This post is comprised of different sections

Take a look at our review of Dogville!

Learn more about Stoicism and Nietzsche's philosophy of the future!

This post is comprised of different sections

Take a look at our review of Dogville!

Learn more about Stoicism and Nietzsche's philosophy of the future!

Director: Lars von Trier

Producer: Vibeke Windeløv

Writer: Lars von Trier

Starring: Nicole Kidman, Paul Bettany, Lauren Bacall, Stellan Skarsgård, James Caan

Year: 2003

Duration: 2h 58m

Country: Sweden, Denmark, United Kingdom, France

Language: English

Our rating

Your rating

There are a few directors whose films I always insist to watch. Lars von Trier is one of them.

But I never, ever watch a Lars von Trier film without properly preparing myself that it is going to be an unconventional experience. Dogville was, indeed, no exception.

Having watched other von Trier’s atypical films such as “The Idiots”, “Europa” and “Dancer in the Dark”, I was sure Dogville would also be one of a kind. The question was: what kind?

The first time I watched Dogville was in the cinema, and after literally a few minutes into the film, I spotted people leaving the cinema room.

As for myself, I remained seated. You see, I seem incapable of not finishing a film, regardless of how scared, bored or tired I am (I’m lying, I actually left the cinema once towards the end of Spice World, but can you really blame me?).

So, yes, thanks to this admittedly slightly obsessive behaviour, I stayed until the end.

And I was so glad I did!

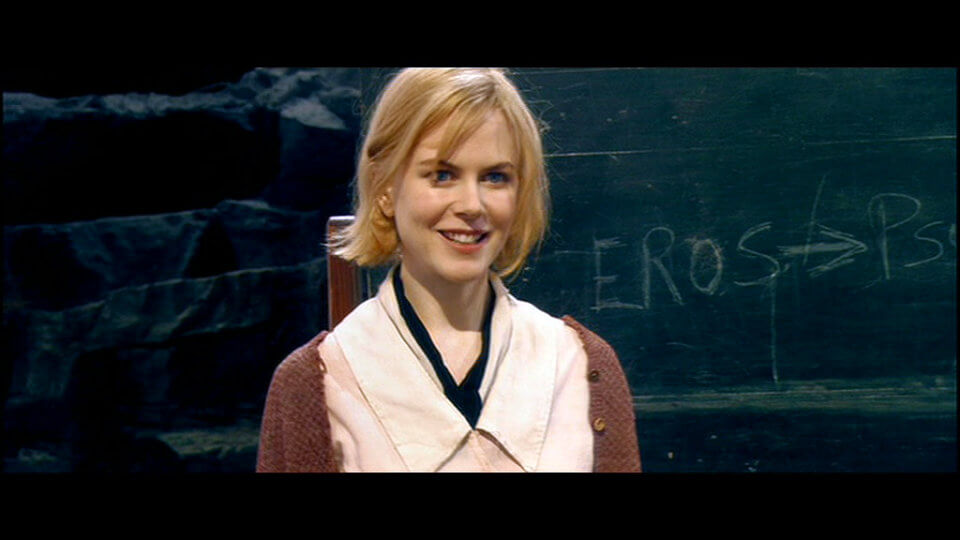

The film stars Nicole Kidman in the role of Grace Mulligan, a gentle and kind young lady that arrives at a little town called Dogville.

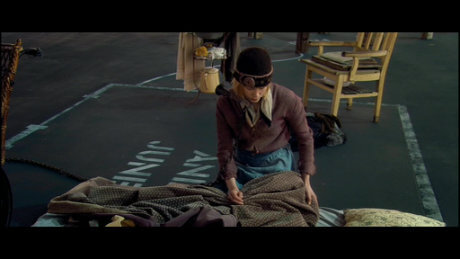

Dogville’s residents learn that she on the run from gangsters, so they become reluctant to let her stay, although they eventually agree. As time passes she starts to gain the townspeople’s trust and becomes central in helping the community to prosper by doing all sorts of little, but useful, chores.

However, Grace begins to notice a darker side to this town, as she becomes subjected to maltreatment by the townsfolk.

As with most von Trier’s films, Dogville gradually builds tension, which is released in a dramatic and twisted finale.

Despite it’s length (the film is almost 3 hours long) and somewhat invariable storyline, Dogville had myself gripped to the screen from beginning to end.

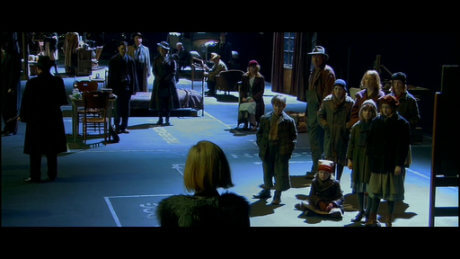

Most critics will surely point to the austere setting as a weakness – for example, the building walls and some objects are only marked by chalk; there is only a black/white background; and the whole film takes place in a single minimalistic set. It feels a bit like you are watching an eerie theater piece, the film is even divided by “chapters”, much like in theatre.

However, I do not consider it a weakness. In fact, as I’ll explain below, there might have been a reason why Lars von Trier chose this kind of minimalistic set.

And that last chapter, what an ending!!! The conversation between Grace and her father about morality must certainly rank among one of the best dialogues in the history of cinema – and, incidentally, the reason we are reviewing the film. How ingenious it was of von Trier to bring this scene up at a point when viewers are becoming exasperated by Grace’s passivity – it almost acts as a cathartic experience for the viewers.

One criticism I have is that, for a film of almost 3 hours, I would have welcomed more insightful philosophical discussions among the characters. The film starts slowly and at certain points I found it repetitive.

It would have also been interesting to explore the different characters’ perspective on questions of acceptance and morality. Although these ideas are briefly brushed over, they are hardly contextualised (for example, Tom’s idea of moral re-armament, or Grace’s understanding of Stoicism).

Dogville had probably many chances to have failed. I do not doubt that with a less provocative, experienced, and outright courageous director, it probably would have.

However, in my opinion, Lars von Trier ranks among one of the best directors and writers out there. Dogville shows his acumen to mingle philosophical ideas with real societal issues, and it does so in an unprecedented manner.

He managed to write a captivating story, a meaningful script, with fleshed out characters, and all that while remaining on a relatively low budget. For that reason, Dogville gets a star rating of 4.

OK, some of you might consider the film strange, definitely unconventional.

However, the narrative of the film isn’t really that weird. Everyone will be able to follow the storyline without major problems.

Yes, there are a few strange elements, like chalk-painted house perimeters with no walls, but these elements do not affect our understanding of the narrative. For these reasons, we give the film a 1.5 in the Bizarrometer score.

While reading around a few interpretations, I noticed that many interpretations revolved around the idea that the film somehow contained anti-American messages, which sparkled a fiery debate in social media.

Critics have referred to the credits sequence montage showing photographs of destitute Americans going as back as the 1930’s until the present day, while David Bowie’s song “Young Americans” is played in the background.

