This post is part of a larger deep dive

Curious about the role of Stoicism and Nietzsche's philosophy of the future in Dogville? Check out Dogville Explained!

Or read the full Dogville article!

This post is part of a larger deep dive

Curious about the role of Stoicism and Nietzsche's philosophy of the future in Dogville? Check out Dogville Explained!

Or read the full Dogville article!

So you learnt about two distinct schools of philosophy: Stoicism and Nietzsche’s so-called “philosophy of the future”. Let’s go ahead and see how we can apply them to the film Dogville.

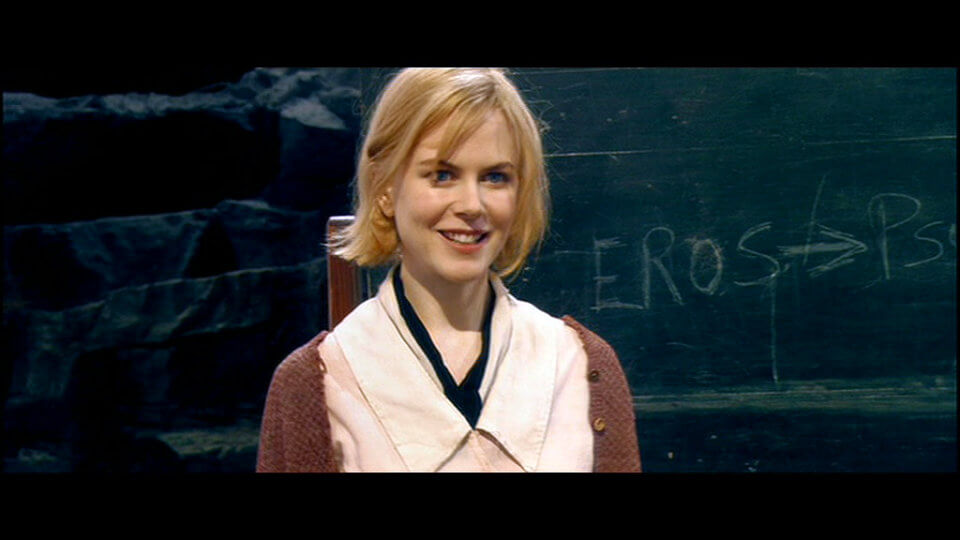

If you have read the Stoicism section above, you will immediately appreciate how Stoics would find Grace’s character appealing.

She appears to love unconditionally, while accepting her fate when things turn for the worse. For example, when the residents of Dogville express their reluctance into allowing Grace to hide in their town, she does not question them and does not attempt to convince the townspeople otherwise. In fact, she accepts it may be dangerous for the citizens and states the facts with fortitude.

During this first meeting, one of the townsfolk, Chuck, asks why they should trust Grace. Instead of trying to appeal to their good nature, Grace simply agrees and says “He’s right, why should you trust me?”. In a subsequent meeting, she even suggests another voting when the police hangs a “Wanted” poster.

A crucial point in the film is when a light is shone over the village. This happens shortly after Grace becomes enamoured with the town and every little thing it has offers. She calls Dogville beautiful, a place where people, despite living under harsh conditions, have hopes and dreams. She even seems enchanted with the hideous figurines at the shopping window.

When Grace prepares to leave Dogville, as she believes the townspeople voted her out, she isn’t resentful. The narrator mentions that she has shown her true face to Dogville, that she genuinely cared for the town and left a trace there that she took pride for.

In other words, Grace acted with virtue – she helped the townspeople not because she was expecting something in return but for the sake of helping out. As I explained in the section on Stoicism, only virtue is important for attaining complete Happiness – nothing else matters.

Of course, Grace felt that she would rather stay in Dogville (what Stoics would call a preferred indifferent), but the most important outcome of her stay was that she acted virtuously.

Another indication that Grace is following Stoicism logic is when she notices that Tom’s father doesn’t want any help from Grace. She says he doesn’t like her, and that he has all the right to feel that way.

