Introduction

I suspect that very soon a substantial portion of the content in Mindlybiz will have its origin in Japan. Why’s that, you may ask?

Well, I have watched countless Anime and read numerous Manga and Japanese novels that had some of the weirdest narratives I have ever encountered (and, unrealistic ambition aside, I plan to review them all!).

And it’s not like these kinds of Japanese fiction are simply weird without regard to a compelling narrative. Quite the contrary! I have found most of these works to be an ingenious mix of surrealism and deeply thought-provoking and original ideas.

It’s as though Japanese writers have a knack for creating psychological thrillers. Granted, not every work fits my liking: why the heck is this guy walking around with a paper bag on his head? But hey, to each his own, right?

Since my teenage years I have had a genuine interest in fictional works connected to the mysterious realm of dreams. The anime movie Paprika was recommended to me after watching the (also excellent) movie Inception.

However, being one of those people that always starts with the source, I decided to read the book which the film was based on. So, in this article I’ll be analysing Paprika, the novel by Yasutaka Tsutsui.

Review

The novel introduces us to the main character Atsuko Chiba, a beautiful researcher and psychotehrapist working at the Institute for Psychiatric Research in Tokyo, Japan.

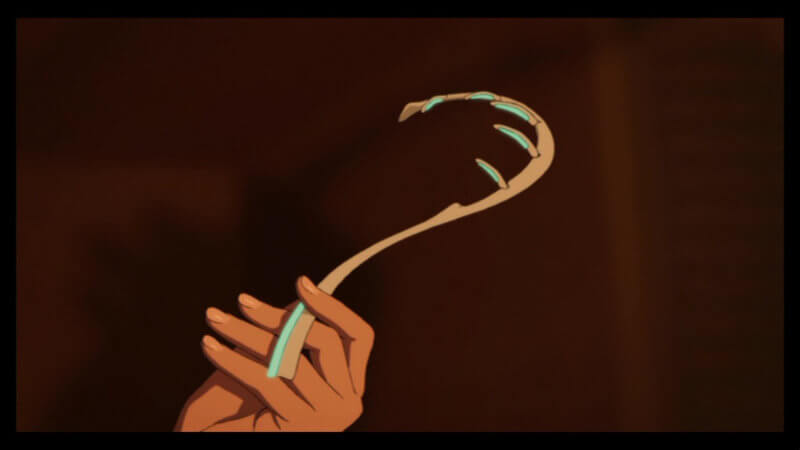

Her genius colleague and boyfriend Tokita has developed a portable psychotherapy device (the DC Mini) that allows therapists to infiltrate the dreams of patients, and, in the process, help them recover from their psychic ailments.

This technology is still being developed and lacks legislation. Because it is illegal to use, Atsuko treats her high-profile patients in her apartment, where some of the equipment is located. When meeting her patients, she puts on a few false freckles and a wig and calls herself “Paprika”.

Things soon start to go awry, however, after a series of the powerful dream-controller devices is stolen. She becomes aware that the technology is being used for nefarious purposes by two of her colleagues, who infiltrate the dreams of unsuspecting victims, wrecking their personalities.

Dreams and reality begin to merge with one another as a consequence of repeated use of the perilous technology, and Atsuko and her allies engage in a surreal endeavour to prevent the real world from falling apart.

Even though I had high expectations for this story, I must admit Paprika felt disappointing.

First of all, I find most characters over the top, and I can’t figure out if that was intended or not. For example, as Paprika, Atsuko invites her patients to come to her apartment where she scans their dreams. When they approach the door to her apartment, there is a metal nameplate fixed on the wall with the text Apt. 1604 CHIBA written in bold capitals.

Seriously?!?

So, Atsuko, who is allegedly one of the smartest scientists in the world (after all, she is nominated for the Nobel prize in Physiology or Medicine), runs an illegal research project in her apartment, which, by the way, is in the same building as her archenemy’s flat?