Without wishing to raise any hackles, evaluating the merit of an entire film on the basis of the credits sequence appears to miss out big time on a more significant message. Using von Trier’s own words: “I think the point to the film is that evil can arise anywhere, as long as the situation is right”. We will explore what that means in a bit.

There is at least one element in the narrative of Dogville that will not go unnoticed: 1) the townspeople’s change from altruistic to vicious and 2) Grace’s change from forgiver to executioner.

Throughout the film we become accustomed to the gracious and kindhearted behaviour Grace displays. We sympathise, if not fall in love, with this mysterious character, despite the fact we know virtually nothing about her past.

Likewise, the residents of Dogville are initially presented to us as modest, honest and lovable people, content with little they can get from the resources provided by the community.

Grace and the Dogville do seem like a perfect match.

However, the relationship between Grace and the townspeople quickly deteriorates, as the townsfolk begin to exploit Grace’s kindness and obligeness, and use the fact that she has been (falsely) accused of robbery, to justify their ever more coercive measures.

It is at this point that we realise that Dogville’s inhabitants harbour malicious intent. We do not view anymore the town as idyllic and altruistic, but rather oppressive, corrupt and sinister.

Grace’s first conversation with one of the town’s residents, Chuck, is particularly revealing.

Chuck asks Grace if Dogville has got her fooled yet – by that he means if she has already realised that the townspeople’s “generosity” is simply an act. Even though Grace thinks the town is charming and people are lovable, this is simply a facade. He thinks the town is actually “rotten, from the inside out”.

According to Chuck, people are greedy like animals, regardless of whether they live in a city or in a small town such as Dogville – the difference is that in a small town they are a little bit less successful. “Feed them enough, they’ll eat until they burst” he said.

I guess this is what von Trier meant by evil arising when the situation is right. Everyone, regardless of who they are or where they live, contain the seed of evil, and will not hesitate to exercise evil if it puts them out of harm’s way.

This pessimistic view of the nature of human beings is particularly interesting when we consider that what we had once believed to be a lovely little town with good people was suddenly transformed into a sinister town with preverse people.

Now, even after the residents of Dogville cruelly subject Grace to sexual abuse and enslavement, she appears to condone the townspeople behaviour.

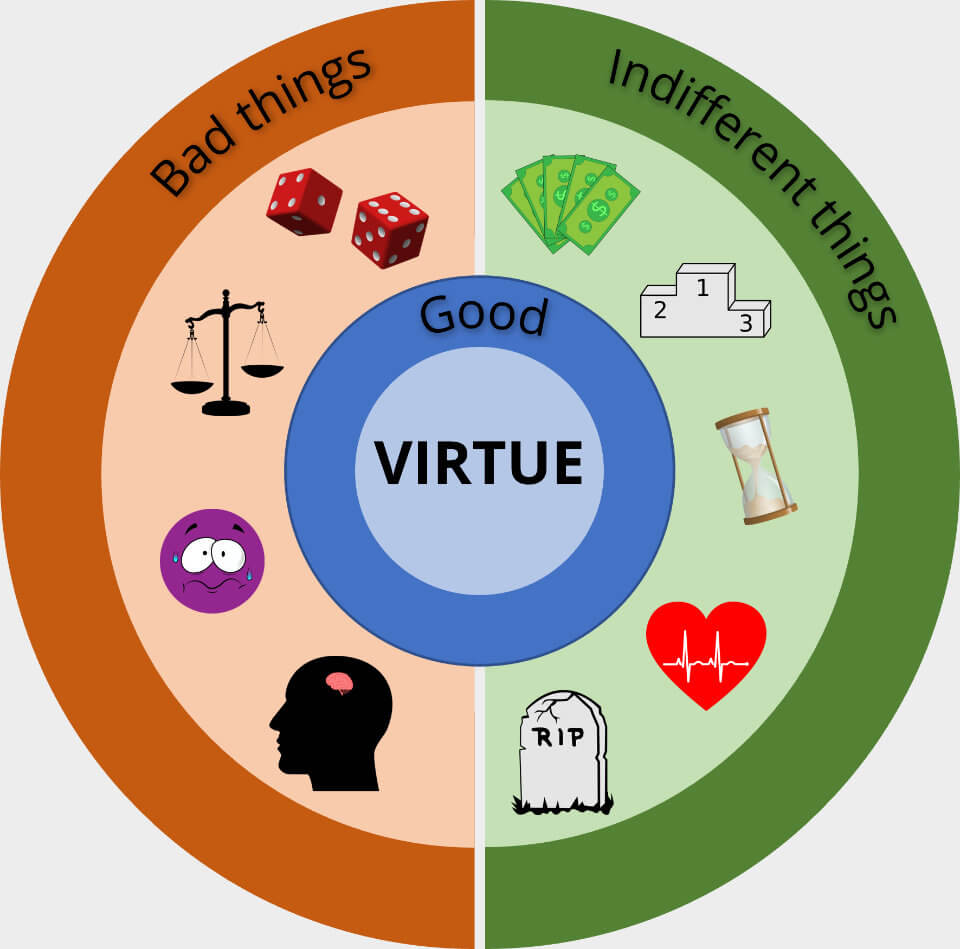

Taking a sneak peak of what will be discussed in this article, Grace’s actions appear to resonate Stoic practices. For example, refusal to dwell in misfortunes, even in the event of enslavement; that reputation, resentment, anger, sadness are all indifferent things that should be handled with emotional detachment; that the only fundamental thing to live for is displaying virtue; that forgiveness of others’ misdeeds is something we should endorse as human beings.

Grace’s mindset, however, undergoes a 180-degree turn after she engages in a discussion about morality with her father. Her change is triggered by the realisation that her moral values are inimical not only to her own well-being but to humanity in general, and, thus, a new morality must be forged – Grace’s own morality.

Grace’s resolution is categorical: Dogville poses a threat to humankind and needs to be purged from the Earth.

As I’ll explain in detail below, Grace’s two antagonistic approaches to matters of morality resemble the opposing philosophical teachings of Stoicism and Friedrich Nietzsche.

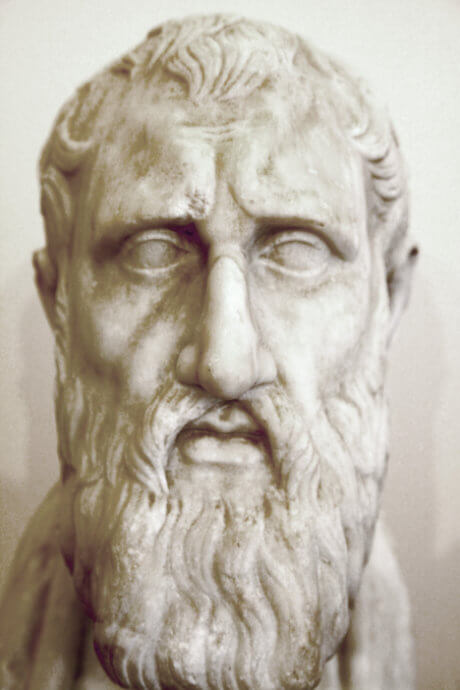

Stoicism is a philosophical tradition that was founded around 301 BC in the city of Athens, Greece by a Cypriot merchant called Zeno of Citium.