Still, she does not go to extreme lenghts to ingratiate herself with him – in fact, she is quite conformed with the fact Tom’s father might not like her (she says: “if he doesn’t like me, then he doesn’t like me”). That could again be construed as a Stoic attitude – we cannot control other people’s actions, judgments or feelings, they are out of our control, so there is no point in ruminating over this. Grace, as a good Stoic she appears to be, does not let that affect her life in the town, and she does not change her behaviour towards Tom’s father.

All of the points I described above all seem to imply that Grace is willing to accept her fate, whatever that may be. Remember, for Stoics, both past and future are indifferent, as we cannot control them.

Third, Grace displays unusual empathy for other people. Despite the townspeople being blatantly mean to her as her stay is prolonged, she still behaves calmly and almost indifferent to their criticism – another Stoic characteristic.

For example, after the two-week probation period has passed, the narrator says that Grace was fond of all the townspeople, including those who had been reluctant and showed a certain hostility towards her.

When they ask her to work longer hours for less pay, she says she will certainly do it, but she is concerned about the well-being of the townspeople; that they perhaps prefer that she left the town, because her staying might be too dangerous for them.

It brings to mind the Stoicism view that we should live harmoniously even with our enemies.

More evidence of Grace’s ostensible Stoic practices is how she endures complete humilliation.

She allows Dogville’s residents all kinds of abuse, and still she does not condone any of them. In fact, she appears to defend their actions by saying that they must have their reasons for behaving in this vicious manner – this is taking Stoicism to the extreme, as Stoics advise us to put ourselves in our enemies’ shoes, and understand the reasons behind their vicious behaviour.

Even in the face of such adversity, Grace still claims she does not hate the townspeople because she knows that they are simply weak. After Chuck rapes Grace, she tells Tom that Chuck is just not mentally strong, that he looks strong but he isn’t.

In relation to this, Tom suggests that Grace gives a speech so that she tells all the wrongdoings the people of Dogville have done. Grace dismisses this suggestion because she thinks that will provoke them, as they will probably not want to hear what Grace has to say. Tom then compares them to children who refuse to take their medicine; that they will be furious at first but in the end they will understand it was for their own good.

Tom continues saying she shouldn’t be hateful or reproving; that the townsfolk will realise that they have been acting unjustly and that she is the victim. Once this comes to fruition, she will then be able to show forgiveness.

Although Tom’s intentions are clearly nefarious, Grace appears to share his view as the conversation with her father later in the film reveals. Grace asks her father why should she not forgive, why should she not show mercy. She argues that the townspeople vicious behaviour is the result of the very harsh circumstances they face, and, therefore, should be forgiven.

Clearly, this echoes Stoic philosophy that vicious and foolish people are like small children throwing a tantrum. They act foolishly because they don’t yet understand what they’re are doing, so it makes little sense to resent them or to be angry with them.

If Dogville’s inhabitants act immorally, according to Grace, it’s because they don’t know any better. As her father, later on, will dismissively respond: “The only thing you [Grace] can blame is circumstances. Rapists and murderers may be the victims, according to you.”.

A direct reference to Stoicism occurs in the film when Grace is confronted by Vera (Chuck’s wife) and two other women.

Grace tries, in vain, to appease a very distraught Vera and reminds her that she has been teaching the doctrine of Stoicism to Vera’s children. Vera, however, forces Grace to watch her break her beloved figurines, and challenges her not to cry as that would show she is a real Stoic. This scene is suggestive that Grace is, indeed, a practicing Stoic.

Still in this scene, the narrator adds that Grace had considerable practice at holding back her emotions. For the Stoics, external things are indifferent to Happiness, so they practice being emotionally detached from them.

One could argue that Grace is not showing Stoic values, but rather displaying Christian values. Indeed, there are similarities between Stoicism and Christianity that would make this interpretation equally valid (e.g., the teaching that we should love even our enemies; that we should weed out unhealthy passions, such as greed and envy; that we should accept our fate, etc.).

However, it seems that von Trier was careful not to incorporate Christian ideology into the film. As far as I’m aware, there is only a single mention of God (and not necessarily a Christian one) in the car scene when Grace says to her father “To plunder, as it were a God-given right – I’d call that arrogant”.

