd and bizarre scenes. In fact, what I found harder to digest were the subtle connections between Kafka’s and Nakata’s storylines, since it’s obvious from very early on that the two are connected, when they shouldn’t be.

The two stories are told independently, with chapters alternating between Kafka’s and Nakata’s narratives. They pertain to characters that bear no relationship whatsoever with one another: Kafka and Nakata have different objectives in life, they are two generations apart, they never met, and there is no common lineage.

Plotwise, their connection makes even less sense: Kafka seems to be running away from his fate, whereas Nakata appears to be pursuing his; Kafka searches human connection, Nakata is indifferent to it; Kafka is young, energetic and curious, Nakata is old, unhurried, and resigned; Kafka thrives for knowledge, while Nakata is content with being simpleminded.

But it is exactly this polarity which interconnects the two stories – they are not separate, they complement each other! Kafka and Nakata are actually two sides of the same coin, but I’ll leave the details of what that means for a more thorough analysis of the book.

There is no shortage of symbolism in this work. Oedipus Complex is a major theme in the novel. This isn’t a spoiler by the way, it is there from the start. Kafka’s father prophesizing that Kafka will kill him and sleep with his mother is a literal take on the Greek tragedy Oedipus Rex (which influenced Freud’s psychoanalytical idea). The possibility of incest hunts Kafka throughout the novel, affecting his relationship with the women he encounters along his journey.

But don’t fool yourself thinking that Murakami settles with one theme throughout. Kafka on the Shore is incredibly layered; it reeks with symbolism and references to both Western and Eastern cultures abound. Greek tragedies, Japanese mythology, Classical/Jazz music, and even Cartesian mind-body duality are all themes that need to be considered when interpreting this novel.

The characters are well-developed, but they are not always consistent. Nakata was certainly one of the most endearing figures, as was Oshima’s protective and selfless behaviour. Kafka, on the other hand, struck me as the least believable: what kind of 15-year-old drinks milk instead of water, listens exclusively to Jazz, compulsively works out, reads heavy philosophical works, gets off with young and older woman alike, and behaves so calmly without the slightest hint of fear when convinced to be a murderer? It just felt there were too many traits crammed into one single character. Additionally, I felt the story lacked a stronger female presence, but sadly, this seems like a common bias in much of Japanese literature (see also our review of Paprika).

One particular aspect of the novel I also felt slightly out of place was the entire subplot involving cats. Apparently, cats are a recurrent motif in Murakami’s works. In Kafka on the Shore, Nakata possesses the peculiar ability to communicate with cats, and several scenes feature extensive bizarre dialogues between him and various feline characters. However, rather than having a deep symbolic significance, it seems the inclusion of cats in the story was purely based on Murakami’s fondness for them. Which is somewhat strange if you think about it, given the novel contains a very disturbing and gratuitous scene of cat torture.

And, since we are at it, don’t expect this book to offer a wide range of emotional tones. As emotions go, it’s really a one-way street. Kafka on the Shore leans heavily towards psychological drama with Lynchian vibes, so it’s unlikely to leave you with happy feelings. Kafka’s and Nakata’s journeys are ones of self-discovery and inner struggles: mostly confronting personal demons, coming to terms with feelings of loneliness, frustration and anger, and also learning how to accept and live with those feelings. There kinds of journeys are rarely pleasant, as they often demand us to face painful memories and/or unresolved issues.

And, in the end, isn’t that what we should all expect anyway? We often complain about sugar-coated stories, rolling our eyes at the overly exaggerated and unrealistic happily-ever-after endings. Well, that’s certainly not the case with this novel.

Kafka on the Shore’s ambiguous ending means that each and every one of us will reach a different conclusion, the significance of which will depend on how closely you relate to the characters. Maybe you identify with “Kafka” – dealing with the vicissitudes of a difficult upbringing. Maybe you identify with “Nakata” – feeling overwhelmed by the world at large and searching for a purpose in life. Maybe you identify with “Oshima” – living in the face of prejudice but still finding joy in small things (e.g., books, music, good conversations). Or maybe you relate with “Miss Saeki” – struggling with loss, resigned both to a life that feels empty and to people that feel alien to you.

And if I took anything from reading Kafka on the Shore, it was the realisation that a novel doesn’t need to explain every strange event or resolve every ambiguity. You see, by the end of the book I realised that asking whether this or that event was real was missing the point – what really matters is what those events mean to the characters. For example, Miss Saeki becomes the motherly figure Kafka needs in order to grow, regardless of whether she is his biological mother or not.

Kafka’s and Nakata’s stories are part of a personal and symbolic journey towards psychological integration. A journey that we all must take at some point. A journey across the psychological barrier that divides what we know about ourselves from what lurks in the shadows. A journey across the shore that divides our consciousness from our unconsciousness.

Star rating

Kafka on the Shore was my first novel by Murakami, and it made an interesting read. I particularly enjoyed the subtle connections among the different characters, as well the unsettling ambiguity surrounding them – Is Sakura Kafka’s sister? Is Miss Saeki Kafka’s biological mother? Are Nakata and Kafka the same person? I kept asking myself these questions during my reading of the novel, even though I knew pretty well I wouldn’t get a clear answer to any of them by the end of the book. In fact, I’m currently writing my deep-dive of Kafka of the Shore, and I can tell you that I’ve changed my mind like 5 times already regarding whether Miss Saeki could be Kafka’s biological mother!

Magical realism was not overdone, but done just right. The writing was exceptional and the mood always atmospheric.

Sadly, the book is short on excitement. Some of you will say it was never meant to be; that Kafka on the Shore is a symbolic and metaphysical work, a meditative and evocative essay on how to cope with loss, solitude and the challenges of coming of age.

Which is fine, but probably not to everyone’s taste. My feeling was that it lacked a steady narrative flow. The story lacks momentum, and I often found myself wanting to give it a little push in parts where the narrative felt like it had stalled. These moments of standstill may well have been intentional to create the mood Murakami intended. However, in my opinion, this decision backfired, as it frustrates the reader given that key developments are so sparse.

Don’t get me wrong, I did enjoy reading it, it just wasn’t as engaging as I hoped it would be.

Still, I believe that this novel should be essential reading for any surrealist lover, so, here at Mindlybiz, Kafka on the Shore gets a star rating of 3.5.

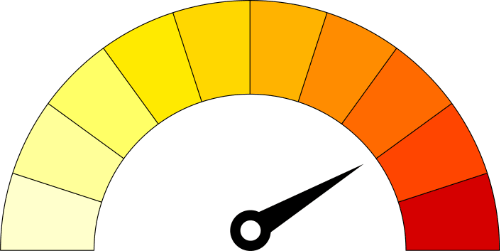

Bizarrometer

Kafka on the Shore is among one of the most bizarre books I have read, although still not the weirdest (can you guess which one that is?). Murakami’s excellent writing style means that readers won’t have difficulties to follow the story – whether they understand all aspects of it is a different matter – but the main plot isn’t hard to grasp.

But make no mistake, the novel is very weird. The defining feature of bizarreness is mostly the atmospheric mood, time standstills and strange occurrences like ghostly appearances, the odd animal rain, talking cats, and magical portals. The surreal cat torture scene was dispensable in my opinion, but I found the references to Western icons (e.g., Colonel Sanders, Johnnie Walker) snappy.

Unexplained events remain unexplained, enigmatic moments remain ambiguous, and, for those reasons, Kafka on the Shore receives a bizarrometer score of 4.

Leave a comment

Add Your Recommendations

Popular Tags