The central question in Stoicism can be succintly asked as: How does someone live a good life?

The Stoics used the term eudamonia to describe the fundamental goal in life, which roughly translates to Happiness and Fullfilment.

It might sound like a trivial question. Most of us will probably think that as long as we are healthy, wealthy and have a good reputation within our society, we are essentially living good lives.

As a matter or fact, for the Stoics, none of these things actually contribute to Happiness as I will explain below.

In classical Stoicism, complete Happiness could only be reached if we were living in harmony 1) with our own self, 2) with the universe and 3) with our fellow humans.

We are not born perfect, we have many flaws. Stoics, however, believed we could bring our nature to perfection using the most valuable faculty Nature has provided us with: reason.

They argued that Nature is goal-directed and wants us to perfect ourselves (in this context, Nature doesn’t mean the environment, but rather the whole Universe).

But how can we perfect our character in a way that is according to Nature?

For stoics the answer lays in our capacity for reason: specifically, the only aspect of our lives that really matters is virtue. And all of us contain the seed of virtue.

I find virtue a tough word to explain in the context of Stoicism, but I believe the Stoics meant perfecting human nature by acting with justice, wisdom, courage and self-discipline (the four cardinal virtues).

So, possession of virtue perfects our human nature. And the goal of life handed to us by Nature is to fulfill our potential as human beings (to finish Nature’s work to perfection) – this is what they mean by living in harmony with our own self. Without virtue our lifes will always be void and unfulfilled.

The Stoics were largely influenced by their forerunners, the Cynics, who led very austere lives. For example, Cynics ate simple meals and drank only water; they dressed in cheap and weather-adequate clothing; they had few belongings which they carried in a small knapsack and slept in straw mats in public buildings. Most Stoics did not take such extreme measures, but they considered that Cynics’ arduous lifestyle constituted a short-cut to virtue.

For the Stoics the good in life (i.e., living virtuously and in harmony with ourselves) must be something that 1) is fundamentally praiseworthy and honorable in itself (e.g., self-discipline) and 2) brings about good consequences.

For example, being a professional pianist requires exercising a certain self-discipline – practicing arduously and assiduously and doing your best. Now, let’s say you are a pianist who is often anxious when entering a concert hall. This might happen for a multitude of reasons: maybe you are seeking recognition as a virtuoso, or simply wish people to applaud your performance at the end.

Well, the audience’s reaction is something that is not under your direct control, no matter how well-prepared you are. Perhaps, someone will cough during your performance, distracting you. Maybe there is a fire and everybody has to evacuate. So, desiring external things (like reputation) is likely to make you frustrated, since these desires can be thwarted by unforeseen circumstances.

However, self-discipline is beneficial to the mind and is an honorable quality in itself regardless of what the long-term result will be. So the goal of life should be to improve virtues – in this example self-discipline – since this is directly under your control.

Naturally, not everything that feels good to you is virtuous. For example, we might argue that tranquility of mind is something that we should all aspire to. However, the Stoics would argue that tranquility of mind can still be misused – a psychopath might feel tranquility when murdering someone. So clearly, not everything that feels good brings about good consequences.

So, something is only virtuous if it is considered to be praiseworthy and brings good consequences. So living virtuously (i.e., in harmony with your own self) is all that matters when it comes to complete Happiness and Fullfillment.

Of course, when we act virtuously, feelings of joy might appear. Stoics class these as “healthy passions”. But they stress that these healthy feelings should never be the central goal; they are rather (positive) side-effects of exercising virtue.

At the other end of the spectrum, unhealthy feelings such as worry, envy, sexual lust, malicious joy in the misfortune of others need to be dealt with. If not, they will corrupt the mind and we cannot attain a good life.

These unhealthy passions and desires conflict with the Stoic goal of living in accord to Nature, because they go against our nature as rational human beings.

For stoics, we become slaves to fortune and to our passions, ever attached not only to external objects, but to people as well (e.g., if another person has full control over what we desire, we become enslaved to that person).

For example, let’s say a tyrant is threatening to kill someone or take away a someone’s possessions. An ideal Stoic would view these as indifferent, and the tyrant wouldn’t be able to bring up fear in him, since the tyrant has nothing that the ideal Stoic desires.

Only virtue matters to the ideal Stoic, and possession of virtue offers us freedom from irrational fears and desires.

Stoics believe that the only way to attain Happiness is to look within ourselves rather than external things – if we manage to do so, we will be totally liberated from emotional suffering (free from unhealthy fears or desires).

Note this doesn’t mean we should ignore affection. Quite the contrary! The Stoics highly valued love and natural affection (see below).

The idea was that we should overcome unhealty desires and promote healthier ones. For example, we should naturally love our partner (healthy passion) but not to the point that will make us anxiously worry (unhealthy passion).

Let me put it like this: if you have the feeling that you are not getting what you most desire, or, in contrast, getting what you most fear or avoid, then it means you have become a slave of your passions.

Living in agreement with Nature also means that we need to accept fate as something beyond our control to change it.

If “shit happens”, we should not dwell and complain about it but rather understand that the Universe so wanted it to happen and there is no going back.

Nature or Universe (capitalised) are used interchangebly, and in Stoicism, they refer not only to outer space, but includes literally evertything. If you are religious (and Stoics were indeed very pious) it would be a synonym with God.

For example, if a catastrophe suddenly befalls you, there is no point in ruminating about it, because you can’t really change past events – the past is out of our control, it’s an indifferent thing (see below). Therefore, the wisest behaviour is to willingly accept that it has happened.

Every action we undertake must be done with the knowledge that its outcome is beyond our control and may not turn out as planned – we simply must be detached from these external events (outcomes) and see them as indifferent (we should stop judging them as good or bad).

This is why Stoics’ intentions are never thwarted, because Stoics only desire what are under their control and nothing can take that away from them.

A good analogy is a talented archer shooting an arrow from his bow with the best of his abilities. So the intention is under the archer’s control (he picks the bow, he aims to the target,) but the outcome (the arrow hiting the actual target) is left ultimately up to fate (e.g., a gust of wind may suddenly appear, someone may stumble over the target, etc).

Note that living according to our own human nature and the nature of the Universe are complementary. Acting with virtue allows us to overcome adversities, and in this sense we learn to accept whatever life throws at you instead of complaining.

Now, this does not mean we should have a passive attitude towards life. Definitely not!

For example, if you are in an abusive relationship, the appropriate behaviour would be not to put up with it but actually leave the abusive relationship and participate it to the authorities.