The absence of references to “God” in Grace’s dialogues is a strong indication that Grace is not adhering to any particular religious belief, but rather Stoic ideology, given the evidence outlined above.

As we begin to approach the end of the film, Grace’s thinking is at times overcome by what Stoics would consider flawed thinking.

For example, when the disabled girl in the wheelchair wets the bed, Grace notices an irritating feeling taking over her. Annoyed at the idea that she is just wasting her time she says “Nobody gonna sleep here”. Grace appears taken aback by the words she had muttered, whilst the narrator comments “where had these ominous words come from?”.

Shortly after she meets Tom and asks him if he actually threw away the card the gangster gave him. Upon realising he didn’t, she says that was stupid. Her comment strikes us as unusual now, because from the beginning of the film Grace has always displayed an utterly non-judgmental attitude towards eveyone.

Thus, I believe these two scenes represent a pivotal moment in the film, as it heralds Grace’s change from forgiver to executioner. As we will see, this change reflects the move from slave- to master-morality.

Even though Grace is cognizant of the townsfolk immoral behaviour, she doesn’t condemn them but rather believes they are victims of circumstances. As I mentioned earlier, this attitude of putting onself in other people’s shoes as a means to understand their perspective, regardless of how wicked it appears, seems to resonate Stoic practices.

During the conversation with Grace’s father, he calls her arrogant as he is convinced that she is exonerating the townspeople simply on the basis of their ignorance – they are unable to see the moral implications of their actions, and so she pities and forgives them.

This is a very Nietzschean interpretation in my view.

Putting it loosely, Nietzsche believed that pity is a scourge of the mind and there is nothing better to demonstrate that than using Nietzsche’s own words:

“Pity is a waste of feeling, a moral parasite which is injurious to the health, “it cannot possibly be our duty to increase the evil in the world.” If one does good merely out of pity, it is one s self and not one s neighbour that one is succouring. Pity does not depend upon maxims, but upon emotions. The suffering we see infects us; pity is an infection.”

So, to Nietzsche, pity is nothing more than an unconscious way to justify our self-interest. Whenever someone feels pity, Nietzsche would argue that this seemingly moral attitude hides very non-virtuous sentiments, such as arrogance.

According to her father then, Grace isn’t showing pity and forgiveness because she really cares about the townspeople. She is simply attempting to vindicate her inaction by believing that others are below her regarding ethical standards. In other words, her ineptitude to take action and put a stop to the townspeople malevolence is turned into pity for her abusers (an attitude not too dissimilar of slave-morality, more on that below).

At first, Grace dismisses her father’s points, and upholds her belief that we should feel pity and grant forgiveness to the townspeople, despite their corrupted conduct.

However, as she walks around the town once more, she gradually begins to accept that her attitude of self-sacrifice and pity is tantamount to denying the value of her own life. In attempting to live a life in Dogville on the sole basis of virtue, self-sacrifice and forgiveness, Grace realises that she has denied life.

She realises that her passive attitude, her pity and her compassion towards her abusers go to such extremes that it borders complacency in the face of injustice.

As the narrator describes: if Grace had done to others what the townspeople had done to her, she couldn’t possibly justify any of her actions.

This epiphany completely overturns Grace’s values, in what Nietzsche would call “a revaluation of all values”.

Interestingly, at that exact moment, a new light is shone over the town. Remember the first light that welcomed the arrival of Grace the Stoic, full of love, mercy, justice and compassion for the town and its residents?

Well, this is a different light.

As the narrator points out, the light that had once shined so merciful over the town, is now penetrating every flaw in the people. The light metaphorically represents Grace’s change from forgiver to executioner.

As I will describe below, this new light could be construed as the the light of master-morality, the light announcing the arrival of the Übermensch.

In other words, this new light represents her realisation of the futility of her old values and mental structures; the moment when she begins to see beyond false illusions of mercy, pity and forgiveness; the moment when the old Grace can finally be surpassed.