Even after she is under serious suspicion that she might be Paprika, she continues to bring patients into her flat. This is nothing but folly. Nowhere does Paprika attempt to explain why she is doing therapy in Atsuko’s flat; she appears to simply hope nobody will figure it out. Then later in the book she appears surprised when two of her patients realise that Paprika and Atsuko are one and the same person. Well, duh!

Atsuko’s method is also blatantly unethical. Although she claims that engaging in sex or flirting with her patients is a shortcut to their cure (!), she appears to do it for fun. For example, after treating Noda, she asks him to kiss her as she later tells her boss Shima, “[Paprika] didn’t go as far she did with you. But she did let him kiss her at the end. […] In reality, she found him rather attractive.” Did I forget to mention Noda is married with children, and Atsuko knows this?

Similarly, when she is about to have sex with Konokawa (another patient), she says “Never mind – this was just a dream. It would simply be one more secret to be shared between therapist and patient […]“. And then later adds that “She felt that this virtual sex act might be more immoral than a real sex act between a therapist and a patient who really loved each other […] Nevertheless, Paprika could continue her treatment based on erotic experiences without feeling too guilty about it. […] If Konokawa felt guilty about this method, she thought, she could always have sex with him properly after he was cured“.

Look, I wouldn’t consider these points flaws in the story if the character Atsuko had been portrayed as a rebellious psychotherapist with little scruples and integrity. But it was my impression that Atsuko was being depicted as a heroine, a virtuous scientist and respectable therapist, whose only concern is the well-fare of her patients. But, really, any actual psychotherapist would immediately demand her suspension at the knowledge of her work methods, let alone be nominated for a Nobel Prize.

Another implausible character is Atsuko’s boyfriend Tokita. Here we have a genius scientist that has been developing really sophisticated devices, but who, for a strange reason, is incapable of memorising a simple instruction: add protective code to prevent unauthorised access to the devices. Dude, a simple 6-digit pin code would do the trick!

Maybe I would understand if the memory lapse had occurred with the initial prototype. But after making 6 of them?! And he just leaves them lying around with no safe-proof mechanism? Also, one DC Mini had been missing for a long time (one that Atsuko had forgotten in her pocket!), and he didn’t remember to tell Atsuko that it was missing. No, it was necessary that all of them get stolen for him to bring it up. This just strikes me as completely absurd.

To be fair, Atsuko is well aware of this when she says that Tokita “was completely incapable of such meticulous afterthought”. That might have been an understatement!

Some sections of the book were also very uncomfortable to read. For example, Atsuko professes her love for Tokita but is apparently disgusted by his appearance, and has no compunction fooling around with her patients. She makes non-professional comments such as “Interesting people have interesting dreams. Dull people only have dull ones.”. Homossexuality is seen as something perverse: for example, the only two homosexual characters are coincidentally the villains of the story; Konakawa, a high-ranking police officer, comments about the homossexual relationship that “that’s disgusting”; when a female colleague makes flattering remarks about Atsuko’s appearance, Atsuko notes “feeling slightly embarrassed at such unfettered adoration by a member of her own sex“.

And I don’t even know where to start with the rape scene. Atsuko is violently attacked in her flat by one of her colleagues, but, in the end, he is unable to carry out the rape. However, Atsuko gets really annoyed with him, not because he tried to rape her, but because he didn’t actually consummate it! The attempted rape apparently got her horny and wanting to have sex! What?!?

Finally, I felt the organisation of the book left a lot to be desired. The first part of the book is almost detached from the second part, in which the most interesting events occur. Sure, the first part introduces the characters and sets the stage for the events in the second part. However, most of the dreams that Paprika analyses in the first part are completely tangential to the main plot and bear little importance to the novel as a whole.

One a more positive note, the written language was quite accessible (at least based on the English translation). Narratives involving dreams tend to get confusing very quickly and the jumbled up nature of the dream content has the potential to turn stories into a mishmash. I feared this in Paprika, but was happy to have been proven wrong. Certainly, I expected the dreams sequences to be very weird, but the descriptions of the dream imagery and the pace at which the dream narrative evolves is very adequate in my opinion.