Stoics would do their best to protect themselves from abuse, accidents, etc, but if these things happened, a Stoic would accept the fact that we cannot change the past, and would face the reality of the situation.

In Stoicism, we should exercise good not only for our sake, but also for humanity’s sake in general. This is what Stoics mean by living in harmony with our fellow human beings.

We are social beings, so we should have a philantropic attitude towards others. Thus, natural affection, justice and kindness towards others is part of living virtuosly.

We should love mankind and the only reward we should take from it is virtue By doing good to other people, we help them live without conflict and as a result the society will head towards a Stoic republic – an enlightened communiy of ideal Stoics.

This suggests that the Stoics should love even those who are vicious and our potential enemies. That is, because our enemies have the faculty of reason (the seeds of virtue), they too could turn up to be wise, just and treat us with respect.

There is a good analogy that says that vicious people are like small children – they don’t understand what they are doing so there’s no point in being angry with them.

We do our best (acting with virtue and justice and benevolence) and encourage others towards virtue, whether or not we succeed.

Of course, you might be skeptical and think: “being tolerant with my worst enemies, sure not!”. However the Stoics always avoid responding with anger. For example, they practise putting themselves in other peoples shoes and understand the reason for such and such behaviour (e.g., if people are aggressive towards you, maybe they were brought up in an aggressive family environment).

So, to be a perfect human being, i.e., to live a good and honourable life, you need to act in a way that benefits not only yourself but also others.

A central tenet of Stoicism is that we should direct our behaviour towards good, and avert the bad (folly, injustice, cowardice and vice). As mentioned above, the chief good is virtue (e.g., wisdom, courage, self-discipline, etc), and this is something that is always under our control – in our own feelings, actions and thinking.

Other stuff that most of us might consider good, such as health, wealth and reputation are not relevant to the central task of living a good life. These “external” things are not under our control, and so are classed as “indifferent” when it comes to living a good life.

Indifferent (external) things are neither good nor bad, only our response to them is good or bad. So good and bad only refer to what happens inside our minds.

However, most of us will tend to identify these external things as good, and, in the process, experience feelings of desire for these things. The consequence of this is that they will likely experience frustration at some point in their lives, because indifferent, external things are not directly under their control (think of the pianist example above). In fact, judging external things to be intrinsically good compels us to engage in ever more vice and crave ever more pleasure, wealth and reputation.

Similarly, we might focus too much on irrational judgments about what we believe to be bad or harmful: in this category we find, for example, the fear of pain, poverty and disgrace (which are actually indifferent things, according to Stoics).

So we need to develop wisdom (a virtue), understand what are the most important things in life, learn what is under our control (own actions and judgements) and what is not (indifferent things).

If we manage to perceive external things as just indifferent and accept whatever Nature has provided you with, then we are one step closer to attain eudamonia.

The Stoics believed that even if we managed to prolong one’s life, that would add nothing to virtue – health and wealth, on their own, cannot help a vicious and unfair person attain eudamonia. In fact, wealth tends to corrupt people, in that they engage in more vice.

For Stoics, life, by itself, is neither good nor bad when it comes to living the good life; it is simply the stage on which you can either act virtuously or viciously.

Their point was that even if you suffer from bad health, you can still act virtuosly, and if you do act virtuously, then nothing can affect you, not even bad health.

Put it another way, for the Stoics, it is far more important to have a healthy mind (by that they mean living virtuously) than a healthy body.

I bet most of you are thinking “yeah sure, what a load of mumbo jumbo”.

But, you see, the Stoics did not dismiss having good-health, but they were careful to class these as a “preferred” outcomes, although still irrelevant when it comes to true Happiness and Fullfillment.

In other words, it is far more important to cultivate a healthy character than a healthy body (the idea that the true beauty resides in our character rather than in our looks probably has its roots in Stoicism, as Stoics defined the chief good (virtue) as the beautiful (kalos)).

If you have achieved that level of enlightment, then external things such as bad health and poverty will not affect you. They believed being a good person (living with virtue and free from irrational fears and desires) is completely sufficient to attain Happiness.

However, it’s only natural to seek some external things that have some value in planning the future (they are “preferred”). These naturally include health, wealth, reputation and pleasure as opposed to illness, poverty, disgrace and pain. However, these preferred indifferents should not be the basis on which Happiness is assessed, and should be experienced with emotional detachment.

At the end of the day, the key is to use preferred things wisely (with wisdom and virtue), and this includes, for example, philantropy towards others (i.e., helping and wishing others well).

Discussing Nietzsche now may look like a bit of a curious leap to say the least. However, bear with me for a minute as both Stoicism and Nietzsche’s philosophies will be important for our discussion of Dogville.

The way we use to make sense of the world is through morality – principles regarding to what we believe is right/wrong or good/bad. Whenever we act, we base our actions according to these principles we have internalised (e.g., I should not steal, I should be a good husband, I should be compassionate).

Up until about the end of the 18th century, Christianity was still in full swing across Europe. Christians acted according to God’s values and were taught that obedience to those values bought them a place in heaven.

And so, they were encouraged to think of this world as only a preparation for a better world, the afterlife; that they would be rewarded for good deeds and punished for bad ones; and that piety, forgiveness and compassion should be the order of the day.

They lived their lives according to God’s moral principles. But what if people began to call these principles into question?

At the end of the 19th century, with advances of technology and a shift towards scientific thinking, religious faith showed a drastic decline in nearly every society.

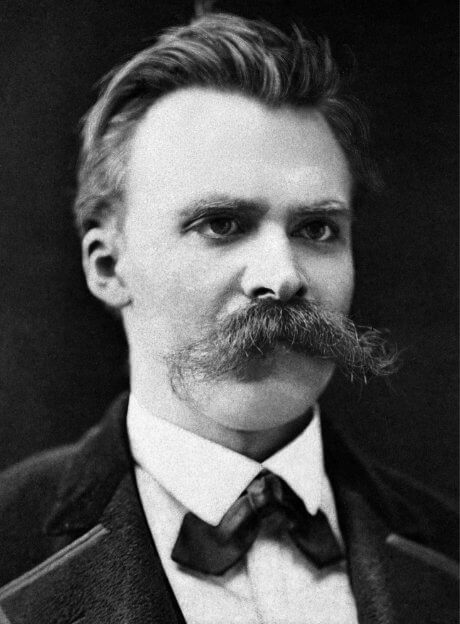

Friedrich Nietzsche, a German philosopher well-known for his attacks on Christianity, famously declared that “God is dead”, in the sense that people stopped believing in God.

Even though most of Nietzsche’s philosophical ideas reflect a deeply anti-christian sentiment, when Nietzsche declared that “God is Dead”, he didn’t only specifically mean the christian God. He actually meant any doctrine set at denying this life on Earth in favour of a metaphysical world (a world beyond this one, such as the celestial world of Christianity).