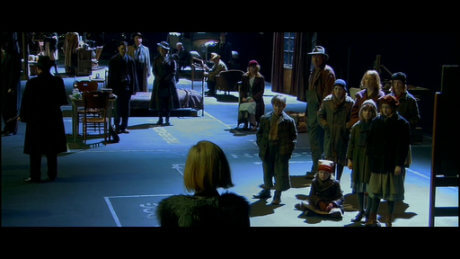

Grace’s methamorphosis comes with the realisation that this town represents an obstacle that must be eradicated, in order to not cause harm to anyone else. Grace thinks that wiping out the town is doing humanity a favour, a chance for the emergence of the Übermensch.

With this new Grace, we see Nietzsche’s “will to power” idea materialising. Remember, “will to power” is not necessarily a will to dominate others (although oftentimes it can be), but rather to assert oneself, make ourselves unique and different.

There is an interesting play with the word “power” in the film. Grace asks her father when would she be given power, at which her father replies, right away. I believe power here refers to something more transcendental: power in the sense of dominion over your own ideals, the way Nietzsche encouraged us to think.

Graces drastic change in her moral views also reminds me of the duality of slave/master morality that Nietzsche proposed.

Prior to the arrival of her father, Grace is evincing a prototypical “slave-morality”, in the sense that given her impotence in acting with strength to fight off abuse, she recoils into a position of submission, and justifies this position by calling the others weak of mind.

Nietzsche insisted that followers of slave-morality will turn a situation of not being able to take revenge into forgiveness – exactly the kind of mindset Grace appears to be demonstrating.

After the conversation with her father, Grace seems to adopt a master-morality. She decides to take an active stance by ordering the killings and burning down the entire town. She is guided by her instincts, by her desires, by her ideals of what is good, what benefits humanity – what Nietzsche would call a true master.

To her mind, Dogville is pernicious and must be sacrificed for the greater good. Out of all residents, only Moses, the dog, is left unscathed from Grace’s application of her renewed morality.

What would Nietzsche say about that?

If you haven’t noticed already, I really revel in good philosophical discussions. Dogville has certainly made an indelible impression on me with that fateful exchange of moral views between Grace and her father.

In fact, I’d go as far as saying that all the clues you need for grasping the meaning of the film are contained within the last 20 minutes or so, during the time that conversation takes place.

As I discussed at great length above, Grace’s radical transformation from forgiver to executioner can be explained by the antagonistic philosophies of Stoicism and Nietzsche, respectively. In short, Grace’s Stoic moral and ethical values of forgiveness, compassion, justice and virtue, were simply ill-suited in a town such as Dogville, whose devious residents were quick to exploit Grace’s kindness. As Grace herself realised, their vicious behaviour couldn’t possibly be vindicated, and for humanity to evolve, a newly forged morality had to be born: a master-morality.

While the new Grace shows no mercy whatsoever (she orders the killing of every single resident, including the children), we cannot but feel that she does not enjoy this “power”. Her demeanor during the destruction of the town is suggestive that she only did what she did because she believed it to be what was most beneficial to humanity, not because she enjoyed it. As Nietzsche would have argued, oppression and sacrifice are sometimes required in order to bring humanity forward.

Grace followed Nietzsche’s thought to the letter.

Both classical Stoicism and Nietzsche’s original philosophical ideas were formulated at a time when religion had a much firmer position in the society.

With most governments now turning to science when passing new legislation (the current pandemic being a perfect example of that), Nietzsche’s idea of the “Death of God” is considered by most scholars outdated, as it pretty much already occurred (at least in the Western world).

Likewise, it is difficult to imagine how anyone would fit in in our 21st century society, following a lifestyle that is purely based on classical Stoic values.

Having said that, both currents of philosophy have certainly evolved to meet modern demands.

Current practitioners of Stoicism, for example, are adapting their ideas to several branches of Psychology; for example, some of their teachings have now been incorporated in many cognitive behavioural therapies.

For my analysis of Dogville, I remained mostly faithful to the original teachings – call me old-fashion :)!

See you in the next article!

Books

Robertson, Donald. Stoicism and the Art of Happiness. Teach Yourself.

Llácer, Toni. Nietzsche – El superhombre y la voluntad de poder.

Youtube

Leave a comment

Add Your Recommendations

Popular Tags