I also enjoyed reading Paprika’s dream interpretations of the unquestionably complex dream narratives of her patients. You can tell the author did some research, and although I found Paprika’s psychotherapy unlikely (e.g., the dream theories of Freud and Jung are antithetical, but Paprika appears to endorse both of them), her interpretations were fun to read.

Our rating

The concept of Paprika is a clever one. I do see the potential of the story and definitely congratulate the author for his fascinating imagination.

However, as outlined above, I found the book had serious flaws (e.g., incoherent characters, poor book organisation) which diminished my enthusiasm for the book. Here at Mindlybiz, Paprika gets a rating of 2 stars.

Bizarrometer

This is a tough one. The novel is divided into two parts. The first part is very accessible – there is a clear separation between the dream world and reality, which makes the story easy to follow. In part, that is due to Atsuko’s interesting therapy dynamics, interpreting dreams with her patients.

The second part of the book, however, begins to entangle dream and reality, producing a more confusing storyline. Nevertheless, the reader is never left completely lost and the author was careful to explain most dream-reality transitions as the novel progressed. Paprika gets a Bizarometer score of 3.

Paprika (briefly) Explained!

In its core, Paprika isn’t a particularly difficult story to analyse. All the ingredients for a good-guy-bad-guy sort of narrative are present.

On the one side, we have the heroine of the story, Atsuko/Paprika, with her unmatched beauty and wits; the representation of virtue, bravery and progressive views.

On the other side, we have Inui, a cantankerous old man, pestered by envy of Atsuko’s success. His sole intent is to discredit her and restore the conservative values of psychotherapy. He represents conformism and hidebound thinking.

Supposedly, one could interpret this divergence as a religious battle. The book makes it clear that Inui is a fervent Christian. A passage in the book, for example, reads that “[…] whenever he [Inui] treated Osanai with tender affection, he himself had come to resemble Jesus. He had even started to see himself as the savior of the psychiatric world“. When Paprika is about to depart to Sweden, Inui announces “The host of Christ, assembled on the plain of Jerusalem, declares war on the host of Lucifer on the plain of babylon“. Inui even chose a cathedral with the figure of Christ as the place for the last confrontation.

In contrast, during the Nobel Prize ceremony, a griffin begins to attack Paprika and Tokita, but Vairocana (the incarnation of Buddha) and Acala (the protector of Buddhism) materialise to save them – the two Buddhist images were none other than Kuga and Jinnai, respectively, the two bartenders of Radio Club and Paprika’s allies. Interestingly, there are several mentions of Kuga resembling Buddha, and it is Kuga who, unexpectedly, pretty much saves the day (see below). So, does this mean a victory of Buddhism over Christianity?

The first part of the novel introduces the reader to all relevant characters, as well as to the robbery of the newly developed DC Mini technology that plunges Paprika and her friends into a fierce battle for dream control.

Paprika and allies realise that the more the DC Mini is used, the more it pushes its users into a deeper and deeper sleep. Reality and dreamworld begin to conflate, putting sleepers at a serious risk of never waking up.

Mind-reading, teleportation of dream characters and objects into reality, and even time-travel are all side-effects that spontaneously emerge due to repeated use of the DC Mini.

Ultimately, it all boils down to who has the upper hand in controlling these side effects.

Although the battle between Paprika and Inui remains initially balanced, Inui’s power gradually increases as a result of his ever deeper sleep, and, consequently, giving him greater control over dreams.

By the end of the book, when nothing seems to put a stop to Inui’s dream turmoil, the battle unexpectedly ends, as Inui’s dream control wanes. Inui appeared to have been sleeping for days and days, eventually starving to death.

Because dream imagery disappears as soon as the dreamer wakes up (or dies), Kuga takes the opportunity to reset time and bring everyone to a not-so-distant past.

The book ends with a very cryptic chapter involving the two bartenders of Radio Club, leaving ambiguity regarding what was the dream and what was reality.

Before I expound on these points, I’ll describe some interesting facts about sleep and dreams.

Leave a comment

Add Your Recommendations

Popular Tags