Because people’s beliefs were often based on metaphysics (e.g., that this world is somewhat imperfect and only a preparation for the afterlife), Christians are taught that they should deny the material world, and hope for a celestial, purer and better world. However, if God is dead, we are now faced with a reality in which none of our previous values hold, including the prospect of a better world beyond this one.

Nietzsche believed that when the meaning and values we believe in are shattered, we enter a depression, in which we feel that nothing else makes sense, that our life is essentially meaningless devoid of purpose (consider a devout Christian who suddenly has lost her faith). Nietsche called this condition nihilism, and he believed humanity were gradually entering this state of confusion and absurdity.

To Nietzsche, however, this was not a reason to despair. In fact, he believed that we should take the opportunity to embrace this emptiness, because now we are really free from the reigns of divinity and delusional idealism.

Nietzsche proposed a complete “revaluation of all values”, that is, to question our ideas about ethics and the meaning of life and start forming our own values based on what we desire.

We might have always believed a certain attitude towards life is good, when in fact it is life-denying.

For example, a homossexual individual might hide his true sexual orientation for fear that either his family or society might not accept his sexual preferences.

Nietzsche would argue, however, that we should simply follow our instincts, have the pride and strength to follow them through. This is, for Nietzsche, life-affirming – we are not bound to external rules imposed on us, we become truly free.

He actually goes further and suggests that we transform ourselves into gods. This involves the destruction of the old world in order to create a new order that does humanity justice.

Enter the Übermensch.

Übermensch is a term that is often translated to Superman, which, personally, I think is an unfortunate translation nowadays, as it evokes images of the famous DC comics hero. Beyond-man or Over-man have been proposed as better translations, but I’ll stick to the German word.

In many texts, we see this term being associated with a single individual, but, in fact, it is more of a superior stage of humankind. For example, Homo Sapiens is not a single individual, but it represents a certain stage of human evolution. The Übermensch would be an even superior stage. In fact, the distance between Übermensch and Homo Sapiens, would be equivalent to the distance between the Homo Sapiens and non-human apes!

Now, Nietzsche wasn’t referring to the Übermensch as the result of a purely evolutionary process. Rather, he believed the Übermesnsch to be superior in the intellect, best characterised by it’s ability to leave behind Christian, ascetic and pessimistic beliefs that undervalue our life in this world. The Übermensch thrives in personal autonomy (assert that we are different from everyone else), and staves off assimilation by any community whatsoever.

But what are the steps to become a Übermensch?

Nietzsche viewed every living being as a manifestation of disparate (unconscious) forces, an idea that would soon shape Freud’s conception of the Unconscious mind (although Freud never actually acknowledged it). It is these forces that determine our behaviour, for example, whether we show altruism or egoism.

A complete revaluation of values consists in accepting these forces (both good and bad) that reside deep within our bodies. Nietzsche calls this “will to power”. This means making our own decisions, not obediently follow some “herd” mentality. We should create a kind of life that we are proud of and adhere to our own values, the values we want to live for, without caring what other people think or do. What matters is our own sense of good.

In other words, the Übermensch isn’t afraid to assimilate and work with these unconscious forces that reside in him- or herself, and doesn’t feel guilty about it. They have the courage to overcome their flaws and fears and have the ability to redifine their moral values.

Note that “will to power” is not a will to dominate others as the name might imply, but rather a drive to assert oneself, make ourselves unique and different. Perhaps replacing the word “power” with “potential” would be a better approximation of Nietzsche’s intentions.

A good example is how Nietzsche views Christianity’s stance on sex. Christianity advocates chastity and sees sex as something sinful and preverse. However, to Nietzsche, this goes against our very natural instinct to procreate – the most fundamental affirmation of life.

Of course, Nietzsche isn’t suggesting you should act amoral – I believe Nietzsche’s idea was to use instinctive forces in creative and useful ways that benefit society and humanity in general (such as in art).

On the other hand, Nietzsche proposed, somewhat controversially, that society shouldn’t care about providing the greatest well-being for the sake of the majority of people. Rather, he believed that any human culture is perfectly justified by forming a few great individuals (in fact, Nietzsche had such aversion to “herd mentality”, that he went as far as suggesting to “sacrifice” them if that sped the arrival of the Übermensch).

He went further saying we should only love man insofar as it leads us to the Übermensch.

To Nietzsche, if people embraced their “will to power” (i.e., your commitment to make your own moral values, rather than follow “herd mentality”), they would think of good and bad as anything that ultimately benefited or hindered them, respectively, when working towards their goals.

This means that if lying brought about fullfillment, people following master morality would have no compunction in doing so. Nietzsche believed, again controversially, that even oppression would be justified if it meant the greater good.

So, for master morality the good qualities are strength, power, glory, greed and courage, as these are often needed when we wish to impose our views on the world.

The majority of people, however, would not be in the position to fulfill their goals. So they see masters’ traits with envy and jealousy.

Because they cannot attain the same attributes as masters have, they turn those master-morality attributes, such as strength, power, glory, greed and courage into evil “things”. For the slave-morality cohort, “good” becomes humility, forgiveness, compassion and altruism.

To exemplify the difference between master and slave morality in a context we are all familiar with, let’s imagine a couple having dinner at a restaurant. The man follows slave-morality so let’s call him Slavie; the woman follows master-morality so let’s call her Mastie.

Now, when the waiter comes with their orders he accidentally trips and spills all the food and drinks onto Slavie’s and Mastie’s clothes.

Mastie gets up, and ignoring inquisitive looks, she speaks with firmness and determination that the restaurant must pay for a new dress.

Slavie tries to calm Mastie down. Although his suit is also ruined beyond repair, he says that the waitress cannot be blamed, that this was simply an unfortunate accident, and that she is embarassing herself.

Nietzsche would see Slavie’s behaviour as turning the master-morality of Mastie (i.e., her strength in taking what she wants) into a vice (i.e., violent behaviour and irrational thinking). In fact, since slaves are unable to act their strength, they consider its opposite a virtue. For example, incapable of taking revenge on the restaurant, Slavie adopts a stance of forgiving.

Now, there are many texts revealing why Nietzsche wasn’t fond of Stoicism, but I would go as far as saying that I believe there are many more similarities than dissimarities (but I’ll leave that for the comment/forum sections).

What Nietzsche disliked about Stoicism was not really Stoicism as a philosophical doctrine, but rather the idea of a rules-based system that should be applied to each and everyone of us.

Stoicism, in one way or another, promotes eudamonia as an ideal way of living, that every single one of us should aim for. If we all follow Stoicism’s notion of virtue, then we will all lead the same good life Nature had planned for us.

Nietzsche abhorred this kind of egalitarianism, as he believed it crushed individuality and hampered the expression of talent in truly great individuals. Humans should create their own set of values, find their own way, instead of following philosophies that emphasize the pursue of some ostensibly objective truth, like Stoicism’s virtue.

A second point of Nietzsche’s critique was that Stoicism teaches us to treat all external things as indifferent, and to detach our feelings from them. Nietzsche, in contrast, believed we should not ignore these energies. We should embrace our instincts, both good and bad, and channel them into creative activites, to assert ourselves and to become different from everyone else.

A third point of criticism, Nietzsche argued that morality is nothing more than self-interest in disguise. Whereas Stoics have an established idea of what it means to be virtuous, Nietzsche tells us that behind most human actions (some of which we might believe are purely virtuous) hide unconscious forces that might not be at all that noble.

For example, let’s say you are waiting in a long line at the supermarket, and suddenly another cashier opens next to you. People behind you are quick to realise this and rush to be the first ones to get there. You don’t find this fair. After all, you have been waiting longer and deserve to be the first one to get attended. You think how uncivilized that behaviour is and that people should be more respectful.

Rather than agreeing with you, Nietzsche would probably argue that the reason you are upset is not that you find respect and civility noble. Maybe you wish (unconsciously or not) that you were more like the people that arrived first at the cashier. However, you dare not, for fear of being told off.

So, behind your seemingly moral attitude hides a very non-virtuous sentiment: envy.

So you learnt about two distinct schools of philosophy: Stoicism and Nietzsche’s so-called “philosophy of the future”. Let’s go ahead and see how we can apply them to the film Dogville.

If you have read the Stoicism section above, you will immediately appreciate how Stoics would find Grace’s character appealing.

She appears to love unconditionally, while accepting her fate when things turn for the worse. For example, when the residents of Dogville express their reluctance into allowing Grace to hide in their town, she does not question them and does not attempt to convince the townspeople otherwise. In fact, she accepts it may be dangerous for the citizens and states the facts with fortitude.

During this first meeting, one of the townsfolk, Chuck, asks why they should trust Grace. Instead of trying to appeal to their good nature, Grace simply agrees and says “He’s right, why should you trust me?”. In a subsequent meeting, she even suggests another voting when the police hangs a “Wanted” poster.

A crucial point in the film is when a light is shone over the village. This happens shortly after Grace becomes enamoured with the town and every little thing it has offers. She calls Dogville beautiful, a place where people, despite living under harsh conditions, have hopes and dreams. She even seems enchanted with the hideous figurines at the shopping window.

When Grace prepares to leave Dogville, as she believes the townspeople voted her out, she isn’t resentful. The narrator mentions that she has shown her true face to Dogville, that she genuinely cared for the town and left a trace there that she took pride for.

In other words, Grace acted with virtue – she helped the townspeople not because she was expecting something in return but for the sake of helping out. As I explained in the section on Stoicism, only virtue is important for attaining complete Happiness – nothing else matters.

Of course, Grace felt that she would rather stay in Dogville (what Stoics would call a preferred indifferent), but the most important outcome of her stay was that she acted virtuously.

Another indication that Grace is following Stoicism logic is when she notices that Tom’s father doesn’t want any help from Grace. She says he doesn’t like her, and that he has all the right to feel that way.

Still, she does not go to extreme lenghts to ingratiate herself with him – in fact, she is quite conformed with the fact Tom’s father might not like her (she says: “if he doesn’t like me, then he doesn’t like me”). That could again be construed as a Stoic attitude – we cannot control other people’s actions, judgments or feelings, they are out of our control, so there is no point in ruminating over this. Grace, as a good Stoic she appears to be, does not let that affect her life in the town, and she does not change her behaviour towards Tom’s father.

All of the points I described above all seem to imply that Grace is willing to accept her fate, whatever that may be. Remember, for Stoics, both past and future are indifferent, as we cannot control them.

Third, Grace displays unusual empathy for other people. Despite the townspeople being blatantly mean to her as her stay is prolonged, she still behaves calmly and almost indifferent to their criticism – another Stoic characteristic.

For example, after the two-week probation period has passed, the narrator says that Grace was fond of all the townspeople, including those who had been reluctant and showed a certain hostility towards her.

When they ask her to work longer hours for less pay, she says she will certainly do it, but she is concerned about the well-being of the townspeople; that they perhaps prefer that she left the town, because her staying might be too dangerous for them.

It brings to mind the Stoicism view that we should live harmoniously even with our enemies.

More evidence of Grace’s ostensible Stoic practices is how she endures complete humilliation.

She allows Dogville’s residents all kinds of abuse, and still she does not condone any of them. In fact, she appears to defend their actions by saying that they must have their reasons for behaving in this vicious manner – this is taking Stoicism to the extreme, as Stoics advise us to put ourselves in our enemies’ shoes, and understand the reasons behind their vicious behaviour.

Even in the face of such adversity, Grace still claims she does not hate the townspeople because she knows that they are simply weak. After Chuck rapes Grace, she tells Tom that Chuck is just not mentally strong, that he looks strong but he isn’t.

In relation to this, Tom suggests that Grace gives a speech so that she tells all the wrongdoings the people of Dogville have done. Grace dismisses this suggestion because she thinks that will provoke them, as they will probably not want to hear what Grace has to say. Tom then compares them to children who refuse to take their medicine; that they will be furious at first but in the end they will understand it was for their own good.

Tom continues saying she shouldn’t be hateful or reproving; that the townsfolk will realise that they have been acting unjustly and that she is the victim. Once this comes to fruition, she will then be able to show forgiveness.

Although Tom’s intentions are clearly nefarious, Grace appears to share his view as the conversation with her father later in the film reveals. Grace asks her father why should she not forgive, why should she not show mercy. She argues that the townspeople vicious behaviour is the result of the very harsh circumstances they face, and, therefore, should be forgiven.

Clearly, this echoes Stoic philosophy that vicious and foolish people are like small children throwing a tantrum. They act foolishly because they don’t yet understand what they’re are doing, so it makes little sense to resent them or to be angry with them.

If Dogville’s inhabitants act immorally, according to Grace, it’s because they don’t know any better. As her father, later on, will dismissively respond: “The only thing you [Grace] can blame is circumstances. Rapists and murderers may be the victims, according to you.”.

A direct reference to Stoicism occurs in the film when Grace is confronted by Vera (Chuck’s wife) and two other women.

Grace tries, in vain, to appease a very distraught Vera and reminds her that she has been teaching the doctrine of Stoicism to Vera’s children. Vera, however, forces Grace to watch her break her beloved figurines, and challenges her not to cry as that would show she is a real Stoic. This scene is suggestive that Grace is, indeed, a practicing Stoic.

Still in this scene, the narrator adds that Grace had considerable practice at holding back her emotions. For the Stoics, external things are indifferent to Happiness, so they practice being emotionally detached from them.

One could argue that Grace is not showing Stoic values, but rather displaying Christian values. Indeed, there are similarities between Stoicism and Christianity that would make this interpretation equally valid (e.g., the teaching that we should love even our enemies; that we should weed out unhealthy passions, such as greed and envy; that we should accept our fate, etc.).

However, it seems that von Trier was careful not to incorporate Christian ideology into the film. As far as I’m aware, there is only a single mention of God (and not necessarily a Christian one) in the car scene when Grace says to her father “To plunder, as it were a God-given right – I’d call that arrogant”.

The absence of references to “God” in Grace’s dialogues is a strong indication that Grace is not adhering to any particular religious belief, but rather Stoic ideology, given the evidence outlined above.

As we begin to approach the end of the film, Grace’s thinking is at times overcome by what Stoics would consider flawed thinking.

For example, when the disabled girl in the wheelchair wets the bed, Grace notices an irritating feeling taking over her. Annoyed at the idea that she is just wasting her time she says “Nobody gonna sleep here”. Grace appears taken aback by the words she had muttered, whilst the narrator comments “where had these ominous words come from?”.

Shortly after she meets Tom and asks him if he actually threw away the card the gangster gave him. Upon realising he didn’t, she says that was stupid. Her comment strikes us as unusual now, because from the beginning of the film Grace has always displayed an utterly non-judgmental attitude towards eveyone.

Thus, I believe these two scenes represent a pivotal moment in the film, as it heralds Grace’s change from forgiver to executioner. As we will see, this change reflects the move from slave- to master-morality.

Even though Grace is cognizant of the townsfolk immoral behaviour, she doesn’t condemn them but rather believes they are victims of circumstances. As I mentioned earlier, this attitude of putting onself in other people’s shoes as a means to understand their perspective, regardless of how wicked it appears, seems to resonate Stoic practices.

During the conversation with Grace’s father, he calls her arrogant as he is convinced that she is exonerating the townspeople simply on the basis of their ignorance – they are unable to see the moral implications of their actions, and so she pities and forgives them.

This is a very Nietzschean interpretation in my view.

Putting it loosely, Nietzsche believed that pity is a scourge of the mind and there is nothing better to demonstrate that than using Nietzsche’s own words:

“Pity is a waste of feeling, a moral parasite which is injurious to the health, “it cannot possibly be our duty to increase the evil in the world.” If one does good merely out of pity, it is one s self and not one s neighbour that one is succouring. Pity does not depend upon maxims, but upon emotions. The suffering we see infects us; pity is an infection.”

So, to Nietzsche, pity is nothing more than an unconscious way to justify our self-interest. Whenever someone feels pity, Nietzsche would argue that this seemingly moral attitude hides very non-virtuous sentiments, such as arrogance.

According to her father then, Grace isn’t showing pity and forgiveness because she really cares about the townspeople. She is simply attempting to vindicate her inaction by believing that others are below her regarding ethical standards. In other words, her ineptitude to take action and put a stop to the townspeople malevolence is turned into pity for her abusers (an attitude not too dissimilar of slave-morality, more on that below).

At first, Grace dismisses her father’s points, and upholds her belief that we should feel pity and grant forgiveness to the townspeople, despite their corrupted conduct.

However, as she walks around the town once more, she gradually begins to accept that her attitude of self-sacrifice and pity is tantamount to denying the value of her own life. In attempting to live a life in Dogville on the sole basis of virtue, self-sacrifice and forgiveness, Grace realises that she has denied life.

She realises that her passive attitude, her pity and her compassion towards her abusers go to such extremes that it borders complacency in the face of injustice.

As the narrator describes: if Grace had done to others what the townspeople had done to her, she couldn’t possibly justify any of her actions.

This epiphany completely overturns Grace’s values, in what Nietzsche would call “a revaluation of all values”.

Interestingly, at that exact moment, a new light is shone over the town. Remember the first light that welcomed the arrival of Grace the Stoic, full of love, mercy, justice and compassion for the town and its residents?

Well, this is a different light.

As the narrator points out, the light that had once shined so merciful over the town, is now penetrating every flaw in the people. The light metaphorically represents Grace’s change from forgiver to executioner.

As I will describe below, this new light could be construed as the the light of master-morality, the light announcing the arrival of the Übermensch.

In other words, this new light represents her realisation of the futility of her old values and mental structures; the moment when she begins to see beyond false illusions of mercy, pity and forgiveness; the moment when the old Grace can finally be surpassed.

Grace’s methamorphosis comes with the realisation that this town represents an obstacle that must be eradicated, in order to not cause harm to anyone else. Grace thinks that wiping out the town is doing humanity a favour, a chance for the emergence of the Übermensch.

With this new Grace, we see Nietzsche’s “will to power” idea materialising. Remember, “will to power” is not necessarily a will to dominate others (although oftentimes it can be), but rather to assert oneself, make ourselves unique and different.

There is an interesting play with the word “power” in the film. Grace asks her father when would she be given power, at which her father replies, right away. I believe power here refers to something more transcendental: power in the sense of dominion over your own ideals, the way Nietzsche encouraged us to think.

Graces drastic change in her moral views also reminds me of the duality of slave/master morality that Nietzsche proposed.

Prior to the arrival of her father, Grace is evincing a prototypical “slave-morality”, in the sense that given her impotence in acting with strength to fight off abuse, she recoils into a position of submission, and justifies this position by calling the others weak of mind.

Nietzsche insisted that followers of slave-morality will turn a situation of not being able to take revenge into forgiveness – exactly the kind of mindset Grace appears to be demonstrating.

After the conversation with her father, Grace seems to adopt a master-morality. She decides to take an active stance by ordering the killings and burning down the entire town. She is guided by her instincts, by her desires, by her ideals of what is good, what benefits humanity – what Nietzsche would call a true master.

To her mind, Dogville is pernicious and must be sacrificed for the greater good. Out of all residents, only Moses, the dog, is left unscathed from Grace’s application of her renewed morality.

What would Nietzsche say about that?

If you haven’t noticed already, I really revel in good philosophical discussions. Dogville has certainly made an indelible impression on me with that fateful exchange of moral views between Grace and her father.

In fact, I’d go as far as saying that all the clues you need for grasping the meaning of the film are contained within the last 20 minutes or so, during the time that conversation takes place.

As I discussed at great length above, Grace’s radical transformation from forgiver to executioner can be explained by the antagonistic philosophies of Stoicism and Nietzsche, respectively. In short, Grace’s Stoic moral and ethical values of forgiveness, compassion, justice and virtue, were simply ill-suited in a town such as Dogville, whose devious residents were quick to exploit Grace’s kindness. As Grace herself realised, their vicious behaviour couldn’t possibly be vindicated, and for humanity to evolve, a newly forged morality had to be born: a master-morality.

While the new Grace shows no mercy whatsoever (she orders the killing of every single resident, including the children), we cannot but feel that she does not enjoy this “power”. Her demeanor during the destruction of the town is suggestive that she only did what she did because she believed it to be what was most beneficial to humanity, not because she enjoyed it. As Nietzsche would have argued, oppression and sacrifice are sometimes required in order to bring humanity forward.

Grace followed Nietzsche’s thought to the letter.

Both classical Stoicism and Nietzsche’s original philosophical ideas were formulated at a time when religion had a much firmer position in the society.

With most governments now turning to science when passing new legislation (the current pandemic being a perfect example of that), Nietzsche’s idea of the “Death of God” is considered by most scholars outdated, as it pretty much already occurred (at least in the Western world).

Likewise, it is difficult to imagine how anyone would fit in in our 21st century society, following a lifestyle that is purely based on classical Stoic values.

Having said that, both currents of philosophy have certainly evolved to meet modern demands.

Current practitioners of Stoicism, for example, are adapting their ideas to several branches of Psychology; for example, some of their teachings have now been incorporated in many cognitive behavioural therapies.

For my analysis of Dogville, I remained mostly faithful to the original teachings – call me old-fashion :)!

See you in the next article!

Books

Robertson, Donald. Stoicism and the Art of Happiness. Teach Yourself.

Llácer, Toni. Nietzsche – El superhombre y la voluntad de poder.

Youtube

This was a magnificent review of a great movie. I enjoyed your review as much as I enjoyed the movie itself. However, I, with a background in philosophy and German, read a lot of Nietzache in both German and English. I also know how Nietzsche was MISUSED to back up NAZI propoganda. I am not trying to say that you were inaccurate in what you said about Nietsche’s writing. but your metaphors and examples completely missed the target, in my opinion. You described a Nietsche who would resemble Charles Atlas, and who, if he was coming towards you on the street would look like a bruiser.

In reality, Nietsche was a smallish weakling with a huge brain. Nietsche was all about the brain. Nietsche would never try to be first in line in a crowded store. Probably the only time in his life that he got into a fight, was when he tried to stop a man on the street from beating his horse. and by doing that, he had a complete mental and physical breakdown, and never recovered,

Nietsche was not a boxing champion, he was a thinking champion.He was the son of a Lutheran minister. He was not religious, but he was a genius.

Philosophy-wise, Nietsche was one of the first Existentialists. He didn’t believe in trying to figure out what reality was, he believed in using your brain to mold reality. Your brain, not your bicepts.And I think my version of Nietsche also works extremely well in analyzing this movie. Grace was ten times the IQ of anyone in Dogville. She was teaching kids stoicism. She could understand what was going on around her. Physically, she was more like Nietsche than Marcus Aurelius. She was raped and abused daily until she decided that changing reality was much more effective than trying to cope with it. So, she used her mind to mold reality by having daddy put the wiseguys to work and “fix” the town. You go, girl!

Great movie, Great philiscophical review above.

Hi David,

Many thanks for your insightful comment, and I’m happy you enjoyed the article!

I completely agree with what you say above. The examples described in the article were just my attempt at linking Nietzsche’s teachings with more mundane, daily-life experiences that readers could relate to.

In particular, people getting angry at others skipping the line probably aligns with Nietzsche’s proposition that seemingly honourable attitudes can be often expressions of self-interest or envy in disguise. I admit though that there’re likely better analogies.

But, yes, Nietzsche would have (almost surely) sucked it up and stayed in line 😀

I was looking for a satisfying analysis after watching the film with my wife. It was my 3rd or 4th time seeing the film, and it’s one of my all time favorites. Now, in my 40’s, I think I fully appreciate the philosophical implications. Your essay really hit the nail on the head for me. Thank you.

Hi Familydude,

You’re very welcome, and thank you for your comment!

I watched Dogville for the first time when it came out in the cinema back in 2003 and I loved it. Rewatched it after 20 years with renewed eyes and a tad more philosophical, and it was a whole different experience.

Only great films have this capacity to make us feel differently as we mature – Dogville is certainly one of them!

I wholeheartedly agree. I’m now interested in learning more about Nietzsche. Do you have a recommendation on where to go, or what book to begin with? Thanks

I read two or three books on Nietzsche for a general overview of his work, as well as translations of some of original texts such as The Antichrist (which were surprisingly not extremely difficult to follow).

However, there are plenty of youtubers out there with a Philosophy background who do a very good job at explaining philosophical ideas with plenty of quotidian examples, and this is what I recommend as a first dive into Nietzsche. Two of my favourite channels while writing up the article were: Personal Power and Philosophy Vibe.

Good luck! I had a lot of fun learning Nietzsche’s philosophy, and I’m sure you’ll do too 😉

Incredible article! This movie put me in quite a depressive episode but your analysis really helped me understand why it made me feel so powerless. I also found Grace’s change to be reminiscent of Camus’ philosophies on absurdity and sincerity.

Hi Mike,

Thank you very much for your comment!

I have to admit that I know very little about Albert Camus’ philosophies, but you’ve certainly piqued my interest. So thanks for the suggestion, I’ll check it out!

Outstanding

Great article! Dogville is one of my favorite movies and to be honest I identify with Grace regarding her stoic values. Now I am struggling a little with the consequences of my virtue approach towards people. At some point earlier I decided to reject the master attitude since it wasn’t always understood (i.e. at work), I fell into the herd mentality trap. It is not easy, you try to be good and go beyond for others – they kick you in the butt, you control the situation – they are scared of you.

After this read I am at least a little bit more aware and eager to get a better understanding of Nietzsche’s position.

So in some way, you changed my life 😀 thanks!

Hi harofld. Thank you for your comment, and I’m very happy to know that you found the article helpful.

Indeed, I identify strongly with what you said about the difficulty in displaying a type of master morality in places where it is often misunderstood. I have to confess I also tend to follow a herd mentality: trying to appease others, being diplomatic and uncontroversial and exercise good judgement, even if that puts me at a disavantage sometimes.

Nevertheless, the research I did for Dogville, placing Stoicism and Nietzsche’s philosophy in a sort of opposition, was at least helpful in making me aware of some of my own limitations.

I don’t think I’ve ever read an article or a review this good. It captures everything that it needs to capture, in terms of dissecting the essense of the movie AND in terms of debating through different philosophies. 100/100. Thank you so much for putting in the effort and time. Remarkable.

Hi Kate. Thank you very much for your very kind words and I’m really glad you enjoyed the article. I’ll definitely do my best to keep publishing these articles as often as I can 😉 Hope to hear from you again soon!

This article was as good as the movie, I really appreciate the time the autor took to write it, as a practitioner Stoic I loved to read a film review that was very well informed. And beyond that it was just so complete and satisfying to read. Thank you, looking forward to read the other articles.

Hi Ztoicfox. Many thanks for the kind words, I’m really happy that you enjoyed the article. It’s comments like yours that really make my day :). Cheers!

Great

Loved the movie but…

I loved the movie, the concept, the aesthetic, the philosophy behind and the acting! All great, my only but, was the camera work, I understand handheld makes total sense with the whole line of the movie but personally it was to pronounce. If it was made more subtle I would have given 5 stars.